By Adam Tarhouni.

Tunis, 21 July 2016:

Libya’s liquidity crisis has commanded headlines and has been on the mind of Libyans for several months. People queue outside banks, while the bank vaults sit empty. Stores lack goods, and people are rushing to get rid of dinars. But what do we know about the causes of this crisis and what can be done to reverse it?

To begin to understand the crisis, we only need to look back five years. While the revolution raged, a similar liquidity crisis gripped the economy. Banks had little cash, goods were scarce and the black market thrived. As a member of the Ministry of Finance under the NTC I remember clearly grappling with the liquidity crisis throughout the Libyan 2011 revolution. Political instability created both of these crises.

The economic system depends on trust, and in 2011 and 2016 political chaos damaged that trust.

In many ways these crises mirror one another. But one critical difference separates the revolution and today. Political instability ignited the crisis during the revolution, and that instability injected huge amounts of risk into the economy. Similarly, political instability started today’s crisis. But, today, rather than risk, it is uncertainty and fear which drive the economy.

Risk and uncertainty differ in subtle ways, but the differences help explain what is happening in the market today, and why this crisis is much more severe.

Risk is normal, and always present. It means we do not know whether we will reach a certain outcome. When faced with risk we estimate the likelihood of the outcome in question, and prices reflect that likelihood. Uncertainty means we do not even know what the outcome is. We cannot estimate or price uncertainty into the market. Uncertainty paralyzes us and fills us with fear.

During the revolution we faced great risk, but we knew the possible outcomes ahead. We knew the revolution would succeed, topple the regime, and liberate the country, or it would fail and we would remain under a dictatorship. People understood the outcomes and the market estimated the risk.

Today, we do not know the outcomes. We cannot know whether we are moving forward or backward because we do not know where we are going. We can still estimate the likelihood of all sorts of different events. But without a clear outcome on the horizon we cannot know if those events move us closer to the end goal.

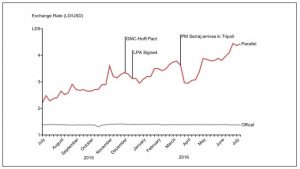

Turn to Libya’s black market to see the effect of uncertainty and fear. Libya’s foreign currency black market shows how uncertainty is eroding the economy. One-dollar had cost 2.2 dinars a year ago. Today it costs more than 5 dinars. Uncertainty and fear have wiped away more than half of the dinar’s value in 12 months.

Certainly, there are sound economic reasons for a black market to exist, and for the dinar’s value to be low. The Central Bank of Libya has limited access to dollars to preserve the country’s dwindling foreign reserves, and the economy is producing a fraction of its former output. Oil production is down to 400,000 barrels a day and the price of oil is less than half of its peak. It’s clear the dinar should be worth less than the 1.38/USD official rate.

But these economic fundamentals only tell part of the story. A year ago a barrel of oil cost $53, compared to $49 today. And Libyan oil production a year ago was 400,000 barrels a day, right where it is today. Yet in that time, the dinar’s value halved, and the banking system plunged into a severe liquidity crisis.

Libya’s economic fundamentals dipped long before the onset of the liquidity crisis and the fall of the dinar. The market has become divorced from the economic fundamentals in the last year. Fear and uncertainty, not logic, drive the market today.

If we know what drives the market, what can we learn from watching the market move? We know the dinar should be lower than the official rate, but we don’t know what rate is appropriate. But if we ignore the level of the dinar, and focus on the trend we have a very good proxy for uncertainty in the country. A fear index.

Of course, many factors influence the black market rate that have nothing to do with uncertainty. But a fear index can be a rough guide to the mood of the country, a comprehensive but imperfect indicator of where we are headed.

We can track major political events using the fear index. In December last year the GNC and HoR signed a pact which suggested a resolution was on the horizon. Two weeks later the Libyan Political Agreement was signed in Morocco. During the month of December while political progress appeared to be happening the value of the dinar rose 12%. When Government of National Accord Prime Minister-elect Serraj arrived in Tripoli at the end of March the value of the dinar shot up by 18%. The bump was sustained for nearly a month before the value plummeted again.

For a brief window after both of these events an end goal flickered into focus and fear subsided. But these gains were short lived and we quickly found ourselves mired in uncertainty once again.

This leads to another key point about uncertainly. Uncertainty is insidious, and if given time it expands. When there are no changes in market forces, most indicators stay stable. But every day that uncertainty persists the fear index grows. With every day that passes our end goal recedes. If things stay as they are, fear grows.

But we escaped this cycle before, so what can we learn from our experience during the revolution? Two things happened simultaneously at the end of the 2011 that pulled the economy back from the brink of collapse. First, with the liberation of Tripoli and death of Qaddafi political stability returned.

Secondly, newly printed Libyan dinars arrived in the banks lessening the cash crisis. Then, as now, we faced an economic crisis with political roots. Progress on both fronts was required to lift us out of the crisis. One without the other would not have been enough.

It is safe to say that we cannot recover from this without political reconciliation and stability. But that does not mean our economic decision makers have the luxury of a wait-and-see approach. Assuming that the liquidity crisis cannot be resolved until stability returns, and oil production resumes: is a recipe for disaster. The Libyan people are suffering and the economy is grinding to a halt. We need decisive action from our leaders on all fronts before it is too late.

Adam Tarhouni is an expert advisor in the fields of economics and finance and a graduate of Stanford University. He has worked as a corporate strategy consultant with Bain & Company as well as a venture capital investor. He was a member of the Libyan Ministry of Finance under the National Transitional Council during Libya’s 2011 revolution.