London, 21 October 2014:

The works of two Libyan authors imprisoned for . . .[restrict]ten years under the Qaddafi regime are featured in a collection of short stories focused on prison writing in the Arab world.

Stories in translation by Ahmed Al-Faitouri and Guima Bukleb, who were both held between 1978-1988, are in Banipal 50 – the 50th anniversary edition of the regular publication – a magazine of modern Arab literature.

“We are proud to celebrate Banipal 50 with testimonies and texts from authors who are now some of the most renowned and respected of Arab authors, writes Banipal co-founder Margaret Obank in the introduction. “Their lives and struggles are a testimony itself to the intrinsic need of human beings for tolerance, free expression and compassion.”

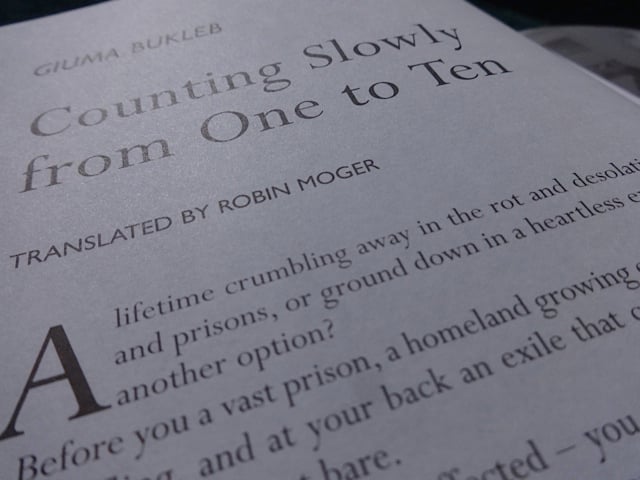

The first story in the collection is by Libyan author Giuma Bukleb. Entitled Counting Slowly from One to Ten, the seven-page story is a moving glimpse into one man’s experience of the changes experienced during a process of counting down the years he was held as a political prisoner under the regime of former dictator Muammar Qaddafi.

The story reads like a prose poem as it charts the ebb and flow of the author’s feelings, during which he repeatedly asks himself, “Is political prison a destiny or a curse?” Experiences range from “the daily struggle against solitude” and the learning of a new language – where educated men learn “how to spit and twist the words of the prison courtyards’ cant, a language nether written nor read,” in the first year, to the second year when “sleeplessness intensifies.”

The story offers readers a rare glimpse into how the mind might process a decade of incarceration, both the world inside and outside the prison walls. “In the fourth year, weariness weakens you. You sleep and the world continues to turn, with you and without you,” Bukleb writes. “There is a land that rises each morning at its appointed time without you. There is a horizon that glows in the distance like a star, then passes away, and you remain alone, wracked with the brutality of solitude.”

There are also moments of illumination, or of a sudden focus on physical well-being: “In the fifth year, you seriously consider giving up smoking and taking better care of your health and heart. The skin hardens but the soul grows fine and clear.”

At the end of the story, the speaker is released. “You smoke without a pause, drink numberless cups of coffee and spend the night open-eyed in disbelief,” he writes. The next day, however, he is paraded with his family in front of TV cameras and forced to “proffer sincerest thanks to those who locked you up for ten years without a crime being committed.”

The year of release also briefly charts the author’s attempts to readjust to a life of which he missed a decade, describing it as “another exile, another prison, another solitude.” Evoking how someone who has passed a decade in prison will never be completely free of the experience, he depicts it in the gentler terms of a constant companion, even an unwanted one.

“You might decide to travel, to start a new and different life; you might strap your bags shut and go away. But prison will travel with you in your suitcase, will settle down beside you in the warmth of your bed, wherever and whenever you go.”

With a reminder of the pain that prison terms inflict on family members left on the outside, Ahmed Al-Faitouri’s story, The Moment the Cell Door Opened, is prefigured by a moving dedication, to his ailing mother, and his father “who died of heartache”. He adds that it is also “for all the mothers and fathers of my unnamed comrades”.

Faitouri, who served ten years in three jails – Al-Jadidah, Al-Hissan Al-Aswad and Abu Salim prisons – describes the day when a group of inmates, the ‘journalism group,’ were informed of their forthcoming release.

The 12 men, including Bukleb, had been given death sentences, reduced to life imprisonment, “for affiliation to the Marxist-Leninist party, seeking to overthrow the government”.

The Moment the Cell Door Opened offers a glimpse into the daily life of these prisoners, from the proliferation of cockroaches to how fellow inmate Ramadan al-Maqssabi pushed pieces of broken mirror beneath the cell door to try and find out what was happening in quiet moments. “While, at first, our spirits soared on a wing of hope, fears subsequently dragged them to the ground,” he writes.

He reveals the camaraderie between prisoners. “In the section of those inmates sentenced to death or life imprisonment there was always a deafening silence. Through a hole in the wall – I found it because ofd the patchwork construction of the prison walls – we started written and verbal exchanges between the cells.”

Faitouri also beautifully illustrates how some of the prisoners held on to their “creative intellect” by creating al-Nawafir (Fountains) magazine which, he said: “We had published in Abu Salim Prison, and whose issues were written on Satin cigarette papers.” They also wrote several books, including a study of Arabic poetry entitled The Debate of the Chain and the Rose and The Reasonable and the Absurd in the Arab Mind – to which, he says, many inmates had contributed.

Faitouri and fellow inmate Idris al-Mismari were unsure what to do with these books when they were summoned by prison officials and told to take their possessions. They were torn between taking the fruits of their labours into the outside world or leaving them inside, for their comrades who were not being released.

“The guard was insisting we go, and we were already eager, so we left the question hanging,” he writes. “And, just as the freedom we so desired had subdued the zeal that joined us together, what was happening now usurped all that had happened before. We wept silently.”

On the day of their release, Faitouri said, Qaddafi gave a speech, “repeating lines from the Libyan poet Mohammad al-Fayturi who, driving a bulldozer, had destroyed the prison wall: ‘Twilight came, and neither the prison nor the guard remains.’ For this reason, we later designated our group ‘Twilight’”.

Bukleb told the Libya Herald that he was delighted his story was selected for inclusion in Banipal 50. “I never thought that story would be translated so it is particularly nice to see that,” he said, adding that he thought it was a very good translation.

“The world our feature writers endured as prisoners has gone, forever. Young readers and writers might not recognise the world they write about,” Obank says. “It seems like another world, hard to understand, where religious fundamentalists and bigots of all persuasions are in ascendence, dictatorships and unelected bureaucracies are still in control, and whistleblowers defending basic human rights are on the run.” She adds, however, that the thought-provoking texts by authors from Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Palestine and Syria as well as Libya, are a reminder of the struggle that continues today to defend the right to free expression, tolerance and social justice.

Banipal 50 includes ten short stories and excerpts from longer works detailing prison experiences. It also opens with a series of beautiful love poems about Syria written by Syrian-Kurdish poet Marwan Ali. [/restrict]