By Michel Cousins.

Founded in May 2012, the Taghyeer Party (Party of Change) has no members in the General National . . .[restrict]Congress. That is because it took the decision not to stand in the Congressional elections two months later, saying that it would only enter the fray once a proper constitution was in place.

Today, despite a public wariness of political parties because of the perception that Congress has been prevented from delivering meaningful change as a result of the hostility between the two major parties there, Taghyeer is growing. It has around 6,000 members and 16 branches, from Tobruk in the east to Zwara in the west, as well as two in the south (Sebha and Brak). It is preparing to open more, again in the south and in the Jebel Nafusa. Its 37-member leadership committee similarly has members from all over the country.

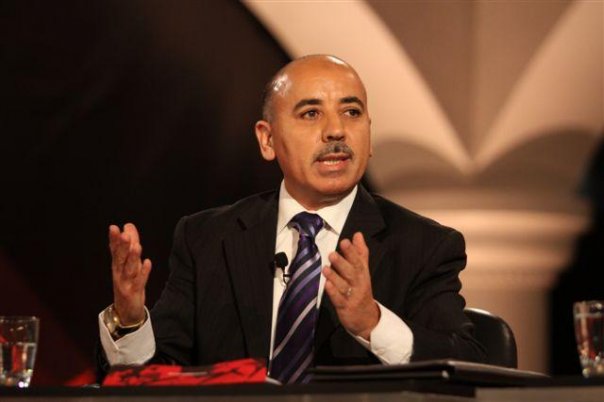

It is headed by Guma El-Gamaty who started his life in politics by becoming involved in 1976 in anti-Qaddafi movement in the UK, a year after arriving as a student. At the time, it was a life-threatening occupation.

He speaks about his and his party’s vision for Libya.

“I aspire for a country that is united politically, but which respects and accepts its ethnic and cultural diversity. I aspire for a society that respects work, that is patriotic; a society that adheres to the rule of law; a society that believes in democracy and respects human rights, that is proud of its heritage and culture, an important part of which is Islam – an Islam that is tollerant; a society that projects the true nature of Islam, which is moderate and non-extremist – in either direction”, El-Gamaty says in an interview at his party’s headquarters in Tripoli.

But putting that fundamental vision in practice will require perseverance, he explains.

“It is very important to achieve the transition to democracy. Even if it takes years, even decades for it to happen, it much be achieved.”

Libya must have a system that respects pluralism, he says – a system that “respects elections and what the ballot box gives us; a system where those who are elected regularly go back to the electorate for a fresh mandate”.

But the new Libya cannot be simply about ballot boxes. “We need transparency, accountability a free press and a thriving free civil society. Democracy is not just about elections. It is about the institutions of state.”

His personal preference is for a parliamentary democracy. “We cannot go back to a presidential system were one person has all the powers. For 42 years it was a very painful system.”

But whatever the democratic political system, “it is important that it works with our culture”. Libya cannot simply adopt a system from elsewhere. And whatever the system, there have to be checks and balances – “because no one person, no one group must have hegemony over the rest of society”.

El-Gamaty certainly does not believe that a return to three-province federal system would be in Libya’s interests. He does, however, firmly support decentralisation, in which local municipalities, grouped into regional areas, would be directly accountable, and with their own budgets which would be centrally audited. This three-tier system of government – national, regional and local – would, he believes, address the federalists’ complaints about marginalization.

In any event, “more money has to be spent on the peripheries that have been ignored – especially those near oilfields where people see the wealth pouring out and nothing coming in”.

That said, Libya’s national resources “must be administered by the central government”, he insists.

A free market economy

Economically, he wants to see a flourishing, free private sector and a diversification away from reliance on oil.

“Libya is a rentier economy” where oil and gas account for 98 percent of GDP, he explains. This does not encourage genuine growth, he stresses. It is crucial for Libya, he says, to develop other areas of income.

“The country needs to become a knowledge-based economy. The reliance on oil and gas must reduce.”

It is not just because such over-dependence is potentially dangerous. It also because it does not create the jobs that are needed. Only through diversification can a huge number of opportunities for young people be created, he explains.

Tourism, agriculture, a transit hub, the service industries, IT, the huge potential for solar energy – these are where he sees the Libyan economy of the future, and where the investment has to take place.

“This can only be produced by a totally free private sector. The state must be rolled back from many [economic] activities. We need to unleash the private sector to achieve growth.” In particular, there has to support the growth of SMEs. “We need to encourage a culture of innovation and entrepreneurship.

Nonetheless, the rolling back will have to be gradual, he believes.

It must start with privatisation.The banking system is one area where this has to happen early. As part of this, he would like to see foreign banks opening up in order to promote competition. Libya could, he believes, become as a major regional banking centre like Bahrain.

Other companies must come too. “It is important to allow international companies to come to Libya to set up joint ventures and partnerships. It will increase the quality of products and services. It will allow for knowledge and expertise transfer.”

Libya has so many advantages that it should use, he points out. Its geographic location is there to be used to advantage – as a tourist destination, a gateway to Africa and close to Europe. Being in the middle of the Mediterranean has so many advantages that can be exploited, he says. Moreover, the country has many natural resources. There are minerals – gold, iron, copper, and even uranium. “Mining offers a huge potential for growth in Libya.”

In all this, the government has to take on the role of an enabler. But that does not mean that it pulls out altogether from the economy. “The state has a role in major projects”. He cites petrochemical projects and solar power as examples.It will require major legislation. For the banking industry to succeed, for example, currency controls must go. They serve no purpose other than restrict growth.

“The first genuinely elected parliament after the constitution [is enacted] should unshackle us form all the bad Qaddafi laws”.

Empowerment of Women

El-Gamaty points out that there are more young Libyan women than men at universities and colleges, “yet they don’t hold middle or high ranking positions in the country”. He points out, too, that they played a major role in the revolution. They have to be recognised as equal partners in society. “This may take some time,” he admits, “but we must work on it.”

There is nothing to stop it. “There are no religious grounds to prevent women’s empowerment, including political participation. There is no contradiction with our conservative religious values or the fact that the family is the cornerstone of society.”

Politicians should lead the way, he believes. “Women in parliament are an essential component of achieving the overall development in Libya”, he states. “Political parties themselves must take the initiative by putting women in key positions. We in Taghyeer are behind but must meet the challenge.”

A Maghreb Economic Union and closer ties across the Mediterranean

For the new Libya there is a new role awaiting it in the world. Regionally, El-Gamaty wants to see much more integration within North Africa – the Maghreb. “There is a synergy with Tunisia and Morocco” to be built on, he says, which can see the region developing into its own version of the European Union. Furthermore, that version should develop strategic links with the EU.

So too, in the meantime, must Libya – and certainly, he adds, it must do more to end the illegal immigration trail that uses the country as the Mediterranean crossing point to Europe.

“I aspire to the day where Libya is trusted as a stable democratic country and Libyans are free to travel to the EU without visas,” he declares with passion.

After all, he points out, Libya is a Mediterranean country. “Libya should also look north and develop much closer relations with its Mediterranean partners on the northern shores.”

Not that this means neglecting Africa. “It offers huge potential,” he insists. “Libya needs to invest in Africa – and support reform and democratisation there”.

A learning curve

“The transition is tough,” El-Gamaty says, referring to the current lack of security and the political instability affecting the country. “But we have no alternative,” if the country toes emerge as the vibrant and economically successful democracy that he aspires to.

It is on a learning curve, he states – politically, economically and socially.

The problem is Libyans have for so long been shut away from the world. In particular, education is very poor. It has affected the way people think and react, he explains. For example, creating jobs and diversifying the economy are one thing, he notes. But getting people to respect work again after the decades of Qaddafi actively destroying a sense of responsibility is another.

There has to be capacity building. “It is a key element in our vision,”

The reason why a country such as Tunisia, with no natural resources other than its people, is much more cohesive and developed is because it has a good educational system. Libya has to have the same.

Another challenge is that Libya has a small population fragmented over large areas. “It needs to become more cohesive”.

There is so much to unite rather than divide. Noticeably, he enthuses about Misrata which he sees as becoming the commercial capital of Libya. “Why knock it?”, he asks. “Misrata is an opportunity for Libya. It’s one of Libya’s great strengths. They are great entrepreneurs” he proclaims, “They aren’t separatists.

“I believe that when we have a constitution and a strong state, Misrata will hand in its weapons. It wants stability, accountability, transparency, the rule of law and strong state institutions. These are thing that it and all business communities want.”

A pursuit of a more cohesive country is where his faith in the value of political parties and civil society organisations springs from. “They bring people together based on a common vision, not on a tribal district.”

But El-Gamaty is well aware that political parties are not popular at present. “A lot of people blame the failure of General National Congress on the two parties [Justice & Construction Party and the National Forces Alliance] fighting each other.

If, as increasingly seems possible, there is an election for a second interim Congress before the Constitutional Committee comes up with its draft constitution, he thinks that parties could be excluded from the contest. “We expect people to demand that political parties step back”. Congress, he thinks, may pass an amendment to the 2011 Constitutional Declaration allowing individuals only to stand for its replacement.

But even if that is not the case, Taghyeer will likely not stand. “We will only compete in a system after the constitution [is enacted] in which parties can compete.”

He adds: “You cannot have a pluralistic system without parties.”

In any event, he thinks it is entirely possible that the Constitutional Committee will not come up with a draft within the allocated four-month timespan.

“It could possibly take much longer and we should allow the needed time for Libyans to achieve consensus on the new permanent constitution.”

This is the first of a series of interviews with leading Libyan figures about the vision for the country. Next: Dr Mustafa Abushagur [/restrict]