By Mustafa J. Salem.

Tripoli, 2 March, 2016:

Jewellery has for an extremely long time played an important role in the lives of . . .[restrict]Libyan women.

Parents make sure long in advance that their daughters have enough jewellery for the marriage they will make. Jewellery is also part of the bridal dowry from future husbands – to such an extent that, normally, no jewellery given means no marriage. Jewellery confers social status and represent financial stability. It provides a means of security for a woman in case of divorce, widowhood or other financial difficulties even while still married.

The most remarkable features of Libyan jewellery are the very different of styles and the artistic skills on show in the pieces that Libyan women wear in copious amounts. Most women wear some of their jewellery on a daily basis. However, their most prestigious head ornaments, large necklaces and brooches are kept for such important events as community festivals or weddings.

Styles, motifs and techniques

Throughout history, Libyan jewellery has consisted of gold, silver and semi-precious stones, all created in intricate handwork by trained craftsmen. It is not uncommon either to see similarities in style with jewellery produced by neighbouring lands, especially Egypt and southern Tunisia.

Inevitably, older styles of jewellery resulted from contact with Egypt, Tunisia and other Mediterranean cultures. These were used by local Arab, Amazigh and Jewish craftsmen who merged them with their own traditional styles. As a result there are similarities in style, materials, tools and techniques used across North Africa.

As elsewhere in the Mediterranean world, the materials, decorative motifs and shapes carry inherent symbolic meanings – in some cases, seeking protection against jealousy, evil and misfortune.

There are motifs such as hands (khmesa), birds (usfur), fish (al-hut) and stars and moon (nejma wa hilal). Others take their shapes from the animal and plant world such as snakes, salamanders, pine trees and vines. These were thought to serve as protections against evil spirits and jealousy.

Spirals, zigzag lines, triangular shapes, and eye shapes are also common, all looking to provide protection as well.

Jewellery in Libya and North Africa in general often uses different techniques including filigree, enamel, niello (the black mixture of copper, silver and lead sulphides used as an inlay), piercing and engraving. Libyan silver is particularly well known for its engravings and filigree while other areas of North Africa especially Algeria and Morocco are reputed for their well-detailed enamel jewellery in black, blue, green and yellow and with semi-precious colourful stones (Figures 1 and 2).

Tripoli as a centre for jewellery craftsmanship

Tripoli, with a wealth of craftsmen, was historically a centre of trade not only for different areas of Libya, was also between Mediterranean countries and central Africa.

From Tripoli, two important caravan routes departed south. One went to Ghadames, passing through Jebel Nafusa, then from Ghadames to Ghat and further south to Agadez in Niger and as far south as Kano in Nigeria. The other went to Socna, Murzuk and on to Bilma in Niger, and then to Borno.

Inevitably, as an important regional trading centre, Tripoli was crowded with workshops crafting and selling various types of jewellery, both for the local market as well as for export to those places it traded with, especially in North Africa.

Elsewhere, in smaller communities such as those in the Jebal Nafusa, there were several craftsman’s workshops producing semi-precious objects for the rural communities outside main cities. But it was (and still is) in Tripoli and Benghazi, where silver and gold were officially hallmarked.

Elena Schenone Alberini, in her book Libyan Jewellery: A Journey Through Symbols (1998), notes that in 1902, Paul Eudel, the French collector and author of a number of books on silverware, including silverware in North Africa, stated that the heart of the trade in Tripoli was around the iconic Marcus Aurelius arch. The suq of the silversmiths and goldsmiths, Suq Siagha Al-Dab wa’l Fudha, contained what was described as “wonderful craftsmen, working with the finest and most intricate art on gold and silver”. Today, the gold market is at the other end of the Old City.

The goldsmiths and silversmiths learned their skills from professional master smiths at an early age as apprentices and then, as they became masters, passed them on to a new generation. Usually young boys apprenticed themselves to male relatives, learning to make jewellery through the long process of observation and practice.

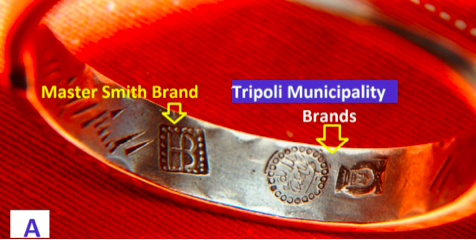

The master smiths were organised in an arts-and-crafts guild and one member would be chosen to act as the official guild master – the Amin Al-Suq. Elected from among the most respected members belonging to the guild, he acted as a representative of the master smiths and, when necessary, negotiated on their behalf with the local authorities, dealing with any problems concerning the practice of the silversmiths and goldsmiths. He also guaranteed the rights of the buyers and the quality of silver or gold they bought. The object was to prevent theft or counterfeiting. As a part of his job, he would brand the crafted objects with his initials before it was branded again by the local authorities ahead of it being sold (Figure 3).

The Amin Al-Suq is still there but his office and the guild are not functioning as they used to.

Abdelghanei Shakshouki is one of Tripoli’s well-known silversmiths who, along with his brothers, learned their profession and inherited their business from their late father Mabrouk Shakshouki. He was the Amin Al-Suq for several years back in the 1950s and 60s. His own work as well as his brand initials on the silver that was crafted during his time as Amin are still very common in the market today. The Shakshouki family workshop is still open in the present Suq Al-Siagha where family members are still crafting traditional-style silver as well as selling old and new products (Figures 4 and 5).

Another talented master smith who is also still active in silver and gold crafting is Khaled Zlitni,who says that he too learned the profession from Mabrouk Shakshouki (Figure 5). Zlitni says he is not as busy as he once was because demand for traditional silver work has declined. However, he and his son still meet his clients’ demands for certain traditional styles and also craft high-quality gold items in the more modern styles now wanted (Figures 5 and 8).

A distinguished and talented craftsman who made a considerable contribution to training and design in Tripoli in first half of the last century was Italian goldsmith Guido Angelini. Born in 1908 in Bellaria near Rimini and originally a mechanic by profession, he moved to Tripoli in 1935 to be a trainer in the then newly founded Goldsmith’s and Silversmith’s School (Scuola di Orafi e Argentieri). Several young Libyan craftsmen learned their skills there under Angelini who not only trained them to be talented master smiths,but also helped them to invent their own tools and to use rolling-mills in their work on silver. Mabrouk Shakshouki was one of them. Elena Schenone Alberini describes the talents of Angelini in her book: “After long years of accurate and painstaking study, he reached a recognisable style, linking his creation to the needs of modern society. Linear and geometric motifs, inspired by unique, ancient motifs of Saharan jewellery decorated necklaces, rings and bracelets adorned with beading and filigree techniques” (Figure 6).

He created an unique style of jewellery and silverwork, blending Art Deco with local Arab and Amazigh designs which others followed and which some now refer to as the “Tripoli School”. He remained in Tripoli under expelled by Qaddafi in 1970 along with the rest of the Italian community.

Perhaps the most effective training centre in Tripoli (and the official one) was the Madrasset Al-Funun wa Al-Sanaiya Al-Islamiya, which was founded towards the end of the Ottoman period and which continued its function of training young people in various handcrafts including metalwork till very recently. Many professional goldsmiths and silversmiths as well as other traditional craftsmen learned their skills in this school, some of them still active today.

Unfortunately, the activities of this school were stopped by the former regime and the historical building in 24 December Street is now derelict and deteriorating (Figure 7).

Today, there are some younger silversmiths working in Tripoli but there are fewer and fewer wanting to learn the skills, saying that the work is time-consuming, does not pay enough for all that is involved and is not much in demand anyway.

Instead, in the gold market in Tripoli’s Old City and in jewellery shops, there are more modern-style pieces on show. Some are machine pressed while others are simply crafted using small saws to cut the metal with little in the way of filigree techniques. The new items are mostly in light gold or silver gilt with little resemblance to traditional styles and designs (Figure 8).

With the classic silver styles no longer in demand, less and less such objects such are made and, worse, many older pieces are being melted down and recycled.

With the loss of the traditional jewellery and the domination of newer styles which pay little reference to local culture and traditions, Libya is losing an important part of its heritage. Sadly, it is also failing to keep a record of it in museums or published articles. As a result, it seems time is running out for detailed and well-presented record of the Libyan jewellery, its types, use and how it is linked to Libyan society, its heritage and history.

True, there are small collections of traditional Libyan jewellery in some of the museums in Tripoli. Most of the rare and interesting items, however, are held by private collectors who are scattered across many countries in the world. There is, moreover, little coordination or networking which would help to save the knowledge about Libyan and North African ethnic jewellery.

There has been almost nothing written about it, the notable exception being the aforementioned book by Elena Schenone Alberini, published by Araldo de Luca in Italian in 1998 and in English the following year.

The other exception worth mentioning in this vanishing story is the Ethnic Jewellery Forum, founded and directed online by Sarah Corbett (http://www.vividtrading.com/forum) with over 1,200 members from various parts of the world. In this forum, members interested in the jewellery of North Africa and the Sahara exchange ideas and discuss their collections, posting photographs, having other members to comment on them, discuss them, and more besides. The forum also posts some articles about ethnic jewellery well worth reading.

[/restrict]