By Mustafa J. Salem

Tripoli, 11 October 2013:

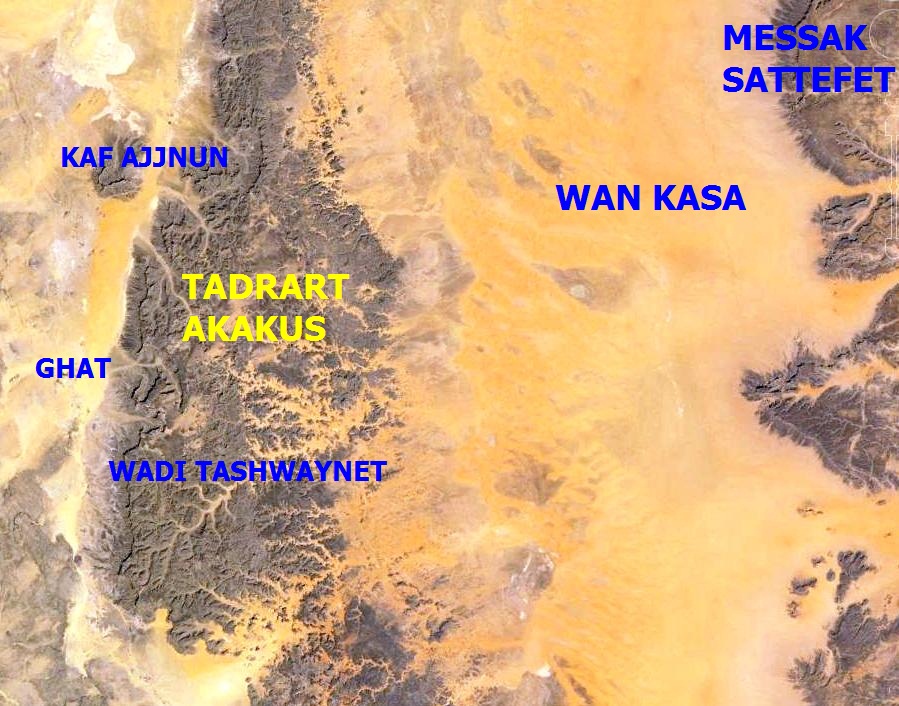

Located in the Sahara Desert in the Ghat district of southwest Fezzan, Libya, Tadrart . . .[restrict]Akakus is one of the most famous rock art areas in the Sahara. This beautiful area which, besides its extraordinary natural beauty, is very rich in prehistoric paintings and engravings was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1985 (Figures 2, 3 and 4).

A succession of rock art, including cave paintings and carvings of various styles are scattered throughout the valleys.

In some of the desert heritage areas (including Tadrart Akakus), it was possible for experts to distinguish various periods, corresponding to successive climatic phases which brought about changes in the flora and fauna and, thus, in the ways of life of the local populations. These variations are characterised by particular artistic styles which were classified by archaeologists so as to help relate these paintings and engravings to a particular time and environment as well as to the social life of the inhabitants in each period.

The oldest images in the Akakus area belong to the Wild Fauna Period. These images were created when the Sahara was covered by savannah, and elephants, rhinoceros and giraffes were found in the plains along with many other wild animals. Images of these wild animals were carved on the scarp faces in this area.

This period was followed by paintings and engravings which include various human figures and is known as the Round Heads Period. The Pastoral Period followed, during which the climate of the Sahara became more arid. Depictions of domesticated cattle and social festivities with human figures dominate this period (Figure 3) which was followed by the Horse Period that refers to paintings mostly depicting horses and chariots (Figure 4).

The final period is the Camel Period which dates from about 200 BC to the present, during which the Sahara finally became the arid desert that it is today (Figure 7). In this period the Tuareg and Garamantes people adopted this earlier tradition of paintings and engravings and created their own images.

Introduction of the extensive prehistoric rock art in this important area to the general public as well as to the scientific community worldwide is credited to the Italo-Libyan archaeological missions, which have run continuously from 1955 in Tadrart Akakus under the guidance of Prof. Fabrizio Mori and Paolo Graziosi. Through the years, Prof. Mori and his associates from the University of Sapienza in Rome collected, analyzed and published a large amount of scientific information.

Topographically, the Akakus Mountains have widely varied landscapes formed mainly of hard sandstone beds that date back to the Palaeozoic era. The weathering and erosion of these clastic beds have resulted in a variety of terrains and features. These include deep wadis, natural arches, caves, gorges, isolated hills, and towers emerging from the sand and eroded into the most bizarre shapes. These landscapes have enabled the inhabitants throughout history to live in shelters and caves, most of which have paintings of various types and sizes. The mountainous ridges are also separated by sand dunes, wadi deposits and some Hamada plains (Figures 2, 5 and 6).

Current Concerns

Unfortunately, this beautiful and most important World Heritage area has been recently vandalised, and the resulting damage is yet to be rectified but may be so bad as to be beyond restoration.

It was in April 2009, when several rock art sites in two of the main wadis in the famous Tadrart Akakus, including some of the most well-known and highly acclaimed images, were vandalised through the application of spray paint. As there were no guards or security personnel in the area, the attacker took his time to commit his crimes and left without being caught.

The episode began when an employee of a tour operating company was sacked and sought revenge. He travelled to the Akakus Mountains, where thousands of paintings and engravings are scattered in shelters and on ledge faces. He sprayed several sites with black and silver nitro paint before heading back home. Though he was caught at a later time the damage he inflicted remains and in many instances is beyond restoration.

Ten months later (February 2010) the authorities submitted a written report on the vandalism and the damage caused by it to UNESCO. The report summarized the damage by saying: “Seven distinct sites are known to have suffered ‘very high to high’ levels of physical damage with black and silver nitro paint sprayed onto the images, either entirely covering them or partially covering them with graffiti. In some cases, such as at the Ti-n-Asching II site (among the best known in Saharan rock art in the Horse/Bi-triangular style), the nitro spray paint completely covers all the rock art scenes”.

The report concluded by urging the Department of Antiquity, in collaboration with UNESCO and the University of Sapienza in Rome to undertake a detailed assessment, so as to specify those sites that might be capable of restoration.

It was also emphasised that the mission must stipulate the future protection of Tadrart Akakus. Since it is a very extensive area, it was recommended that collaboration with the local communities should be seriously considered. Tourist operators should also be made aware of the sensitivity of the area and the global significance of its contents, and an effective system of issuing tightly controlled permits regulating visits to the area must be established.

An official visit to the area was conducted almost a year later (in January 2011), just before the revolution in Libya.

As part of this official visit ten of the vandalised sites were surveyed and their condition and physical context systematically recorded and analysed. For each site, information was obtained on the morphology, conditions of the site, size, dating indicators, iconographic symbols displayed, nature of rock support, painting methods and materials, engraving methods and technologies, any alterations to the art itself or to the rock surfaces to which it is applied, as well as damage related to the recent vandalism. The site-specific analysis highlighted certain key observations:

- Damage to the ten studied sites is considerable, along with other damage resulting from natural deterioration of the artwork due to time (some paintings are 10,000 years old).

- Due to variability in substrate conditions, artwork materials and remedial technologies to be used, it is suggested that efforts to test cleaning agents on the vandalized sites will need to be adjusted to suit the particular conditions of each site, and each site element.

- Any conservation strategy for the artwork should be applied to all significant artwork not only to the artwork damaged by vandalism.

The mission report proposes detailed methodologies for conservation-restoration interventions on the paintings and engravings, and for cleaning and restoring the vandalised sites.

What next?

From the mission report summarised above, and the sequence of events regarding the status of Tadrart Akakus (this example also applies to other heritage areas in Libya), it was very clear that the area was neither adequately protected nor properly managed. The report calls for the authorities to make their presence felt, for staff to be well trained and to build the capacity to man and direct the large area of the Tadrart Akakus.

With the formation of the Ministry of Culture, it is essential that this new ministry place the preservation of Tadrart Akakus, Messak and the remaining desert heritage sites at the top of its list of priorities. Restoration and preservation of the desert heritage ae already long overdue. These areas will need a massive effort, time and resources in order to halt – at least for the time being – the deterioration of these national heritage areas which is important not only to Libyans but to the whole of Humanity at large as is recognised by UNESCO.

With desert tourism currently halted, it provides a wonderful opportunity for the Ministries of Tourism and Culture to collaborate and coordinate efforts to establish as a matter of urgency a National Heritage Protection Master Plan with the main objective of preserving all the national heritage areas, starting with those desert areas that are the most impacted.

The oil companies operating in the area should also play an important role in implementing this National Heritage Protection Master Plan. Since these oil companies are at least partly responsible for some of the detrimental impacts on the heritage sites, it is in their interests to help sustain these areas in which they have been working and will continue to do so for years to come.

Meanwhile, the help and cooperation which is always offered by international organisations, scientific institutions and individual scientists should be used – and used efficiently – by the relevant authorities in Libya, especially the Ministry of Culture (including the Antiquity Department) and the Ministry of Tourism (Figures 5, 6 and 7).

Local communities will be eager to play a role in these operations as they are aware of the importance of these areas and their heritage not only to their local community but to the country as a whole.

Until the authorities act and begin the actual restoration and preservation, however, the deterioration of this priceless heritage will continue. This will render restoration efforts even more difficult.

[/restrict]