By Mustafa J. Salem and Hans-Joachim Pachur

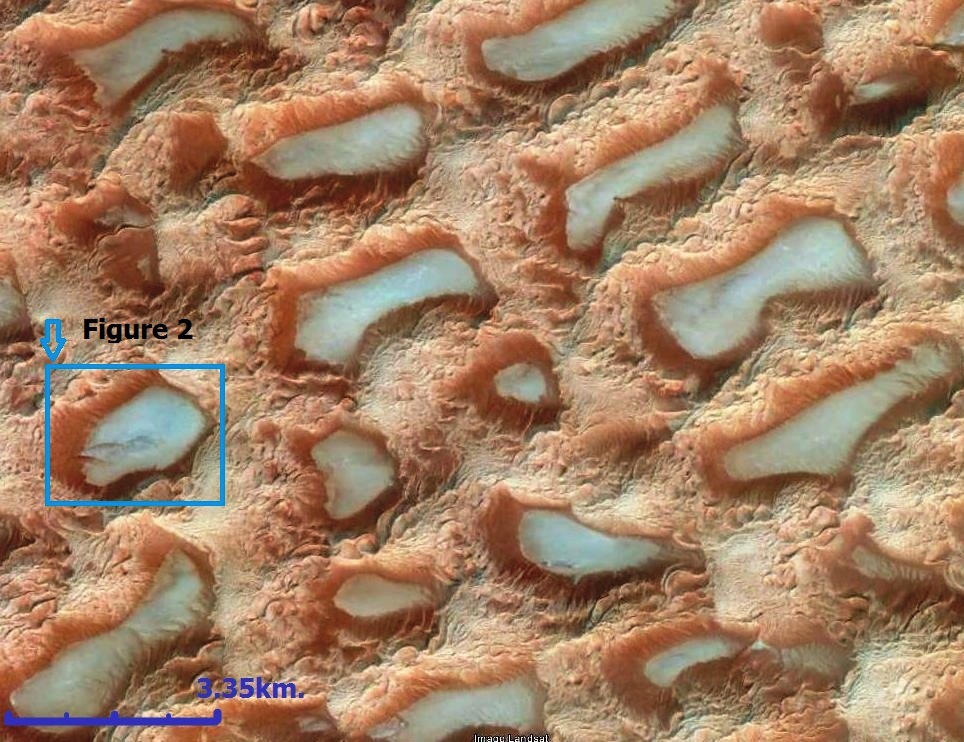

![Figure 2: . . .[restrict]A close-up of one of the numerous dry lakes within the Murzuk Sand Sea. Thanks to Google Earth for the extraordinary three-dimensional details of the various sand dunes. Note the old lake deposits which give good rock exposure at the lowerside of the lake.](http://www.libyaherald.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Figure-2-MSalem.jpg)

When we look at the landscape of the Fezzan region using satellite images or Google Earth, the most striking and dominant type of terrain is the dunes. The area has the most interesting and remarkable dune fields in Libya and probably in North Africa. The two main Sand seas are Idhan Murzuk (Murzuk Sand Sea) and Idhan Obari (Obari Sand Sea).

These two vast sand seas are located in two huge depressions that are surrounded on all sides, except the east, by mountainous terrain of various rock types. From the east there are prominent depressionswhich cannot be missed representing old rivers running toward the east-northeast, toward the Al Haruj Volcanic Field. These old rivers are what are now called Wadi ash Shati, Wadi al Ajaland WadiBarjuj (Figure 3).

The two sand seas cover an area exceeding 125 000 km2. They are separated by the crescent-shaped MessakPlateau which is formed of resistive Mesozoic sandstone beds, which dip away from IdhanAwbari towards Idhan Murzuk (Figure 3). The dunes are mostly longitudinal and barachanoid with tranverse dunes and common star dunes some of which are almost 200 metres high.

Such dune structures form a very complicated landscape which is exceedingly difficult to cross. Corridors between the longitudinal dunes can extend for tens of kilometres unless they are cut by transverse dunes running at right angles to the longitudinal dunes. Between the dunes in these corridors lie hundreds of dry palaeolakes each of which extends for a few kilometers in all directions (Figures 1,2, 4, 5 and 10).

Historical Background

Dunes have existed at Idhan Murzuk and Idhan Owbari since at least the Pleistocene epoch. Acheulian and Aterian artefacts exist within the corridors of these dunes around the edges of the old lakes. These lakes were interspersed at a distance of approximately six kilometers, with a dimension of up to 3 x 12 kilometres and a water depth of upto 20 metres. It is thought that the water quality ranged from fresh to brackish.

Dating of organic material, pottery and bones of vertebrates from these lakes indicate that the humid phase in the Idhan Murzuk area lasted from more than 8,100 years ago to about 5,300 years ago (H.-J.Pachur, 2012).

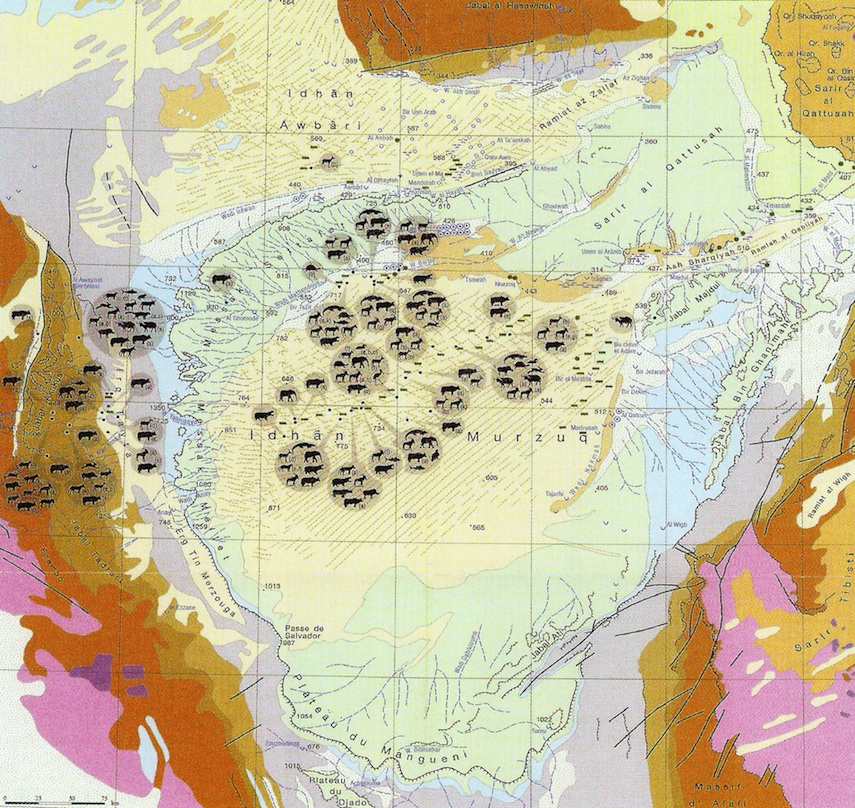

Based on the types of mammals in the area at the time, it can be postulated that during that time the dunes had a grassland and open woodland vegetation. This is associated with fresh-brackish water lakes and salty earth, with swamps and flooded grassland suitable for hippopotamus, buffalo, waterbuck, korrigum and domestic cattle (Figure 6).

Bones of some species embedded in dated lake sediments have been reported (H.-J. Pachur, 2012). Similar fauna were painted and engraved in the nearby mountainous areas of Messak and Akakus (Figure 3). The frequent occurrence of tethering stones used during hunting indicates that the area was well suited to cattle rearing and hunting. It is believed that the Idhan Murzuk area had a much higher rainfall at that time, possibly as high as 400 millimetres per annum (H.-J.Pachur,2012).

Idhan Murzuk and Idhan Obari as tourist attractions

Just over two decades ago, crossing either Idhan Obari or Idhan Murzuk was a risky undertaking for any tourist. At the time only the local people (mostly Tuareg) knew the passages and therefore how to reach the areas deep within these huge sand fields.

However, with the advent of GPS technology and satellite phones and then high resolution satellite images, it became quite feasible to navigate through these dunes without the risk of being lost in the desert.

The arrival of the oil companies in these areas with their huge facilities made the adventure even easier. Most of the Tuareg who knew the area very well have become guides to assist in crossing these dunes. The Murzuk Sand Sea has since been crossed many times with tracks and pictures of tourists all over the area.

The introduction of lighter vehicles, especially motorcycles and quad bikes, has made the area even more accessible to tourists, especially to those who enjoy off-road driving and motorcycling with complete and unlimited freedom.

In the last two decades a few international rallies have also been organised which have helped popularise these areas for adventure off-road driving (Figures 7 and 8). The dune areas are attractive not only to adventure drivers but also to people interested in archaeology as these areas, up until two decades ago, were very rich in prehistoric archaeological remains dating back thousands of years.

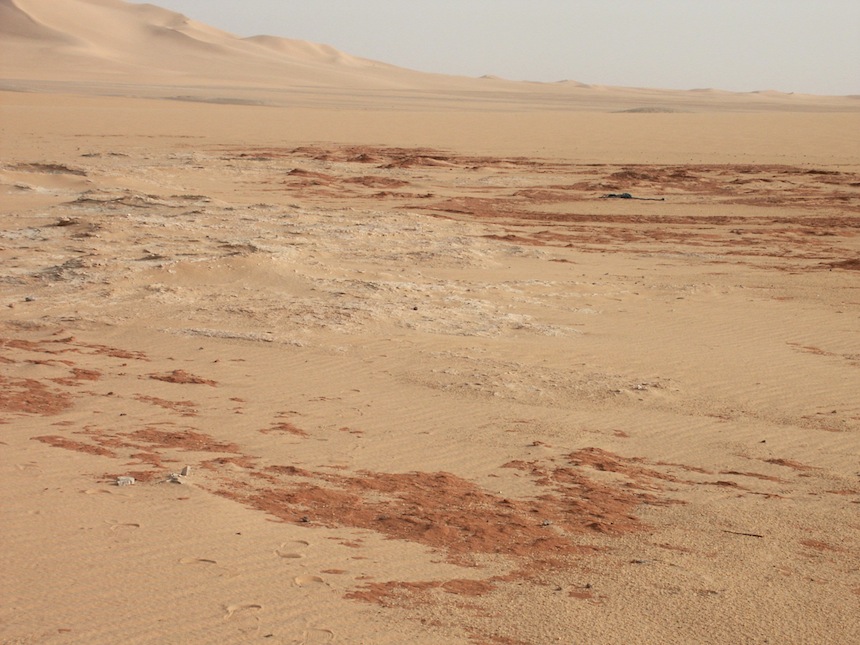

Impacts of Tourism

Uncontrolled off-road driving through the dunes by tourists has a huge impact on the surface especially in the corridors where all the palaeo-lakes are situated. The surface of these areas is very fragile and contains the remains of historic fossils as well as archaeological remains which are subject to displacement, theft and destruction by unregulated driving. The use of motorbikes, quads and a large number of vehicles such as those in the rallies has a tremendously deleterious impact on the surface, archaeology and habitats of the area.These impacts will be obvious scars for many decades. Compare the tyre tracks from WWII that are still visible on areas of desert pavement and will be for many years to come.

Impact of Oil Exploration

Oil companies are required by law to conduct Environmental Baseline and Impact Assessments prior to any exploration or exploitation of hydrocarbons anywhere in Libya. All operating companies have their own HSE standards and requirements which in theory coincide with the environmental requirements of the country.

However, as a result of the oil activities in the desert, we still see lots of negative impacts on the environment, especially on the surface landscape. Among these impacts we can list:

- Random driving and the impact on the surface topography;

- Disturbance to the archaeological remains including some dislocation, accidental destruction and the removal of artefacts as souvenirs;

- Use of heavy machines such as bulldozers and rollers to open tracks and access lines for seismic activities. These tracks provide new access to remote areas whichhad been off-limits to any vehicles prior to their opening;

- Civil work associated with the oil industry such as pipelines, gas-oil separation installations, power plants, offices, residential areas, airports, etc.;

- Disturbance to the rare fauna due to the large number of people, the noise, the movement of vehicles and sometimes opportunistic hunting;

- Solid and liquid rubbish littered around the base camps and oil installation bases;

- Pollution by associated water sometimes leading to nitrate enrichment of groundwaters, hydrocarbon spills, and fumes;

- Use of some of the precious water for oil production.

Most of these impacts could be avoided, rectified or at least minimized if the companies operating in the desert are determined and committedto respecting the unique landscape and putting environmental issues and local sustainabilityat the very top of their priority lists (Figure 9).

Urgent need for control

Idhan Murzuk and Idhan Obari are not the only fragile heritage areas that need urgent attention from the authorities in Libya. Almost all the natural and human heritage areas need protection including the ones that were recognised by UNESCO as World Heritage archaeological sites.

Negative impacts are affecting all the heritage sites in Libya in various ways. Some through deliberate vandalism, others through a lack of adequate legislation and/or weak enforcement while others are due to ineffectual management, negligence on the part of the authorities and lack of public awareness.

Whatever the reasons, the results are always the same – further damage to Libya’s valuable and irreplaceable history. The Idhan Murzuk area has very little grazing land, up until now has been devoid of any residents and, except in the western part, has not been affected by oil exploration activities. This area, with its wealth of prehistoric remains and interesting geological history is yet to be studied by experts.It should be maintained as an area strictly prohibited to any off-road driving adventurer or archaeology enthusiast.

Perhaps a small area on the fringe of the sand sea could be allocated for driving through for such sports while the rest of the area should be restricted and accessible only to authorised researchers or personnel. Officially sanctioned safari trips could be arranged to controlled areas for small groups using camels.

Idhan Murzuk should be designated a national park with all appropriate restrictions. It should have a management system that is regularly revised and updated and well trained and motivated staff should be employed to supervise and control access to the area.

The Namib Sand Sea in Namibia is a good example of such an arrangement.

As for Idhan Obari which has already been invaded by the oil industry as well as by locals, control measures should focus initially on the western side which so far has not engendered any industrial interest, while the eastern side should be managed to reduce future impacts as much as possible and mitigate the damage so far.

Unless such controls and appropriate legislation and management are applied soon, these fragile areas will deteriorate fast and the damage will be irreparable.

[/restrict]