By Jamal Adel.

Tripoli, 23 June 2014:

With Ramadan looming and the memory of severe power outages last summer, most Libyans are concerned . . .[restrict]about whether or not there will be good electricity this Ramadan. What they do not spend much time thinking about is the dedication of the General Electricity Company of Libya’s lineman who keep the lights on and the air conditioners running.

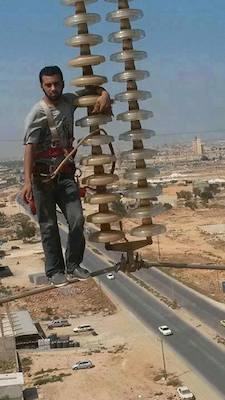

Few realize the dangers that GECOL’s linesmen face, working in extraordinary conditions of severe insecurity and high risk. “GECOL linesmen do repairs and reconnect wires at heights of 45-50 metres,” GECOL maintenance manager in one of the Benghazi offices Abdulmonem Al-Shanti told the Libya Herald.

These are men of true heart and absolute dedication who put their lives in danger so that Libyans can enjoy electricity, yet few realize this.

In the clashes in Benghazi over the past two months, the power supply was disabled early on in the areas of Sidi Faraj, Kuwaifiya and Gwarsha. GECOL engineers managed to do a few quick repairs immediately to restore some power to the areas, followed later by a more thorough fix – this is spite of the threat level of doing work there.

Benghazi’s power stations are crucial not only to the city, but to large parts of the country. The North Benghazi Power Station covers the eastern area but also generates enough power for the station to provide excess electricity to the western part of the country through the national grid.

Speaking of this station, Al-Shanti said that although grid lines were cut in the clashes and production was greatly decreased, the station was still able to keep up with some production. “Luckily, the transformers were mostly intact and experienced no significant damage.”

Al-Shanti described to the Libya Herald the efforts of GECOL’s linesmen to upgrade the grid that connects Gemenis, south of Benghazi, to the Benghazi station. “The power lines in Gemenis were old and the area used to experience rolling power outages. The repairs we made to this part of the grid were extremely difficult. Aside from the heights at which our linesmen had to work, imagine the temperatures of the steel pylons on which they were working!”

When asked how it felt to work as such great heights on the pylons, Al-Shanti admitted to “unimaginable trepidation.”

Speaking of the weather conditions and their effect on the linesmen’s work, Omar Al-Furjani, a field engineer for the pylon maintenance department in the eastern area, told this paper: “Weather conditions affect the work significantly. Repairs are not recommended on windy days because even slight winds could lead to incidents.”

Al-Furjani described climbing a tall pylon: “It was definitely something fearful. The lines normally have anything from 66 to 400 kilovolts of power.”

Al-Furjani has now worked for five consecutive years as a GECOL engineer. “In my five years of work I haven’t had an accident myself, but a friend of mine who received an electric shock in his hand has now left line repairing and become an administrative employee,” he said.

“Usually, in order to do repairs, a large number of safety procedures are followed. However, in some situations where we are having to work quickly, that changes.” He described a harrowing time when they had two days to repair the offline Ajdabiya-Zueitina line. “We had to work close to live lines. Some of the linesmen felt the currents, which are often magnified by wind and humidity. The linesmen and the team on the ground had to communicate by shouting instructions to one another.”

Many linemen view their work as a manifestation of loyalty and patriotism. Abdulsalam Al-Tayash, a GECOL linesmen who repairs high voltage lines,explained: “It is very normal for me to work at heights. To be honest, I feel this is a real manifestation of loyalty to my country and unconditional service to Libyan citizens.

“I haven’t felt fear of working at extreme heights in my 14 years of service working and connecting conductors, though I have felt a bit anxious when strong winds shake the pylons,” he added.

Unmarried, Tayash who lives in Benghazi s raising his younger siblings, has worked in different areas across the country, including Kufra, Sarir and Jalu. Describing the recent work in Benghazi to repair lines in Gwarsha during the fighting, he said that he and his colleagues had worked “very hard, with the fighting around us almost continuous. It was a real danger as we were working to repair lines, sometimes until 8 or 9 in the evening each day.”

Al-Tayash was involved in a work accident in June 2011 in Jalu. “My partner, Mahmoud Juma Al-Badri, died and the fourth and fifth vertebrae of my spine were damaged.”

Not long afterwards he was sent to Misurata to conduct repairs to the Misurata-Zliten line. Speaking of his time there – 1-20 August, during the middle of the revolution – Al-Tayash explained, “The pressure to get the work done was incredibly intense. We had to combat nearly impossible situations and try to provide as much power as possible to our country. The work we achieved was way beyond what we should have been capable of.”

When he arrived at Misrata he started to experience pain in his right leg, possibly an effect of the June accident. “I could not walk,” he stated. “Even today I often feel this pain.”

GECOL linesmen feel that the media is often unjust in its portrayal of GECOL and its linesmen, overlooking their sacrifices and courage.

“The media has not portrayed us well, therefore the people are only concerned with having their lights on and may not fully know the difficulties that we have to face. A number of GECOL heroes’ efforts have gone unnoticed and unaccredited,” he declared. [/restrict]