By Sami Zaptia.

London, 27 July 2016:

The international community led by UNSMIL see that increasing Libya’s oil production is key to empowering the Faiez Serraj-led Presidency Council/Government of National Accord (PC/GNA), the only internationally recognized government in Libya.

They see that increased Libyan state revenues could give room for Faiez Serraj to solve some of the country’s mounting and acute problems such as a confidence deficit, extremism, illegal migration, insecurity and high crime rates, the budget deficit, inflation and high prices, cash shortages at banks, medicine shortages, power, water and internet cuts and the internally displaced Libyans escaping regional clashes.

As a result, UNSMIL head, Martin Kobler met in the eastern oil port of Ras Lanuf last week with regional strongman and Petroleum Facilities Guard leader Ibrahim Jadhran in an attempt to restart production in Libya’s stalled eastern oilfields.

Jadhran has been preventing the export of oil from the local coastal oil port terminals under his control since the time of Prime Minister Ali Zeidan back in August 2013. As a result, Libyan oil production has plummeted from a post Qaddafi high of 1.5 million in 2013, down to anything from 200,000 to 400,000 bpd.

However, after the Kobler-Jadhran meeting, a group of tribal leaders claiming to represent the inland regions where the eastern oilfields are located, as opposed to where the oil exporting ports are located, have thrown a spanner in Kobler’s plans by distancing themselves from the Kobler-Jadhran meeting and of any agreement that might emerge from it.

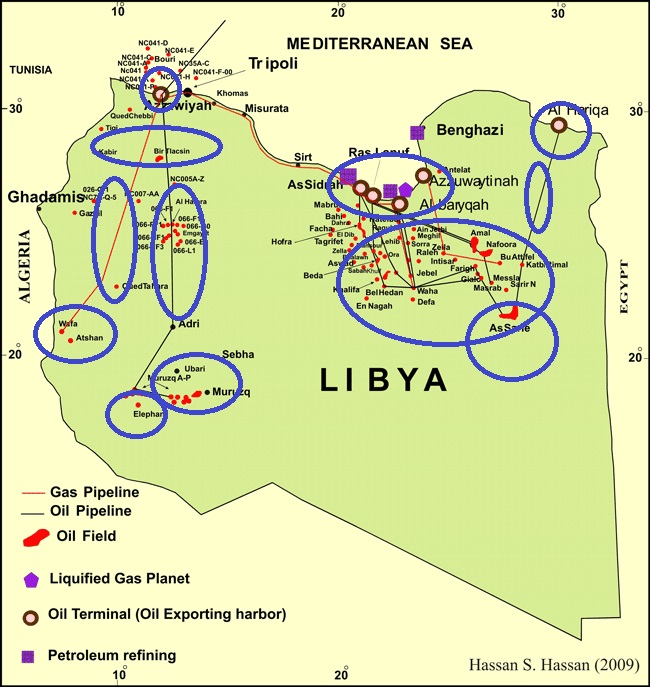

They point out that while Jadhran may have control over the oil exporting ports and storage tankers at the end of the pipelines, Jadhran does not have control over the actual inland production oilfields nor the pipelines that lead up to the coastal oil terminals and ports.

The tribal leaders insist that Kobler must talk to them separately and strike a separate deal with them if he wishes to restart Libya’s oil production. Moreover, they declare their political allegiance to Hafter, the internationally unrecognized Thinni government and the House of Representatives in Tobruk.

To make things worse, in a leaked letter sent to Kobler after his meeting with Jadhran, Tripoli National Oil Corporation (NOC) chairman Mustafa Sanalla tells the UNSMIL chief that his NOC will not lift the state of force majeure it has declared on the oil ports and terminals blockaded by Jadhran in fear of possible costly legal claims against the NOC by damaged foreign EPSA partners and other parties.

Initially, UNSMIL may have thought that if it succeeded in simply reuniting the two western and eastern administrations of the NOC in Tripoli and Benghazi, it could succeed in restarting Libya’s oil production. However, it is clear now that the problem of increasing Libya’s oil production was never an administrative problem. The problem of increased oil production now rests out in the oilfields, pipelines, terminals and ports – and in the populations surrounding and controlling them.

Speaking on Libyan TV, Naji Magharbi, the chairman of the Benghazi-based NOC, also condemned the Kobler meeting with Jadhran stressing that Jadhran had no legal authority to lift the force majeure on the ports and resume oil exports. He added that the conflict over oil exports would not end with the decision to open or close the oil ports, but with bringing security to the community.

Kobler must now mediate between the three parties: the two NOC’s and Jadhran in a complex and delicate three-way tug-of-war, balancing his keenness to quickly resume oil production with issues of setting a precedent, legitimacy and political sensitivities.

The same principle applies to Libya’s western oilfields. NOC sources have told Libya Herald that discussions have been ongoing at a technical level to increase oil production from Libya’s south/western oilfields.

The hope was that the oilfields in the Hamada al Hamra and Murzuk basin could quickly ramp up production in the short term to around 600,000 bpd. Optimists think that between the east and west production could be increased to 800,000 in the short term and up to 1.2 million bpd within six months.

This would be a great boost in the arm for Libya’s deficit-ridden government. US Special Envoy for Libya, Jonathan Winer has said that the economic reality is that Libya cannot pay its salaries, invest in needed infrastructure or maintain its economy unless it pumps a minimum of 800,000 bpd.

However, the problem with increasing production from the south/western fields is not at the Zawia terminus port on the coast or at the oilfields themselves. Production has been deliberately reduced in a political move by Zintan. They have partially closed the valve/valves of the pipeline in the Riyayna region, about 40 km away from Zintan, travelling from the southern oilfields to Zawia oil port and refinery. Indeed, all four pipelines from Sharara, Al-Fil (Feel), Al-Hamada Al Hamra and Wafa fields pass through a valve station in Riyayna.

The on-off closure of the Sharara oilfield in the Murzuk basin is a perfect example. It is operated by Akakus Oil, a NOC-Repsol joint venture. It was taken over by pro-Libya Dawn Tuaregs and members of Misrata’s Third Force in November 2014 loyal to the de facto Tripoli administration at the time. They had forced out the Zintani and Tebu forces who had been guarding it.

The Eni Fil/Feel (Elephant) field, however, is controlled by Tebus. The two fields are only a few km apart, but indicate the intricacies of post-Qaddafi Libya’s politics. All the fields in the Murzuk basin use pipelines that run past Zintan to Zawia port.

It is not clear what the political deal and quid pro quo that the Serraj-led PC/GNA is going to be offering the Zintanis. It is not clear even if the PC/GNA had initiated or supported Kobler’s meeting with Jadhran. Whats is clear is that the Tripoli NOC was either not consulted or over-ruled.

It will be borne in mind that one of the nine members of the Presidency Council representing Zintan, Omar Aswad is currently boycotting the Presidency Council. Presidency Council member Ali Gatrani who represents the east is also boycotting the body.

How likely is it that the seven other non-boycotting Presidency Council members will be able to convince Aswad to end his boycott and convince his city to open up the Riyayna pipeline valve? How likely is it that Kobler will be able to bypass Aswad and appeal directly to the city of Zintan itself? Zintan, it will be recalled, had turned back Kobler’s security advisor Paolo Serra when his plane landed at Zintan airport back in May this year.

If Jadhran is indeed rewarded for his oil ports blockade, it will enshrine the principle and precedent for all other power centres. Libya’s oil production facilities could prove to be the ideal tool for the various contending Libyan power centres to express their political differences and fissures.

Oil facilities blockades could become the perfect mechanism to get heard and noticed in the distant urban political centres of Tripoli, Benghazi, Beida, Tobruk, Misrata or Zintan. This is exactly what Mustafa Sanalla said to Kobler in his (leaked) letter

Zintan is firmly allied with Hafter, the Thinni government and the House of Representatives in the east. What would be the incentive for Zintan to empower Serraj and his PC/GNA in Tripoli having been forcibly ejected out of the capital by the GNC/Libya Dawn coup in the summer of 2014?

Zintan and its boycotting Presidency Council member Aswad, consider the Serraj Presidency Council to be dominated by Misrata and its ‘’Islamist’’ allies. They see the Presidency Council as being propped-up by the very militias that ejected the Zintani forces out of Tripoli in 2014.

They also object to the failure of the Presidency Council to rule by consensus and to its failure to form a unified non-tribal/city/regional based army which would include its forces as well as the HoR recognized and Hafter-led Libyan National Army

Then there are all the political grievances of the minority Amazigh, Tebu and Tuareg people of Libya – all within striking distance from one sort of oil facility or another that are scattered across the 1.76 million square km of Libya: the 17th largest country in the world.

There are two ways of looking at the politics of increasing Libyan oil production. The pessimistic and glass half empty view is that it would be impossible to strike a deal as oil facilities are widely dispersed traversing many local power centres and internecine conflicts.

This makes the numerous oil production, storage and export facilities very vulnerable to the smallest of militias which is able to exert a huge amount of leverage totally disproportionate to its size. Add to this is the myriad of unmet demands by various regional groups such as the Amazigh, Tebu and Tuareg from the centre – it is easy to favour the pessimistic outlook.

Some may even contend that with the widespread dispersion of weapons and militias in post-Qaddafi Libya, the country may have become ungovernable in the classical sense by any one central authority. The inhabitants of the country seem more defined and united by family, tribal, city and regional priorities than national priorities. British ambassador Peter Millett raised this very point in his House of Lords report in July and speculated that it may take some time to create a unified Libyan identity.

However, if Libyans do not unite and cooperate and live in a peaceful civil society they would indeed be destined to a collapse of the easy and relatively prosperous life they had become accustomed to for decades. It is precisely because Libya’s oil facilities are dispersed amongst the different Libyan tribes, power centres, regional and ethnic groups that Libyans need to unite to ensure the continued production and export of oil.

Rentier state Libya presently has no other source of income on tap. If total oil production is ceased, its cash reserves are estimated to be adequate for only two to three years. Libyans must therefore cooperate at least out of pragmatic self-interest in order to ensure the continuation of oil production and exports. That much they may agree upon in principle. The divisions start when it comes to the control and distribution of those oil revenues.

The divisions are many. There is the west-east division, the coastal-interior division as well as the ethnic Arab-non Arab divisions. Currently, due to old historical contracts, Libya’s oil revenues are deposited by foreign importers into bank accounts controlled by the Tripoli-based Central Bank of Libya. Whoever has controlled Tripoli has been able to control the country’s purse strings.

The Beida-based Abdullah Thinni government and the Tobruk-based House of Representatives have found this out to their cost since they were ejected from Tripoli in 2014. Despite enjoying universal international recognition up until early 2016, they were totally incapacitated and unable to project or leverage their legitimacy from the east without control over the oil revenues. This led them to make their unsuccessful attempts to export oil outside the channels of the Tripoli NOC. With the international community resisting this move, the eastern-based authorities were doomed.

In short, while eastern Libya controlled two-thirds of Libya’s oil production, it did not have access to the oil revenues. But equally, whilst Tripoli holds the purse strings it only nominally at least has one third of the country’s oilfields within its region. Both sides need each other to complete the circle.

There is a final kamikaze scenario where the Tripoli authorities refuse to pay the salaries of the other regions or where the remaining few oilfields pumping oil shut down. Libya will be forced to exhaust its foreign currency reserves down to zero.

Post Qaddafi, with the continued contested legitimacy of Libya’s institutions and in the absence of a strong Libyan central state with a monopoly on the legitimate use of force, legitimacy and power have become dispersed to the nth degree. Power and legitimacy have become localized to the extent that Libya has become dysfunctional with no unified aims or processes.

The challenge, therefore, for UNSMIL chief Marti Kobler is how to get all the myriad Libyan power centres around the same table and how to get them to appreciate their interdependence. Then he has to come up with an almost impossible formula for dividing the oil money that is acceptable to all. In effect, Kobler must engage in nation-building, national reconciliation and a process of establishing a Libyan social contract – all in one and at the same time.

This is a process that should have started in 2011 and is likely to take a number of years – which does nothing to solve the long list of acute everyday problems Libyans are facing today. It will also do nothing to save the PC/GNA which the international community is pinning all of its hopes on in order to solve both Libya’s internal problems, as well as fighting IS and stemming illegal migration.

Restarting Libya’s oil production is about much more than opening oil ports or oilfields here or there. Solving Libya’s increased oil production is about solving the post-Qaddafi conundrum of Libya.