By Sami Zaptia.

London, 14 June 2017:

A UN report has concluded that ‘‘a variety of sources of funding are available to (Libyan) armed groups’’, assessing that there are ‘‘four important sources of funding: fuel smuggling, trafficking in persons, interference with institutions and the local arms trade. Previous findings on income from other criminal activities and State financing remain relevant’’, the report said.

The report names Zawia’s coast guard as active participants in fuel smuggling and names a Zawia militia and its leaders. It also names people smugglers and details the involvement of sophisticated international cross-border smuggling and finance rings in the smuggling process.

With regards to arms smuggling the report says weapons materiel offered includes heavier and more sophisticated systems. It gives the example of a functioning Milan anti-tank system including four missiles being available for US$ 9,000. In some cases, it adds, fighters and arms are on offer together as a package.

It concludes that smuggling occurs virtually uncontested because of the lack of reliable security forces.

The conclusions were made by the 299-page UN Libya Experts Panel report 2017 released in the first week of June.

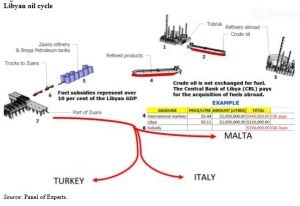

In its assessment of fuel smuggling by sea as a source of income for Libyan militias, the report stated that ‘‘the National Oil Corporation decided to work actively against fuel smuggling. Brega Petroleum, a subsidiary of the Corporation, established an “Oil and Oil Derivatives Oversight Committee” to investigate the problem. Its findings led the Corporation to take action against some companies and individuals in early 2017’’.

‘‘In fact, the Corporation has accused the Petroleum Facilities Guard in the refinery in Zawiya of participating in fuel smuggling operations. The Panel continues to observe vessels showing suspicious navigational patterns in the vicinity of the coastal town of Zuwara. Individuals and companies mentioned in previous reports are still. In 2016, the Libyan coastguard impounded several ships in the same area in incidents related to fuel smuggling’’.

The UN report highlighted the dysfunctionality of the Libyan state and its institutions such as the Libyan Coastguard which is receiving training and equipment from the international community. ‘‘Criminal networks tip off the coastguard to prevent rival gangs from carrying out successful smuggling operations. The coastguard in Zawia is also involved in the smuggling business’’, the UN reported.

The report also noted that ‘‘the Economy, Trade and Investment Committee of the House of Representatives issued a statement on 17 July 2016, addressed to the Maltese authorities, recalling that subsidized products are not eligible for export. On 25 October 2016, the western National Oil Corporation addressed a letter to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs requesting it to send reminders to neighbouring countries that the Corporation is the sole entity authorized by law to import or export crude oil and its derivatives’’.

‘‘The leader of the Petroleum Facilities Guard in Zawia, Mohamed Koshlaf (Kishlaf), also known as Kasib or Gsab, is involved in the procurement of fuel for smugglers. He also commands the so-called militia Nasr. His brother, Walid Koshlaf, also known as Walid al-Hadi al-Arbi Koshlaf, runs the financial side of the business. The head of the coastguard in Zawia, Abd al-Rahman Milad (alias Bija), is an important collaborator of Koshlaf in the fuel business’’.

‘‘Another significant smuggler operating from Zawiya is Ibrahim Hneish, who leads his own armed group. On the other side of the fuel business, brokering companies reach out to vessel owners through established channels to buy fuel from Libya. The western National Oil Corporation, when made aware of those offers, contacted the companies involved to remind them of the illegal nature of the proposed deals’’.

‘‘Fuel smugglers provide the captains of the vessels with official-looking documents. Some of them, when contacted after the impounding of one of their vessels, refer to such documents to claim the legality of the shipment’’.

Commenting on attempts by foreign ships to smuggle Libyan fuel, the report concluded that ‘‘fuel smuggling can quickly expand when no credible deterrence exists’’. The report says that ‘‘the eastern National Oil Corporation has denied its involvement’’ in one smuggling case, ‘‘although at least one member of its board seems to have been involved. It might indicate internal divisions within the board, resulting in unilateral actions being taken by some of its members’’.

Reporting on fuel smuggling by land, the report says that ‘‘fuel is transported from Zawia to Zuwara, Ajaylat, Riqdalin and Jumayl and then smuggled by land onward to Tunisia. The “Oil and Oil Derivatives Oversight Committee” carried out a field visit to Ras Ajdir and Zuwara in July 2016. Its report was delivered to the Presidency Council through the National Oil Corporation and addresses smuggling by land and sea. This trade has also become a concern for the Tunisian authorities’’.

Although with regards to fuel smuggling by land, the report assesses that ‘‘recently, it was reported that measures had been taken to reduce illegal flows’’.

On migrant smuggling and trafficking in persons the report says that ‘‘Migrant smuggling and trafficking in persons is integrated with other smuggling activities, such as smuggling of arms, drugs and gold. Armed groups actively participate in the smuggling or take a cut of the profits. Smuggling occurs virtually uncontested because of the lack of reliable security forces’’.

With regards to migrant smuggling in Western Libya, the UN report states that ‘‘arriving from Agadez in the Niger, migrants are gathered in warehouses located in Qatrun, Awbari, Sabha and Murzuq, where several groups make a profit from facilitation’’.

‘‘Tebu and Tuareg smugglers “facilitate” migrant crossings of the southern border. Tebu leaders, such as Adamu Tchéké and Abu Bakr al-Suqi, collect tolls in cash for travel from the border to Sabha. Tuareg leaders, such as Cherif Aberdine, control the route to Murzuq’’.

‘‘In Sabha, members of the Awlad Suleiman tribe are reportedly organizing the smuggling. From Ghadamis to Bani Walid and Nalut, the Zintanis Mohamed Maatoug and Ali Salek are frequently mentioned as major transporters of migrants (and cannabis)’’.

‘‘On the coast, the main facilitators are based in Zawia, Zuwara and Sabrata. They include the armed group commanders Mohamed Koshlaf and Ahmed Dabbashi (alias Amu). Coastguard commander Abd al-Rahman Milad (alias Bija) collaborates with Koshlaf. The main departure site appears to be Talil Beach, in the resort complex in Sabrata’’.

With regards to people smuggling in Eastern Libya, the UN report says that ‘‘the eastern route is managed by “fixers” from Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia, who identify candidates for departure and handle the finances. Libyans organize transportation within their territory. Migrants who have taken this route systematically report that uniformed men were overseeing their movements’’.

‘‘The coordination in the border region of Kufra is supposedly organized among the Tebus, Zways and elements of the Rapid Support Forces in the Sudan deployed along the border with the Sudan. Up until 2016, most of the migrants were taken from Kufra to Ajdabiya, where they were kept under the authority of the commander of the Petroleum Facilities Guard, Ibrahim Jadhran’’.

‘‘One Eritrean, detained for a year in Ajdabiya, told the Panel that migrants were used by the Petroleum Facilities Guard for demining operations without any military training or protective gear. The Petroleum Facilities Guard finally transferred him to another armed group in Sabrata’’.

‘‘The Panel is investigating a number of bank transfers from relatives of migrants located in Sweden. These deposits are being made to Swedish bank accounts of the migrant smugglers for onward transfers through hawala systems located in the Sudan and in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, where the money is laundered’’.

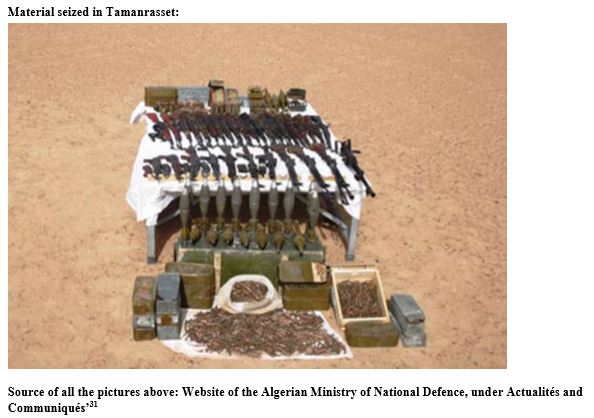

On the issue of financing from local arms trade, the UN Libya Experts panel report says that ‘‘the arms trade within Libya is an important source of income for various armed groups. The Panel received reports of active arms trading at markets in Zintan, Misrata, Ajdabiya and Waw. The materiel offered includes heavier and more sophisticated systems. A functioning Milan anti-tank system including four missiles, for example, is available for $9,000. In some cases, fighters and arms are offered together’’.

‘‘Local arms trading is also organized through virtual markets. The Panel continues to observe weapons being offered for sale on Libyan Facebook sites. The Small Arms Survey has recently highlighted their use by armed groups and their members’’.

‘‘Finally, armed groups are also involved in the business of modifying nonlethal equipment, such as pickup trucks, blank firing guns or ammunition, for military use’’, the report concludes.