By Sami Zaptia.

London, 27 June 2017:

Libya remains the main source of destabilization of the Sahel countries and the state seems to have a minor presence in the vast southern porous region, a report released this month states. The report says that a military solution would not solve the region’s problems. The Libyan conflicting parties need to find accord and a strong Libyan state needs to be re-established with effectiveness on its southern borders. But the border states must also satisfy the needs of their minorities living in this border region in order to create long term stability, the report concluded.

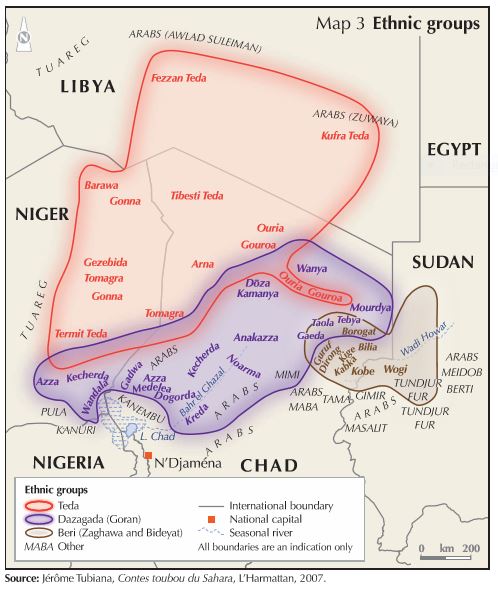

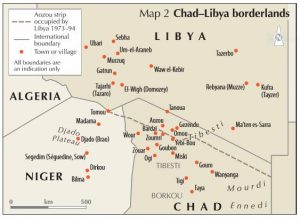

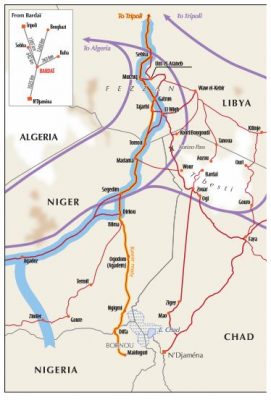

The 192-page report, Tubu Trouble: State and Statelessness in the Chad– Sudan–Libya Triangle by Jérôme Tubiana and Claudio Gramizzi says that Libya’s instability, and the continuing violence in Darfur are chief among the many factors causing the internationalization and growing autonomy of armed factions in the region.

It states that between 2011 and 2013 illicit weapons flows from looted Libyan arsenals transited through northern Chad. These flows seem to have dried up, but flows of individual weapons persist and supply the local market in northern Chad. Demand remains relatively high and has increased in reaction to the Tibesti gold rush. Easy access to Libyan weapons has further contributed to the militarization of Chadian Teda (Tebu) society.

Between 2011 and 2013 a spectacular series of gold discoveries took place in the Sahel and Sahara in an arc stretching from Sudan to southern Algeria. The gold rushes that occurred in North Darfur and then in Teda territory in Chad, Libya, and Niger had an important impact on both local populations and armed actors in northern Chad, southern Libya, and western Sudan.

New towns of several thousand inhabitants appeared in the middle of the desert on both sides of the border. Tankers delivered water supplies from Libya, while food, generators, metal detectors, mercury, and other mining equipment came mainly from Libya and Sudan. On the Libyan side of the border the majority of the gold miners seem to have come from Chad, although they were not necessarily Teda.

Access to gold mines in Libya was controlled by Libyan Teda militias, who occasionally levied taxes on both gold miners and traders.

On the role of the state, the report says that the state seems remote everywhere in the region. The presence of institutional armed actors—ideally armies that are truly national—is certainly necessary, whether to support the return of the state or to enforce the rule of law, for example in matters related to gold mining.

But in contexts in which the respective government forces have for so long been seen as enemies by local populations, to concentrate efforts on an essentially military response or presence would undoubtedly be an error of judgement.

This is because the hostility of the environment and the area’s sheer size would require the use of disproportionate operational and logistical resources that would inevitably achieve incomplete results.

Similarly, the Libyan crisis and the issue of a jihadist presence in the Sahara will not be resolved by a military intervention in southern Libya or by placing Western soldiers along porous and virtually non-existent borders.

The solution, which depends largely on the Libyans themselves, is to re-establish a government in Tripoli that controls the whole of Libya distant that, for now, northern Libya’s divisions will likely encourage the centrifugal tendencies of the country’s southern actors.

The importance of the presence of the three states (that is, Libya, Chad, and Niger), not only militarily, but also in terms of providing services and development, cannot be underestimated. The region and its populations will only be able to fulfil the role of a barrier against the chaos in Libya if their needs are taken into account.

Any attempt to stabilize the region should therefore include the provision of basic services. This would allow the Teda and the other communities that surround them to feel that they are full citizens of whichever country they happen to live in.

The report said that only local projects that are wanted by local communities will enable their members to live on their lands, farm their oases, educate their children, have jobs in their villages, and ultimately build assets to be defended instead of giving in to the temptations of exile and the easy gains derived from trafficking and war.

Stabilization will take time and political will; for now, Libya is likely to remain the main centre of attraction for Teda populations looking for a means of subsistence. But no matter how precarious life there may be, Tibesti will always remain the ‘house’ and ‘home’ of the Teda from the three countries, to quote a Teda intellectual from Niger.

The report concludes that it is essential that more attention is paid to the vast Tebu territory and the Chadian–Libyan border areas. This problematic area is geographically marginal, yet central to regional security.

It adds that it is crucial not to limit the focus solely to the military dimension, however, as the Western interventions in response to the crises in Libya and northern Mali have done. Instead, socio-economic interventions should be adapted to the needs of local communities and aim to integrate them into the state.

Without this, the report says, there is a clear danger of these communities on the borders of northern Chad, southern Libya, and northern Darfur becoming even more marginalized in their respective countries. This could in turn result in even more young men offering their services for hire (as militiamen, rebels, mercenaries, or bandits) or engaging in cross-border trafficking.

Tubu Trouble: State and Statelessness in the Chad– Sudan–Libya Triangle by Jérôme Tubiana and Claudio Gramizzi is a co-publication of the Small Arms Survey’s Human Security Baseline Assessment for Sudan and South Sudan and the Security Assessment in North Africa with Conflict Armament Research.