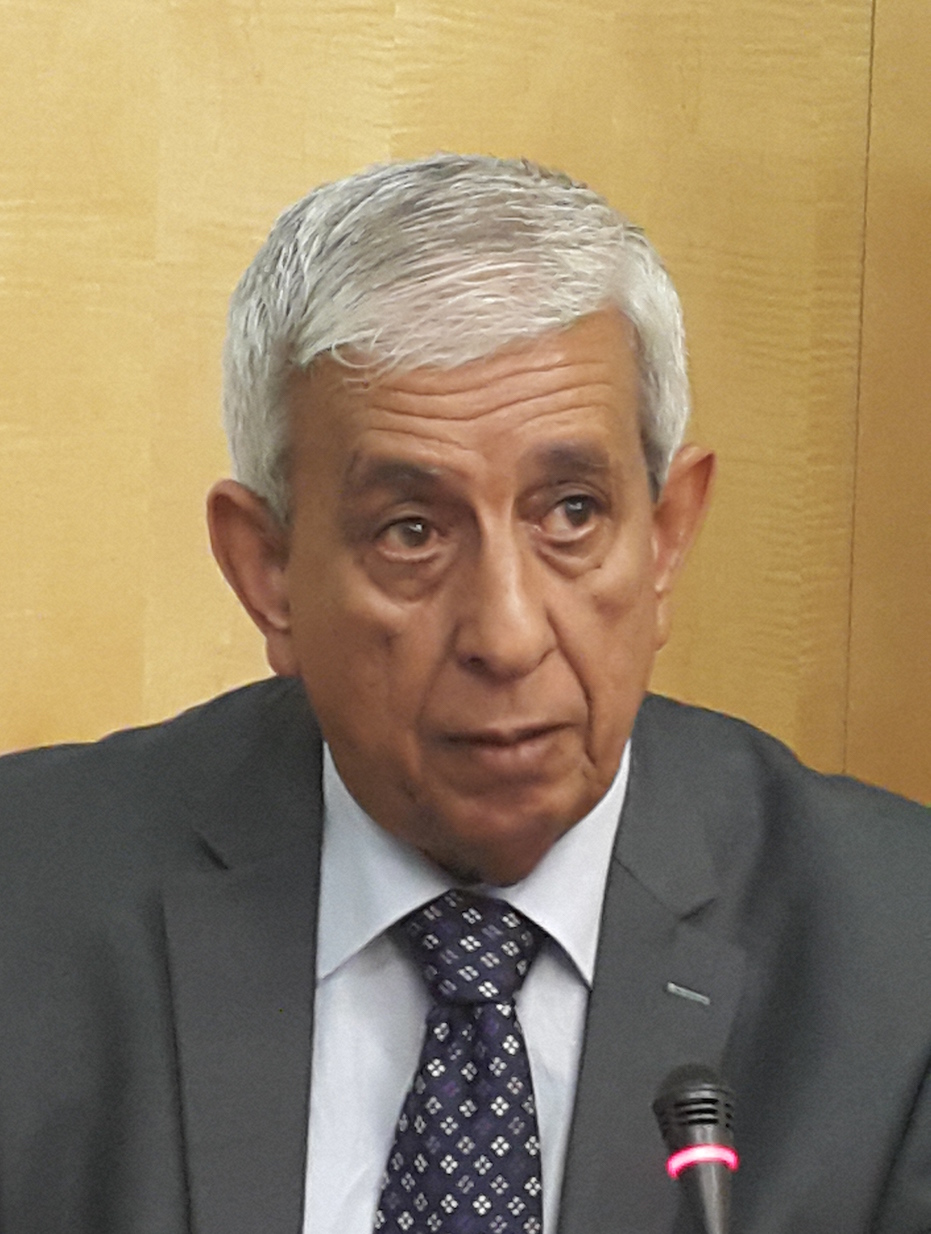

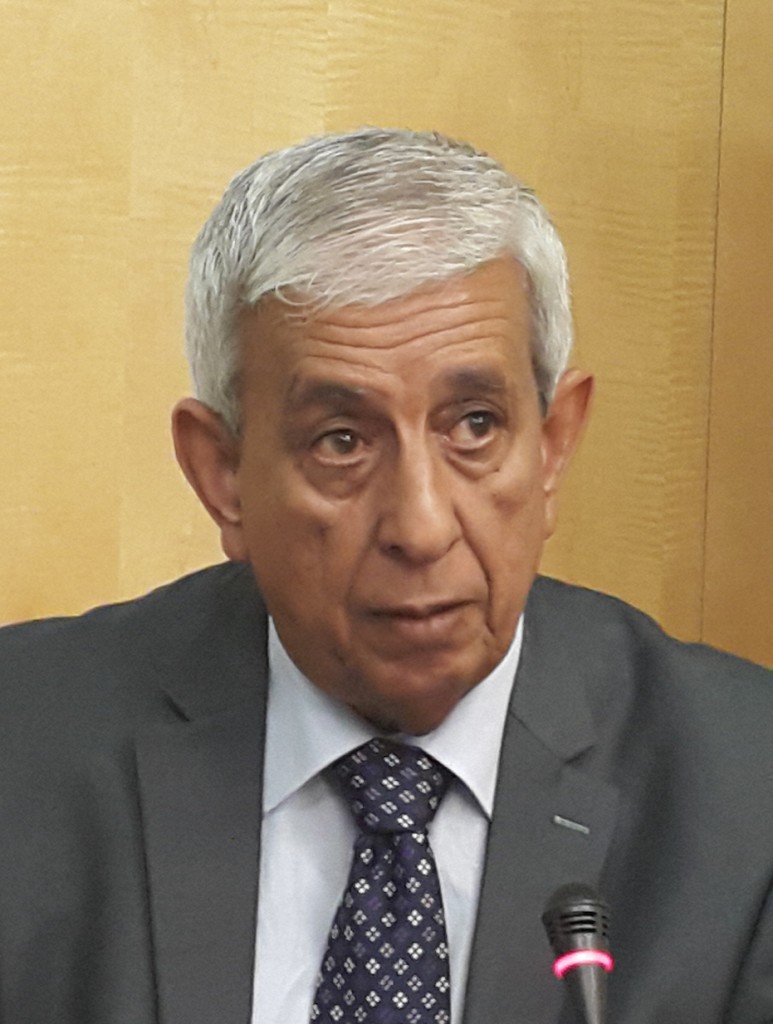

Mustafa El-Huni is one of the . . .[restrict]12 people nominated by the House of Representatives for the posts of Prime Minister and one of the two Deputy Prime Ministers to be chosen by the Libya Dialogue participants next week.

An economist, educated in both Libya and the US, he joined the revolution at the start in February 2011 becoming first deputy president of the National Transitional Council (NTC) as well as being in charge of its oil, finance and economy affairs.

Prior to the revolution he was senior economic and financial advisor to the Libyan National Economic Development Board (NEDB) and senior economic advisor to the National Oil Corporation (NOC). He was also professor of economics at both the Western Mountain University in Gharyan and the Academy of Higher Studies in Tripoli.

In an interview with Libya Herald, he says that in parallel to security the new government must pursue economic reform in order to give young Libyans a stake in society. He suggests too, that as part of that reform and a spur to development, income tax could be abolished. But for any government to work, he insists, it has to be based in Tripoli. He says too that Libya will need foreign help.

By Michel Cousins.

Tunis, 4 September 2015:

Dealing with security will be a major challenge for the new Government of National Accord (GNA), says Mustafa El-Huni. But security is not a single cohesive issue. There is the matter of ensuring security in Tripoli so that the government can operate safely, plus the separate matters of the crisis in Benghazi, dealing with the Islamic State (IS or Daesh), and ensuring secure borders.

The first, El-Huni believes, can be achieved but will depend on two things: the backing of all the main parties to Libya’s crisis, and international support.

He believes that support from the GNC for a GNA will be forthcoming because the majority of the GNC in fact support the UN-brokered Dialogue. Moreover, the GNC it will be represented in it. That will open the door to security in the capital, he says.

There are those opposed to it, he adds, but they should give the GNA a chance to work. “We need to convince them to at least stand aside and see what it does.” If possible, they should be brought into it as wel, he says.

There may be some who still oppose an agreement, he adds, but with the vast majority of Libyans and the international community backing it, “they will be isolated”. As a result, he believes, they “will review their situation”.

Security in the capital, however, would still need a semi-military force which the GNA would have to create. There may also need to be international security support in the form of training and advice. One thing he strongly counsels against is a Baghdad-style Green Zone in Tripoli. It had not helped in Iraq and it would not work in Libya.

But “the government has to be in Tripoli,” he says. Otherwise it cannot operate. “If all parties agree to a GNA, it will be there”.

As to security in Benghazi, it would be more difficult given that the fighting is house-to-house. “We need a special force for this,” he says, indicating that there may need to be assistance from other countries, Arab and non-Arab, in dealing with it. But an immediate tactic has to be ending the flow of ammunitions and weapons to the militants.

“While the flow continues, there will be no solution.”

Sirte, on the other hand, being an open area, should be more easily dealt with, but it needs a unified military operation. “The number of IS people in Sirte is limited. If we have a unified army, we can deal with Daesh.” The problem, he points out, is that Libya, at present, does not have a unified army. The only working army structure is in the east, El-Huni notes.

Other than security, the new government has to immediately work on two other tracks, he says. There has to be a national reconciliation process and, alongside it, economic reform and investment.

For example, the GNA needs to move very quickly to repair damaged infrastructure, such as roads, ports and airports. That will create jobs and help get the economy going again.

In addition, “we need to create opportunities for young people, not just in the army and security, but in enterprises,” El-Huni insists.

Economic reform and unravelling the over-centralised bureaucratic state system will, moreover, help in solving security problems, he says. “With high unemployment and delayed salaries, there are no economic opportunities for young people. They have no alternative but to attach themselves to militias.”

As part of those reforms, there need to be loans to people to set up businesses. It has to happen as soon as possible, he stresses, adding that it could also be that such loans are linked to handing in weapons.

Another reform that needs to be looked at involves the overbearing tax system. “We don’t need a strong tax regime,” he explains. “In the GCC [the Gulf Cooperation Council states], there is no income tax.” It helps development there and instead of tax, companies pay licence fees. “We maybe need to look at this.”

Subsidies, costing between LD 10 billion to LD 12 billion a year, also need to be reviewed and probably abolished, he says, adding that it would certainly stop much of the smuggling.

Instead, salaries should be raised. “We need to pay a proper wage to all Libyans.”

As to the idea that, as a result of 42 years of Qaddafi rule when Libyans were paid just enough to keep quiet while foreigner labour was brought in, they had lost the work ethic, he points out that Libyans outside the country work hard and are productive. “The Libyans system is the problem, not the Libyans.”

But if economic reform is the “gate” to solving the country’s problems, it does not mean neglecting political and social issues. Moreover, changing Libya cannot be achieved in just one or two years – the latter the maximum time a GNA will have under the Libya Dialogue plan. “It is not long enough,” El-Huni feels.

It is enough, however, to make a start and to convince the Libyan public that it is going in the right direction, he adds. [/restrict]