By Michel Cousins.

Tunis, 11 March 2011:

Back in 2011, during the Libyan revolution that saw the Qaddafi regime swept into the history books, posters of the former King Idris became a common sight on street walls in Benghazi and other places in the liberated parts of the country. They were also held high by young revolutionaries who were not even born when the king died in exile in Egypt in 1983. These images symbolised a lost past, obliterated by 42 years of eccentric yet ruthless dictatorship. Many Libyans still look back at the period between independence at the end of 1951 and Qaddafi’s coup in 1969 – the period of the monarchy – as the country’s golden age, a period of transformation from being the world’s poorest nation to a major oil exporter, a country that was rapidly modernising itself politically, economically and infrastructurally. In the mid-to-late 1960s, some 60 percent of the Libya’s income went on new infrastructure and housing, a figure that has never been seen since. It was also a period of busy social change, with a new middle class developing rapidly and when many new projects started that then came to fruition under Qaddafi.

The 2011 Idris posters notwithstanding, the era of the Libyan monarchy is largely unknown, not only to the outside world but to most Libyans as well. That is because Libya is a young country. Most Libyans are too young to remember it. It is also because Qaddafi, who hated the period like poison, made sure that there would be nothing worthwhile to remember. He made certain that the 1951-69 era was written out of the history books, almost as if it had never existed.

One person who knew it well is Adel Dajani. Born in Libya in 1955, his Palestinian parents had come to Libya in 1950, His father, Awni had become the king’s lawyer and helped in writing the 1951 federal constitution which, 70 years on, is again being championed by federalists and others as the answer to the country’s constitutional vacuum. His mother, Salma, became the close confidant and friend of the king’s wife, Queen Fatima. He himself was brought up as almost an extended member of the Libyan royal family, the childhood palace playmate of the queen’s Algerian adopted daughter Suleima and participant in many a royal holiday and visit, both official and private.

His book, From Jerusalem to a Kingdom by the Sea, just published in London, provides a remarkable insight into the very down-to-earth workings of the monarchy and of royal life in Libya in the 1950s and ’60s. It is very much a first – not because King Idris kept himself hidden from the public gaze, but because no one has previously written with any knowledge or experience about Libya’s monarchy.

What comes out is a story of someone who was not a king in the traditional sense of the word, actively running the country, like kings elsewhere in the region, but more a father figure who saw his role as the focus of Libya’s unity, while making sure that a prime minister and ministers were in office and that the country was properly governed. Once that was achieved, Idris comes over as a self-effacing and devout man who loved not only his country and people but also simplicity, music, books – most importantly the Quran – and very much his wife, the queen.

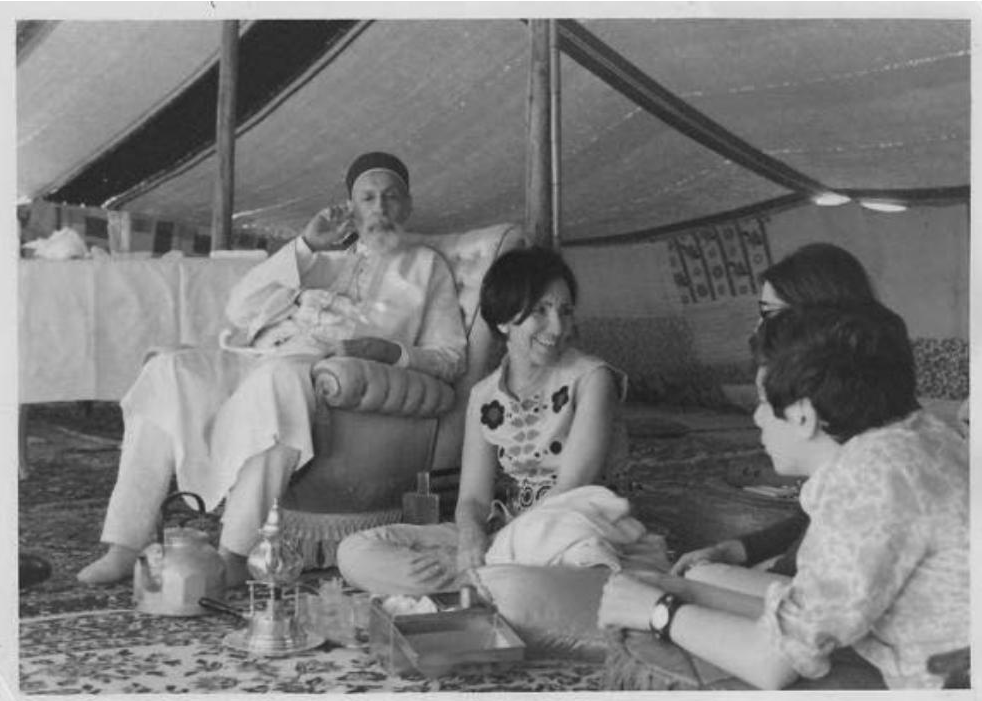

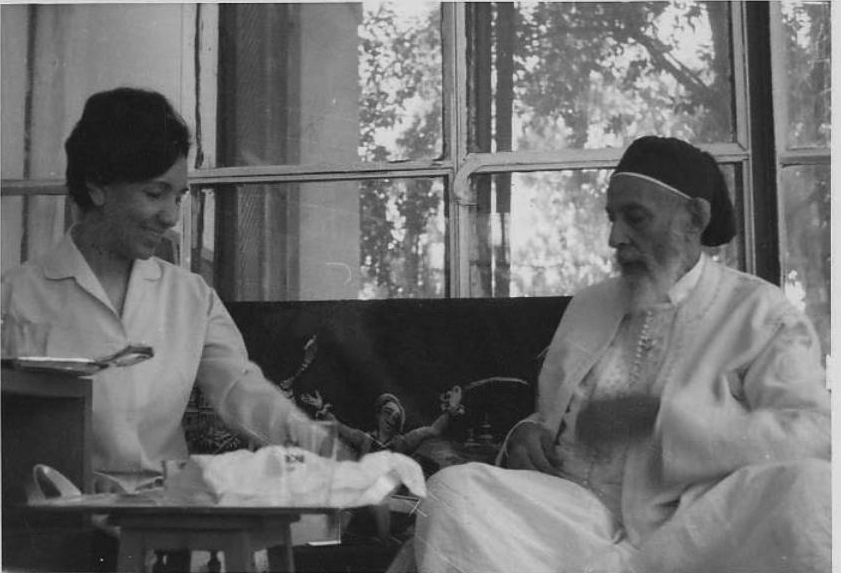

There are enchanting anecdotes of life spent with King Idris and Queen Fatima, who from earliest childhood Dajani called Mawlati, and Suleima – stories of the queen nursing a sunburnt 10-year-old Dajani who had stayed out in the sun too long, of her daily tea-making for the king, of spending the summer with them in Tobruk, the king dressed in traditional Libyan costume, the queen in slacks, and her secretary water skiing in a bikini. Or trips to the desert in convoys of Mercedes cars accompanied by galloping dust-raising horsemen in white burnouses, sharing food around a camp-fire at night, sleeping in simple tents. Then there was the joining in on royal trips abroad, such as to Greece where he and Suleima met King Paul, or to Alexandria to meet Nasser. While there, young Dajani and Suleima were allowed to join the king and queen for lunch with Nasser – just the five of them – only to be overcome by fits of giggles and ordered out of the room by an embarrassed queen and given a royal telling-off by her, although apparently Nasser and Idris found it amusing.

There is much more about life in the “Kingdom by the Sea”, the Libya of the monarchy. There is life at his first school, Tripoli college, the British-run top school in the country; the regular beach parties that were an integral part of life for many Libyan and foreign youngsters in 50s and 60s Tripoli; American TV beamed from what was Wheelus airbase, now Mitiga Airport, one of the largest American airbases outside the US. Life in a gentler and happier Libya. Then being packed off to England, to prepare for the entrance exams to Eton, the elite boarding school west of London that has educated the second in line to the British throne, Prince William, his brother Prince Harry, the British prime minister Boris Johnson and his predecessor but one, David Cameron, among many prominent UK personalities. Dajani was not only the first Libyan at Eton, but apparently also the first Arab.

But the book is about much more than a young life in the cosmopolitan and outgoing Libya of the 1950s and ’60s. This is a poignant story of loss and recovery, not just once but twice, set against the background of political cataclysms of the Middle East and North Africa region from 1948 through to the Arab Spring of 2011 – a story of a Palestinian family losing home and country in 1948, finding a new home, a welcome and a new identity in Libya, suffering again in 1969 with Qaddafi’s coup but managing to hang on there for another nine years before losing home yet again and forced into exile. In between, there are stops and refuges in Cairo and London and later in Tunis and Hong Kong and, in Dajani’s case, finally returning home to Tripoli. It is compelling. It also lays to rest some of the enduring disinformation about Libya’s history, such as that Qaddafi overthrew King Idris in September 1969 and that the monarchy and its governments were corrupt.

As Dajani points out, the king had grown weary with the burdens of politics, had decided to abdicate and had in fact left the country. It was from Athens in August 1969 that Idris announced his abdication, which was to come into effect on 2 September. Qaddafi managed to fill the political vacuum by staging his coup the day before. Moreover, as Dajani also notes, Idris afterwards insisted that he could not in all conscience accept any funds as head of state because he no longer was king.

The first part of the book, an account of Dajani family life in Palestine is no less fascinating. They had been a prominent Palestinian family in Jerusalem for almost one and a half thousand years. The first member there was Al-Mansi who accompanied the Caliph Omar when he received the surrender of Jerusalem in 637, and stayed on. Nine hundred years later, the Ottoman sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, gave to another Dajani, Sheikh Ahmad Al-Sharif, and to his descendants the custodianship of the Tomb of David, revered and honoured by Muslims, Jews and Christians alike. In the room above the tomb is the Cenacle, a reputed site of immense importance to Christians – the Upper Room where Jesus presided over the Last Supper. The tomb remained in the Dajani’s custodianship until 1948.

The book is beautifully an sensitively written. The smell of orange blossom, of Palestinian and Libyan cooking almost waft off the pages.

For most readers, the more recent events of the Arab Spring in Tunisia and Libya are familiar enough, but seeing them from the personal angle of the author and how they affected him and his family is no less fascinating, such as organising neighbours in his Tunis suburb during the Tunisia Revolution into a sort of local defence unit to guard against looters.

This is a bitter-sweet account of five decades not just of loss and recovery but of resilience and it is peppered with reminiscences and anecdotes of worlds now vanished. It was a delight to read. For those interested in Palestinian and Libyan history it is a must.