By George Grant.

Tripoli, 30 June 2012:

If Libyans are feeling a little confused about the imminent National Conference elections, then they aren’t . . .[restrict]alone. Rarely has anyone been confronted with what appears to be so much choice, and yet at the same time so little – and with such paucity of information.

Fully 130 political parties are standing for election on 7 July, putting forward no fewer than 1,207 candidates between them. And that’s just for the first 80 seats up for grabs in the National Conference. Even more of an enigma are the 2,501 candidates running as individuals for the remaining 120 seats. Obviously, these individuals are not standing for election everywhere, but even when you break them down into their 73 constituencies, that still leaves Libyans with an average of 34 candidates each to choose from.

The Political Parties

Amongst the political parties, four main groups have emerged as the punters’ favourites, and the Libya Herald will be providing a profile of each in the coming days.

First is the Justice & Construction Party (Hizb Al-Adala wa Al-Bina), the political arm of the Muslim Brotherhood in Libya, which is fielding 73 candidates. The party is led by Mohammed Sawan, a Misratan and former political prisoner under Qaddafi. Arguably the most organised of the parties, Justice & Construction’s banner of a rearing brown horse set against a sunny blue sky now appears everywhere around the capital Tripoli. Many of their members are highly educated and well connected, and they will be hoping to receive a boost from the victory of the Brotherhood’s candidate Mohammed Morsi in the Egyptian presidential elections on 24 June.

Then comes the Nation Party (Hizb Al-Wattan), which has the backing of the Islamist cleric Ali Salabi and counts the former emir of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) and former head of the Tripoli Military Council, Abdul Hakim Belhaj, amongst its members. The party is fielding 59 candidates, and its purple-tinged banners are perhaps equally as ubiquitous as Justice & Construction’s. The party is believed to be popular with former revolutionary fighters, and has been described as something of a ‘working man’s’ party in terms of its popular appeal.

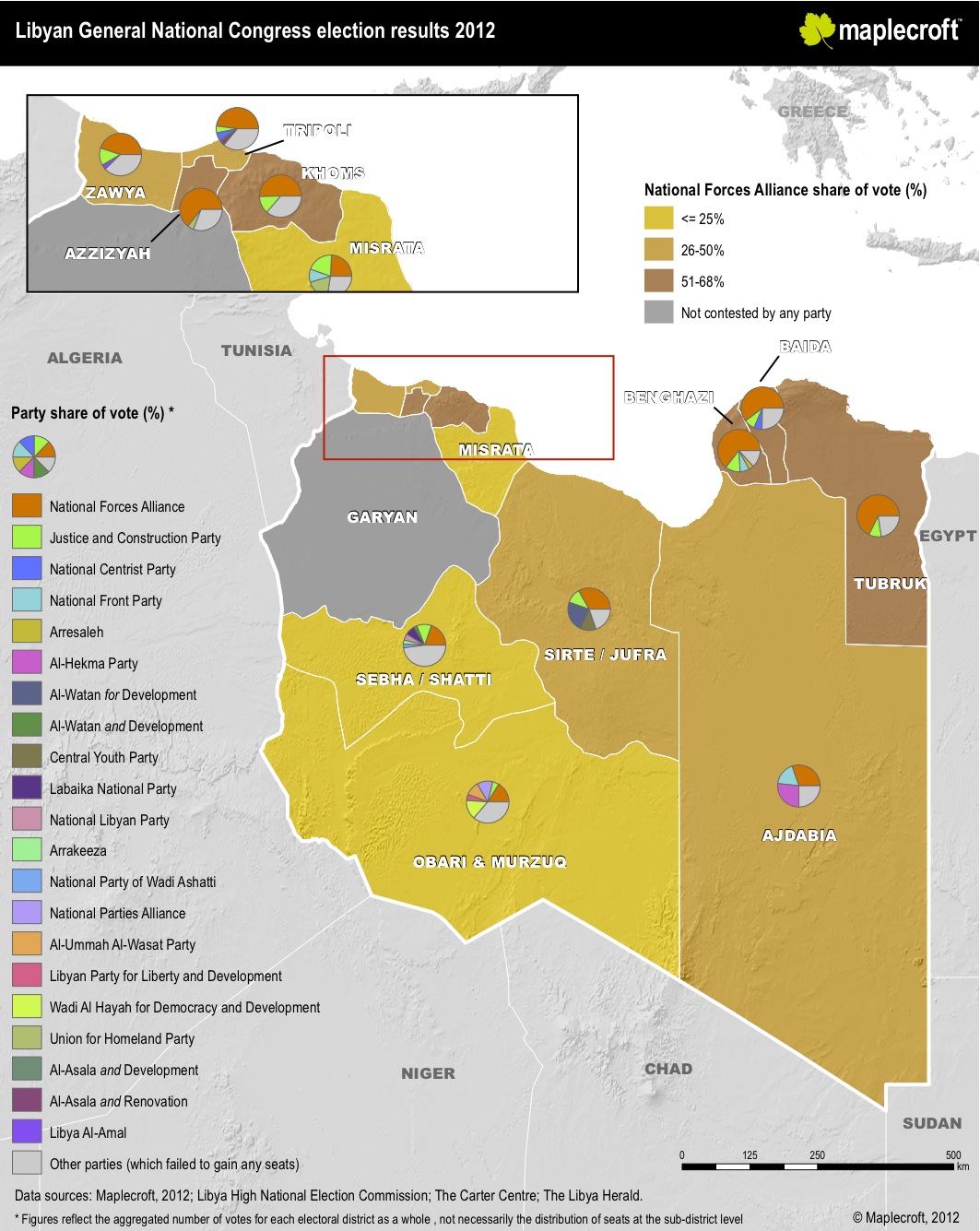

Third is the National Forces Alliance (Tahaluf Al-Quwah Al-Wataniya) a coalition of 58 political parties supervised by Mahmoud Jibril, who served as interim prime minister under the NTC during the revolution and as head of the National Economic Development Board (NEDB) under Qaddafi before that. Although technically not a single party, the National Forces Alliance is standing as a single political entity at the elections. The party has commonly been described as towards the ‘liberal’ end of the political spectrum, and it counts large numbers of Libya’s extensive overseas diaspora amongst its members. The National Forces Alliance is collectively fielding 70 candidates.

Finally, there is the National Front Party (Hizb Al-Jabha Al-Wataniya), led by Mohammed Magaraif, which is putting up 45 candidates for election. Prior to 9 May, the party was known as the National Front for the Salvation of Libya (NFSL), and it distinguishes itself as having led a consistent opposition campaign against Qaddafi since its inception in 1981, albeit mostly from overseas. The party hopes that this continuity of presence and its credibility as a long-established pro-democratic and anti-Qaddafi force in Libya will help it in the elections.

Other big parties, at least in terms of the number of candidates they have standing, include the Union for Homeland (Al-Ittihad min Ajl Al-Wattan), led by the long-time anti-Qaddafi dissident Abdel Rahman Al-Suwayhili (60 candidates); the National Centrist Party (Hizb Al-Ummah Al-Wasat), sometimes described as the “political wing of the LIFG” and counting amongst its number the prominent LIFG member Sami Mustafa Al-Saadi (43 candidates); and the Party of National Development and Welfare (Hizb Al-Watani Liltanmia wa Al-Reaya Al-Egtemaya) with 50 candidates.

Islamism vs Secularism – a false dichotomy

What tends to distinguish these parties is not so much their diversity as how little difference there seems to be between them, at least in terms of their public declarations. Although there may be some merit in attempting to place these parties along a ‘liberal-to-pious’ political spectrum, the division between Secularists and Islamists so beloved by outsiders looking into Libya is a false one. Jibril’s National Forces Alliance is a case in point. At the coalition’s launch, prominence of place was given to a leading Sheikh from Zintan, whilst proceedings were introduced by a woman in high-heels, a ‘hijab-chic’ and a skintight black catsuit.

Ali Salabi has previously denounced Jibril and his followers as “extreme secularists”, although Jibril has repeatedly denied this. Salabi, for his part, has been denounced variously as an Islamist extremist and a Qatari stooge, labels he isn’t happy with either.

In fact, it is very difficult to find a Libyan, either within the parties or on the street, who would describe himself as secularist, with an overwhelming majority insisting that Islam must play an important role in political life, meaning that Sharia forms the basis of the law. At the same time, however, few seem to believe that this aspiration is incompatible with a multi-party democratic society in which women can work and vote, freedom of speech is respected and international human rights covenants are honoured. Certainly, there are radicals on either end of the spectrum, but for the most part it is a matter of degrees.

Views on Women

You won’t find many many Libyans who’ll argue that women shouldn’t have the right to work and vote, and the same is true of the political parties. Indeed, if any of the parties did have serious principled objections to women having a role in political life, they’d have trouble standing in these elections at all, because the law requires them to field as good as 50 per cent female candidates.

Ironically, this makes it rather harder to ascertain where the parties stand on womens’ rights generally; a good indicator would certainly have been the number of female candidates each had standing if the quota had not been in place. One thing is for sure, however, there aren’t many women out campaigning for the Justice & Construction Party in catsuits.

The fact that there are just 84 women standing as individual candidates as against 2,417 men clearly demonstrates that Libya has some way to go before attaining full female equality, but that hardly distinguishes it from a great many other countries internationally. The consensus is that those women who did wish to stand chose overwhelmingly to concentrate their efforts where they have the greatest chance of success: the political parties.

Certainly, attitudes towards women are far removed from those prevailing in places such as Saudi Arabia and some of the Gulf States, in the urban centres at least. It should not be forgotten that it was a woman, Najat Al-Kikhia, who received most votes in May’s Benghazi Local Council elections, winning by more than twice the margin of her nearest male rival.

Party ‘Manifestos’

At this early stage in Libya’s democratic life, it cannot be said that much nuance has been developed between the parties’ positions on issues such as healthcare, defence, foreign policy, education and the economy. All declare their wish to develop a strong and independent Libya, in which citizens have jobs, schools and hospitals are well run and the militia are either disbanded or incorporated into the national army and police. All very well, but – understandably enough perhaps – there doesn’t appear to be much of a strategy for how to reach that point as yet.

Certainly, divisions between what would be called Left wing and Right wing such as exist in more developed democracies have yet to emerge. What perhaps can be said is that this is a nation of aspiring free-marketeers, in which the desire to privatise many nationalised industries enjoys widespread support. The opposite of what existed under Qaddafi in other words.

On matters of foreign policy, circumstance will to a large extent demand pragmatism. Libya is a vast country with porous borders, a weak military and an underdeveloped infrastructure. Regardless of the fact that he is wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) on charges of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity, Sudan’s president Omar Al-Bashir is a regional neighbour, and will be worked with as such. The fact that he – out of long-running anti-Qaddafi sentiment – supported the revolution also helps.

What can be said is that Libya is a country now looking north to Europe and sideways to its Arab neighbours more than south to Africa, Qaddafi’s favoured stomping ground during the final years of his eccentric rule. Although Russia and China will have to be dealt with by virtue of their global size and strength, the latter especially, Libyans of all stripes have repeatedly made clear their desire to work with nations such as France, the United Kingdom and the United States, who played major roles in supporting them during last year’s revolution. Israel, both on account of historical reasons and because it is widely perceived as having opposed the Arab Spring uprisings, remains persona non grata.

In terms of favoured political systems, it is not clear whether Libyans will opt for a parliamentary or a presidential model when it comes to drawing up the permanent constitution after the 7 July elections, although opinion seems to be tilting towards the former, nor is it clear the extent to which power will be concentrated in the centre or in the regions. Much may depend on the balance of influence in the National Conference, which is why such a large number of people in the East are now voicing considerable disquiet ahead of the vote.

Eastern Libya and the ‘Federalist Question’

Currently, the road between Eastern and Western Libya remains blocked by the self-declared Cyrenaica Transitional Council (CTC), which they closed to military and much commercial traffic on 20 June. The CTC say they set up the blockade, which sits on the historic dividing line between Cyrenaica (East) and Tripolitania (West) Libya at Wadi Al-Ahmar, in protest at what they perceive to be the unjust distribution of seats for the National Conference. Currently, there are 60 seats reserved for the East as against 100 for the West, and 40 for the South.

This allocation was drawn up along demographic lines, but large numbers of Eastern Libyans fear this will leave them in a comparatively weak negotiating position when it comes to drawing up the constitution and deciding who gets what. Historically neglected under Qaddafi, Benghazi and other eastern towns do not want to suffer that fate a second time. The NTC argues that it adequately addressed these concerns with the Article 30 Amendment to the 3 August 2011 Constitutional Declaration.

This amendment stipulates that the actual committee tasked with drawing up the constitution will have equal representation from East, West and South, with each providing 20 delegates. The amendment also states that in addition to ratification by a simple majority in a nationwide referendum, ratification will also require a two-thirds plus one majority in the National Conference, meaning the East could still block it if they wished.

Most recently, the interim government has suggested that appointment to the constitution-writing committee could be decided by regional bloc votes within the National Conference to ensure each part of Libya got the representatives on the committee they wanted.

In spite of all this, many Easterners seem unplacated and there have been suggestions of an election boycott and even a Cyrenaica declaration of independence. As a widespread phenomenon, the former outcome remains unlikely and the latter almost certainly won’t happen as things currently stand. The CTC have said that they favour Cyrenaica having its own flag, anthem and clearly delineated borders, but their leader, Brigadier-General Hamid Hassi, has made clear that the group does not advocate independence. It would also be wrong to use the CTC as a synonym for Eastern public opinion, with many and perhaps the majority opposing its federalist aspirations.

One of the problems with ascertaining who stands where on the federalism question is that it seems to mean different things to different people. When understood as effective independence, a clear majority of people oppose it, including in the East. When understood as autonomy with political and legal ramifications, it is still opposed, including by the big parties, but clearly less so in the East. When understood as decentralisation, however, the concept is given a positive reception all over Libya and major parties including the Justice & Construction Party, the Nation Party, the National Front and the National Forces Alliance have all said they support it.

The South

A desire for greater representation and attention, if not autonomy, also exists in Libya’s expansive South. Inevitably neglected by Qaddafi, many southern towns are in fact little more than desert hamlets, with minimal infrastructure and isolated from the rest of the country.

With smuggling representing such an important part of the South’s economy, whatever anybody says, control of these routes has also contributed to the balance of power as well as affiliations and conflict. It would be fair to say that successful elections in the south could alter the balance of power in many parts, meaning that any existing power brokers left on the wrong side of the fence will have a vested interest in seeing them fail. Nevertheless, attracting greater investment into the region will be a priority for almost everybody.

One significant factor to consider is the declared aspirations of the Tebu for the National Conference and the writing of Libya’s permanent constitution. The ethnically-black Tebu not infrequently come into conflict with their Arab neighbours, and much of the recent fighting around Kufra and Sebha has been between Tebu and certain Arab tribes, as well as latterly forces deployed by the transitional government.

At the official launch of the Tebu National Assembly (TNA) on 3 June, Tebu leaders chose not to emphasise their distinctive identity or their aspiration to be respected as a separate but equal group within the country, but rather their desire to work towards closer relations with Arabs and to be an integral part of the Libyan nation. Certainly, words count for less than deeds, but it is notable that either route would have sounded perfectly respectable in post-Qaddafi Libya. They argued that just as they had taken a leading role in opposing Qaddafi during the revolution, so they wished to play a full and active role in the National Conference and in developing the permanent constitution.

The Individual Candidates

Finally, what of the individual candidates themselves, who remain for the most part the great unknown in this election? Certainly, it would be safe to assume that the majority will reflect the concerns of those parts of Libya which they now seek to represent, but building up an overall picture is almost impossible by virtue of the sheer numbers involved and the short period of time they have had to establish their profiles. Many of them will be familiar faces to Libyans in the constituencies in which they are standing, but with official campaigning have only begun on 18 June, all the candidates have had less than three weeks to build a proper platform. As is the case with the political parties, there is also the added problem that all of the individual candidates remain to be tested.

This dearth of information about individual candidates is of course extremely ironic, given that they will actually form a majority within the National Conference, holding 120 seats between them to the political parties’ 80. One of the most important questions is therefore how many of these individuals are actually affiliated, albeit unofficially, with the parties, and where the remainder will go once the Conference is formed. It is widely assumed that most of the individual candidates favour one party or another, just like every other citizen, and some informed Libyan analysts believe the campaign slogans on the posters of individual candidates often belie their party political sympathies. As a prediction, it seems fairly safe to say that the majority of the individual candidates won’t stay independent for long once the National Conference is formed.

Conclusion

A cliché it may be, but the only certainty about this election is that nothing at all is certain. Libya is, to all intents and purposes, taking a plunge into the unknown and only the most self-assured of analysts would make hard and fast predictions about who emerges from the other side, and in what shape. What does seem more certain, however, is the near universal desire on the part of Libyans to see this transition to democracy succeed. This is not a country that looks to the Taliban as a model for government nor is it one that thrives on conflict. It is notable that the Warriors Affairs commission recently found that of the more-than 200,000 militia surveyed, 70 per cent favoured a return to civilian life, with the remaining 30 per cent declaring an aspiration to join either the regular army or police.

A mixture of factional infighting, inexperience and logistical shortcomings would be the most likely reasons for failure, much more so than dangerous and misguided ideologies. It’ll soon be up to the newly elected National Conference members, whoever they are, to work out in practice what those grandiose slogans of theirs actually mean.

George Grant can be found on Twitter at www.twitter.com/GeorgePBGrant [/restrict]