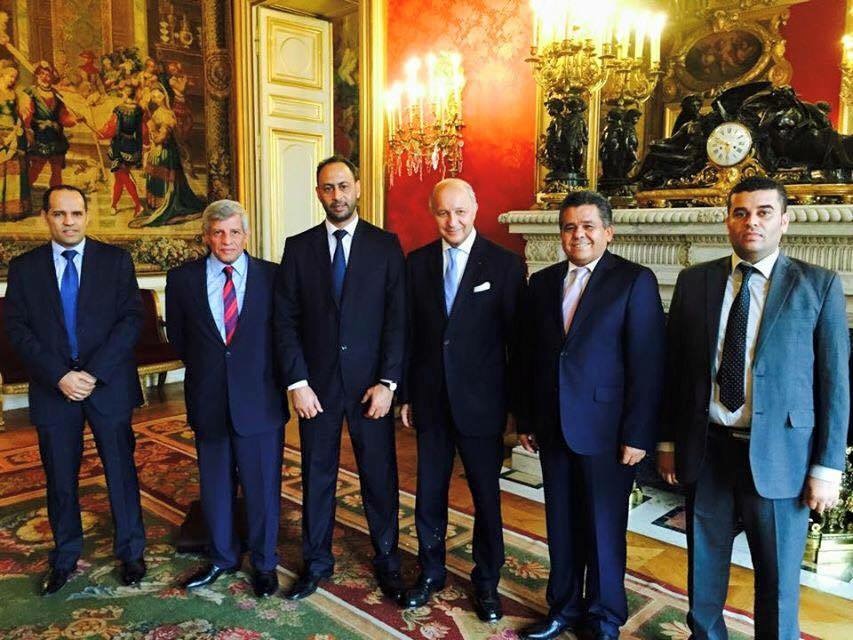

Mustafa Rugibani, currently Libya’s Ambassador to the . . .[restrict]Vatican, is one of the more than two dozen candidates being considered by the House of Representatives (HoR) to be their nominee as prime minister in the new Government of National Accord.

Previously Minister of Labour in the government of Abdurrahim Al-Kib, he had been a member of the National Transitional Council, heading its telecoms and transport committee. Prior to the revolution, he was with IBM in Paris, then set up and managed UBM, an IBM business partner in Jordan, and, from 2006 to the beginning of the revolution, also an IT company, MTS, in Libya.

Firmly convinced that the General National Congress(GNC) in Tripoli will rejoin the UN-brokered Dialogue process and approve the new administration, he spells out in an interview with the Libya Herald what the priorities for any new government should be.

By Libya Herald staff.

Paris/Rome, 25 August 2015:

Whoever leads the new government, says Mustafa Rugibani, it must deal urgently with a list of crucial matters – political, social and economic. Quite apart from the dominating issue of security, it will, he emphasises, have to ensure that salaries, pensions and allowances are paid, that schools reopen, that the health service functions normally again. In addition, there will have to be economic reform to enable Libyans to start making a living for themselves. As part of that, development targets will have to be set. The issue of illegal migration, too, will have to be tackled, as will pollution. In all this, Libya will be looking to its friends, regionally and in the wider international community, to help.

Security is a double issue. There is the country’s military divide and the need for the new government to safely operate in Tripoli; and there is the battle against the Islamic State (IS or ISIS).

In regard to the first, he is optimistic but the second will take more time.

“I expect the militias will cooperate with the new government and move their forces outside of Tripoli and allow the military to move in to secure the area for the newly internationally-recognised government.”

That is because, despite pressure from hardliners within the GNC and some of the militias, the majority of GNC members want to sign a peace deal, Rugibani says.

“I talk to them almost everyday. They want an agreement.”

There is mounting pressure on them, he points out, not just from the international community but locally in Tripoli. Residents are facing electricity cuts, shortages of food and cooking gas and other necessities. “Everyday more and people are turning against them,” he notes.

The GNC knows there is no other solution, that it has to sign, he says.

The alternative is that the militias in Tripoli will have to be removed by force. “That means bloodshed. I don’t think that will happen” because so many who were with the opposition to the HoR – Misrata, in particular, as well as the Muslim Brotherhood – now want a deal.

Even so, the UN and the international community must keep up the pressure on the GNC, he insists, “to make them sign the accord . . or the new government cannot go to Tripoli and the matter of the militias will not be resolved.” And, he stresses, “the government has to go to Tripoli. For it to be effective it must operate from Tripoli. There’s no question about it.”

Getting the country back to work is another major factor in ensuring security, says Rugibani. Paying salaries and allowances is part of that, but so too is economic reform. Without it there can be no change.

“The outgoing government did very little on the economic front because it was preoccupied with the security situation. As a result unemployment increased and young people had little option but to join the militias”.

The new government must focus on this, Rugibani says.

“It must launch economic programmes that will create jobs and encourage young people to start up their own businesses,” he stresses. And for that to happen will require the active involvement of the banks. “They will need to provide startup loans, guaranteed by the government.”

There should be incentives, too, to encourage Libyan businessmen to invest more and create jobs. One particular way of growing the private sector would be to give it priority in government tenders. But at the same time, he adds, foreign companies need to be incentivised to return and finish projects that they had already started, and to start new ones. They too need to be encouraged to create jobs for Libyans.

Libyans too have to change their work ethic, the former Minister of Labour says. “They cannot continue depending on Tunisians and Egyptians to do the work. It’s not normal.” Yes, he says, there will still be work for some of them, but instead of depending on the government [for handouts] Libyans have to start doing the jobs they are currently doing. The work ethic lost in 42 years of Qaddafi’s rule, when he paid people to do nothing because he did not want them to do anything or think for themselves, has to be recreated.

Libyans have to depended on themselves – and the government has a role in that, by creating skills training and funding. “They have to get involved in construction, they have to work in hospitals,” he says. “We have to build our own roads, our own schools and clean water supplies. Libyans have to do this. Libyans have to start working. Because if they don’t, if they stay idle, they will create problems – social problems. We have to create jobs for Libyans. They have to need to take ownership of the country.”

As for those young men in the militias who want to stick with that way of life, he says, they need to be able to sign up for the army or the police force.

But there too, there has to change, he says. The armed forces need to be reorganised and restructured from the top down. It is not a coherent force at present. The official army in the east and that in the west is split, he claims, not only between those linked either to the GNC or the HoR but also been those supporting the latter. He says out that he keeps in touch with the operations room in Zintan and that there is very little cooperation between it and the General Command in Marj.

This inevitably affects the battle against the Islamic State. “I believe ISIS will not be removed from Libyan soil [simply] through airstrikes.” There has to be an effective army on the ground to do the job. But “the army personnel are not effective on the ground to deal with such a force.” It needs to be restructured, re-trained and re-equipped, he insists. “My view is to lift the UN weapons embargo and equip our army. Then, and only then, we can have a joint international coalition fighting ISIS.”

Illegal immigration is a major issue not just for Europe but for Libya as well, he points out. “In some parts of Libya this became a source of income for some individuals. This can be handled with the right government in place.” To tackle the issue will require “strong coordination” between the ministries of interior and justice. “We also need the involvement of the original countries from where these immigrants came from.”

Europe too must also help “by giving support to our government in the control of the borders and make special programmes to help immigrants return to their countries and accept those who cannot.”

Rugibani says he firmly believes a new government will be created, that it will be installed in Tripoli and that it can turn the tide in Libya.

He is optimistic, he says, not least because the GNC will be represented in the new government. The GNC will sign and guarantee that the militias pull out, he predicts. But if the government has problems with one or two groups [that refuse to accept the agreement], they will have to use force against them,” he states. “I do not have any worries about political figures trying to spoil our newly internationally-recognised government. If so, they will be dealt with by their own parties,” he adds.

The grounds for a fresh beginning are there. “The Libyan people are tired of all the killings and kidnappings; morale has slumped.” Everyone is affected by the problems. Moreover, “all Libyans now understand that Libya will not be governed by one man or one tribe or one city”. He says he is optimistic.

“Assuming we will get a prime minster and a good team of cabinet ministers who would work as a whole via the parliament,” he believes the new government will be able to start on the changes the country needs. [/restrict]