By Chris Stephen.

Tunis, 21 July 2016:

Voltaire would be pleased. Enshrined in Libya’s draft constitution, finally finished and due to go to a national referendum at some point in the future, is the separation of powers doctrine coined by the French philosopher. The doctrine is standard fare in democratic constitutions across the world. The draft Libyan constitution is in fact so standard that the wonder is it took so long to produce, with the Constitutional Assembly elected back in February 2014.

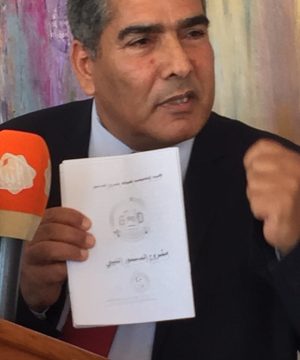

Libya’s turbulence has been one factor another has been divisions in the assembly that saw the chairman, Ali Tarhouni removed, and members split, some heading to Oman for deliberations while others remained at its its Beida headquarters.

Yet from turbulence has come a document containing a power structure recognisable from many of the world’s constitutions. It is, though, for Libyans to choose if this is the constitution they want. Every constitution is a compromise and Libyans themselves will need to decide on this particular framework. It is important to note that what follows is an assessment of the main points of the proposed constitution and that it is based on a review of the English language translation of the draft, while the authoritative draft is the Arabic language version. It is a review, not a definitive legal guide.

Libya

The draft sets out that the country is a unitary state, named the Libyan Republic with Arabic as the official language and Islam as its sole religion.

Executive Branch

At the top is a directly elected president, normally serving a maximum of two five-year terms, with the role of choosing a prime minister and government, endorsing laws, commanding the armed forces and acting as head of state. He, or she, is the apex of executive power. The government prepares an annual budget each September, but the legislature must endorse it. However, the first two elected presidents will only be able to serve a single term in office. The president can declare a state of emergency or war, using emergency powers, but the legislature, the Shoura Council, has the right to cancel it after three days. Martial law can be declared by the president only if also approved by the Shoura Council.

Legislative Branch

Legislative power is contained in the Shoura Council, consisting of two parliaments, a lower House of Representatives and an upper Senate. The HOR has primary responsibly for drafting laws, but both chambers can submit laws and both need to approve them. One of the few ambiguities in this document of 221 articles is that while the Senate is set at 72 members, the HOR membership is stated only as “a number” of MPs.

The Shoura Council also chooses the heads of key independent institutions including the Central Bank of Libya, and, although it is not specifically stated, presumably the National Oil Corporation.

Judicial Branch

The HOR nominates and the Senate confirms heads of the judicial branches of government, including the Constitutional Court, with the courts and prosecution system managed by a Higher Judicial Council tasked with being independent from both executive and legislature.

Qualifications for office

Candidates for the presidency, government and Shoura Council cannot be dual citizens and posts are open to men and women. One potential controversy rests in the age limits set out. Minimum ages for election are 45 for membership of the Constitutional Court, 40 for president and Senate, 35 for Higher Judicial Council and prime minister and 25 for the HOR, while the voting age remains at 18.

In addition, the president must have been resident in Libya for ten years, which, for the time being, will rule out those who were in exile before the 2011 revolution. And if they were in the army or security services, presidential candidates must have quit at least a year before standing for office.

Islam

The article regarding Islam bears quoting in full: “Islam shall be the religion of the State, and Islamic Sharia shall be the source of legislation in accordance with the recognised sects and interpretations without being bound to any of its particular jurisprudential opinions in matters of interpretation.”

This paragraph appears to confirm that Islam is safeguarded as the official religion, with all office holders obliged to be of the Muslim faith. Interpretations of whether this article guarantees the central place of Islam in Libya’s governance are likely to provoke debate. Some opinions have called for the phrase to be “sole source of legislation” while others have called for it to be “a source of legislation.” Supporters will say that the phrasing of this article puts the task of specific interpretation of whether laws comply with the faith into the hands of politicians and judges, while critics will say the phrasing is too ambiguous.

Guidance on Islamic teachings is provided by a 15-member Sharia Research Council. Members are appointed by the Shoura Council for terms of six years, renewable once. The SRC issues advisory opinions on all matters, while also having the right to “Issue individual fatwas on beliefs, acts of worship, and personal transactions.”

Devolution

The thorny question of devolution is also addressed. Regional and city autonomy is a perennial theme in Libya and the constitution says there will be directly elected governates and municipal councils with the right to pass local laws and raise taxes. It is, however, left to the legislature to decide the structure and scope of these bodies.

Central Bank and National Oil Corporation

The legislature also has the power to make contracts and agreements for natural resources. While a National Oil Corporation is not mentioned in the constitution, it looks likely to enjoy limited independence, its key actions depending on control from Libya’s elected representatives. The central bank is granted “autonomy” but must act “within the public policy of the state” which sets its parameters.

As such, the constitution specifies a form of independence, at least from undue interference, for both bank and NOC, while giving the legislature the power to set each organisation’s parameters.

Language

Arabic is the sole official language, but the constitution also calls for protection of the right to speak the Amazigh, Tuareg and Tebu languages.

Rights and Freedoms

Men and women are granted equal rights. Most of the first 71 articles detail other rights including equality before the law, due process, movement, transparency, state healthcare, free expression, disability care and free assembly. By law women will get a minimum of 25 percent of HOR seats, and seats on local councils, although there is no minimum set for the Senate. This guarantee of female representation lasts for the first twelve years, or three election cycles.

Transitional arrangements.

Elections for president and Shoura Council must be within 180 days of the constitution being approved by referendum, and the election law must be fixed within the 90 days by the current House of Representatives, based in Tobruk, together with the Higher National Election Commission.

What happens next

The House of Representatives presently in Tobruk is now tasked with preparing a law for a national referendum, with Libya’s voters getting the choice of whether to accept or reject it. Neither the HOR nor other bodies has the right to change the draft. If it is rejected by referendum, the constitutional assembly is tasked with producing a new version, again to be judged in a referendum.