By Sami Zaptia.

Tunis, 30 November 2015:

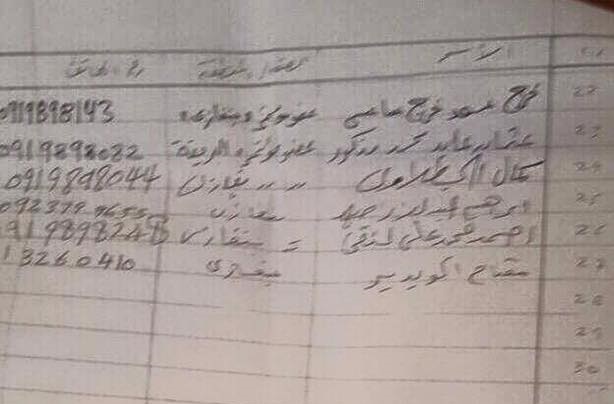

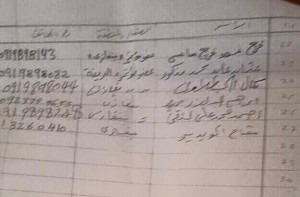

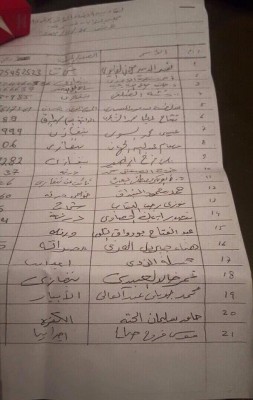

A ground breaking meeting was held last Thursday in Tunis between 27 members from the House of . . .[restrict]Representatives (HoR) and the General National Congress (GNC) in opposition to the UN-brokered Libya Dialogue and proposed Government of National Accord (GNA).

The meeting breaks new ground in Libyan post-Qaddafi politics in that it is probably the first major and publicly announced meeting of members from the two opposing parliamentary bodies. The 27 members are almost all from eastern Libya and refer to themselves as representing the eastern region of Barqa (Cyrenaica). However, not all HoR or GNC members are represented by these 27.

It will be recalled that in July 2014 the newly democratically elected Libyan parliament, the HoR, had to escape the capital Tripoli in fear for their safety and security after a rump of GNC members supported a group of militias (Libya Dawn) in invading the capital.

The HoR was forced to hastily relocate and set up shop in the eastern city of Tobruk. Meanwhile, the rump of anti HoR members from the GNC reconstituted themselves in Tripoli and set up an alternative ‘‘Government of Salvation’’.

Since July 2014 Libyan politics have been defined to a greater extent by these two main political blocks with both parliaments enjoying the support of their group of militias. Moreover, the politics between the two camps had been partisan with both camps refusing to meet face to face over the last year during long-winded UN-led negotiations.

The 27 HoR and GNC members that have met in Tunis do not represent the majority views in both their respective parliaments. Indeed, a majority in both the Tripoli and Tobruk parliaments have publicly announced their support for the UN-led Libya Dialogue and proposed GNA.

However, a minority of hardliners in both parliaments that include the leadership of both houses are reported to be preventing the majority in their respective houses from voting in support of the UN-led GNA.

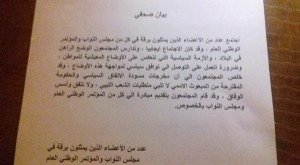

In the statement released in Tunis by the group of 27 the ‘’27’’said that the UN-brokered deal and the GNA “do not meet the requirements, nor are consistent, with the foundations of reconciliation”. They also stated that they had put forward an alternative proposal to both the HoR and the GNC.

No copy of this alleged new proposal has surfaced publicly. Social media has reported that the group of 27 are attempting to find a Libyan solution without what they see as the ‘’guardianship’’ foreign interference. The group are also reported to be attempting to organize a meeting between the two presidents of the HoR and the GNC.

One dissenting HoR member, Younis Fannush, however, distanced himself from thegroup and declared that at this point both the HoR and GNC have failed the Libyan people and that they should

There is no doubt that the Bernardino Leon era as the UN broker in the Libyan talks has led to many Libyans to ask why the two conflicting Libyan camps cannot meet face to face and without any what many suspect is a malignant foreign presence. The revelations about Leon’s alleged possible duplicity as a mediator have highlighted to many Libyans the possible disadvantages of foreign mediation.

The simple answer to the question of foreign mediators is that Libyans are at war with one another and have failed since July 2014 to reach a political settlement with or without third-party external mediation.

However, this latest unexpected twist and marriage of convenience between former arch enemies in post 2011 Libyan politics adds yet another layer of confusion and dynamics at play. It may also help reveal the real as opposed to fig leaf reasons for the Libyan conflict.

The Libyan political and military split between the outgoing GNC and the incoming HoR was initially dressed up as a technicality where the HoR refused to convene in Tripoli to be handed over power by the GNC. It was also portrayed as a fight between the election-losing Islamist coalition against the more secular / liberal winners of the 2014 HoR parliamentary elections.

On another level it was also portrayed as a battle for power between the Misrata-led militias (but include Gharian, Tripoli, and Zawia militias) against the Zintani-led militias. This was portrayed as a battle between the revolutionaries (Misrata) representing the new order against the conservatives of Mahmoud Jibril’s National Forces Alliance (NFA), Zintan and remnants of the outgoing Qaddafi regime.

To add another level and layer of confusion, retired General Khalifa Hafter who is battling ‘‘Islamic extremists’’ in Benghazi and who he claims are supported by the GNC and Misrata, is the head of the HoR’s Libyan National Army.

Hafter, however, whilst supporting and being supported by the HoR, has aligned himself specifically with the pro-devolutionary Barqa HoR members. These are the HoR members who have aligned with some GNC members to form the group of ‘’27’’.

Another leveraging power centre in the Libyan political arena is is Ibrahim Jadran and his Petroleum Facilities Guards (PFG) who are ostensibly government controlled regular soldiers protecting Libya’s main oilfields for and on behalf of the whole of Libya and Libyans.

The reality is that Jadran with his regionally-based PFG militias, whilst like all militias all over Libya, are paid by the central state, but serve their own personal extortionist interests of those of Mr Jadran.

Jadran is currently patiently awaiting a resolution of the political and power struggle between Tripoli and Benghazi-Tobruk-Beida so that he can find a foe to bargain with and extort.

Unfortunately, many Benghazi-based Cyrenaica separatists have not woken up to the fact that if and when Cyrenaica breaks away from the rest of Libya, Jadran will neither be joining them nor handingover control of the oilfields to them. He is more likely to set up his own mini-oil emirate himself based on his Magharba tribe.

Finally, in the realpolitik dynamics of power politics at play in Libya there is the issue of the rentier state and the division of the money from the oil cake. Most realists analysing the Libyan scenario insist that the battle in Libya is an old fashioned classical Machiavellian battle for control of Libya’s oil money which make up 97 percent of its GDP.

In a rentier state were about 2,000 state-employees have the ultimate influence and key to how Libya’s oil money is distributed: Libyan politics is no more than a battle for the control of these key 2,000 state-sector positions starting from the head of the state, parliament, prime minister, government and the other key heads and positions such as the NOC and the LIA.

Al the political output by so-called Islamists, secularists, liberals, regionalists etc is deemed as no more than fig-leafs and window-dressing for money and power grabs.

Whilst these are the main political dynamics at play in Libya, they are by no means the only ones. There is a myriad of tribal, regional, militia, and ethnic dynamics such as the Tebu, Tuareg and Amazigh minorities all seeking their leverage. In the absence of a central regular army loyal to the legitimate state, every militia in Libya is an autonomous power centre.

What is clear is that despite succeeding in holding two elections, Libya is still suffering from its post-42 year authoritarian state legitimacy vacuum. The legitimacy enforced by suppression and the citizenship purchased by the Qaddafi rentier state dissipated with the collapse of the Libyan state during the 2011 revolution.

Hence in the absence of a new social contract backed by a monopoly on the legitimate use of force, everybody has legitimacy and yet no one seems to have legitimacy in today’s Libya. Equally, in the absence of ideological or policy restraint of party politics, Libyan politics are fluid with new alliances being formed between former arch enemies.

In the four years since the 2011 revolution ousted Qaddafi, normal politics or Realpolitik it seems has set in and GNC and HoR members feel able to horse trade to the extent that HoR friends of Hafter feel they are able to openly unite with the GNC members.

In conclusion, the latest political marriage of convenience between hitherto HoR and GNC arch enemies reveals that the political battle in Libya may have been motivated all along by the desire for personal power, money and influence.

The banners of Islamist, secular, liberal, revolutionary, conservative, regionalist and separatist, nationalist may have been no more than transparent fig leafs to justify power grabs.

They were no more, it seems, than the usual political tools used by ambitious politicians to mobilize the public in their support and in opposition to others.

There were never, it seems, any legitimacy, ideological, ethical or policy differences between the HoR and the GNC. It seems that it was all a battle for power, influence and money all along.

One positive than can therefore be gleaned from this is that if current Libyan politics is indeed not based on uncompromising ideology or principles but on power, influence and money, then it follows that horse trading can occur, compromise can be reached and bargains can be struck to reach a political consensus. It is just a matter of finding the right acceptable formula of slicing up the Libyan oil-money cake that pleases all parties. [/restrict]