By George Grant.

London, 11 November:

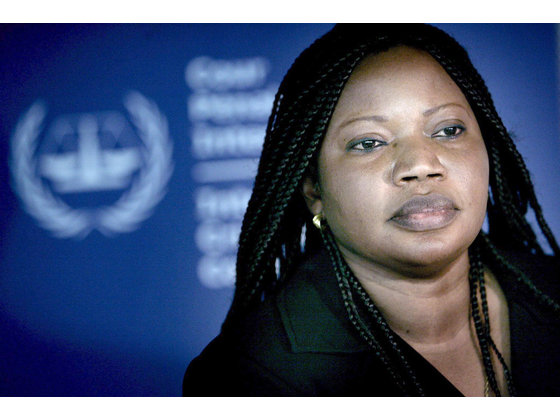

The ICC may be preparing to bring fresh charges for crimes allegedly committed during last year’s revolution, . . .[restrict]Chief Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda has said.

On Wednesday, Bensouda presented the UN Security Council with the fourth ICC prosecutor’s report since the onset of the 2011 revolution, in which she announced that a decision would be taken “on the direction of a possible second case in the near future”.

Amongst the possible crimes being investigated are allegations of rape and sexual violence, which targeted both men and women; allegations against other members of the Qaddafi government for crimes committed during the events of 2011; and allegation of crimes committed by revolutionary forces, including against the residents of Tawergha, non-combatants, and against detainees.

At present, the ICC has active cases against Saif Qaddafi, eldest son of the former dictator Muammar Qaddafi, and Abudullah Al-Senussi, his former intelligence chief. Both men are being investigated for alleged crimes against humanity committed during the 2011 conflict. The case against Muammar Qaddafi was dropped following his death last October.

Allegations of crimes committed both during the conflict and subsequently have been widespread, with rights groups including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International presenting a number of reports providing fresh evidence in the past 12 months.

To date, however, only a handful of the thousands of detainees being held in prisons and detention centres across Libya have been brought to court, and fewer still prosecuted. It is believed that many people involved in serious crimes also remain at large.

Any new charges that are brought by the court will have to be extremely serious, as the ICC is only mandated to investigate crimes of the gravest concern, namely war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide.

The ICC is also specifically designed as a court of last resort, meaning that it will not act on any case unless the national judicial system in which it would ordinarily be heard is deemed either unable or unwilling to do so itself.

At present, Tripoli already presented a challenge to the admissibility of the ICC case against Saif on the grounds that he can now be afforded a free and fair trial inside Libya, and the court is due to deliver its verdict on that challenge shortly. The ICC expects to receive similar challenge to the admissibility of the Senussi case in the near future.

Because the ICC has no mechanism whereby it can force states to handover suspects wanted for trial, it is highly unlikely that any of these cases will reach The Hague given Libya’s commitment to handling the cases itself.

Bensouda’s predecessor as ICC chief prosecutor, Louis Moreno Ocampo, recognised this dilemma and repeatedly hinted at a compromise option with regards to the Saif case, whereby the trial would take place inside Libya, but with support from the court to ensure that international standards would be met.

Bensouda herself also appears to be seized of this reality, admitting recently that any attempt to enforce an ICC decision that Said should appear before The Hague “would be difficult”. [/restrict]