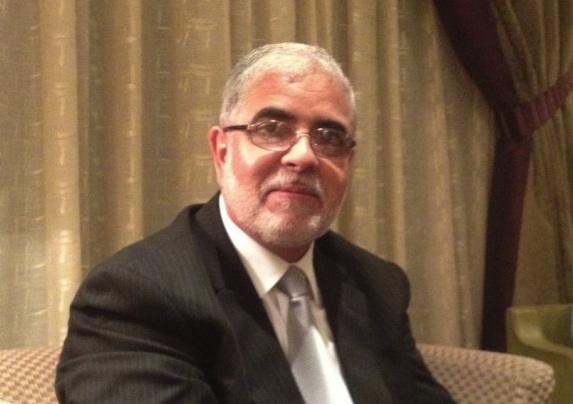

By Michel Cousins.

Tripoli, 7 September:

Deputy Premier Mustafa Abushagur is one of the three front-runners to become Libya’s next Prime Minister. The . . .[restrict]vote in the General National Congress is expected to take place on 12 September.

His CV itself makes for remarkable reading.

Born in 1951 in Suq Al-Juma, now a suburb or Tripoli, but then a village well outside the capital, he moved with his family to Ghariyan as a child and then returned to Suq AL-Juma for schooling. He went on to the University of Tripoli to study electrical engineering.

In 1975, he moved to the US to study at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) for his MSc and then a PhD which he gained in 1984. Refusing to return to the Libya of Muammar Qaddafi — he soon became involved in Libyan student opposition politics in the US — he became an academic, first at University of Rochester in 1984 then in 1985 at the University of Alabama in Huntsville where ten years later he became the Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering. There he made his mark as a world-class optical engineer. It resulted in hisworking for NASA on the US space programme, the US National Science Foundation, the Federal Aviation Authority and the Department of Defense. Later he established two optical companies and the PhD Program in Microsystems Engineering at the Rochester Institute of Technology. He set up and became president of RIT’s campus in Dubai in 2008. He has written extensively of optics, including some 100 academic papers.

After an absence of 31 years, he returned to Libya in May 2011, to Benghazi where he became an adviser to the NTC. He was appointed Deputy Prime Minister last November.

At the moment, there is a deadlock between the three leading candidates — Abushagur, former prime minister Mahmoud Jibril who heads the National Forces Alliance which emerged triumphant in the party list in the July elections, and Electricity Minister Awad Barasi, the candidate of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Justice and Construction Party.

Abushagur sees himself as the candidate who can unite the country unlike the other two front runners. “I’m the candidate that can break the deadlock”, he said in an interview with the Libya Herald.

He says he would head a government of national unity, appointing ministers from across the party spectrum.

Asked whether any members of the present government would remain in office, he says “very few”, although that indicates that some would. Perhaps that is because, he says he feels that there needs to be continuity with the policies of the present government,

For him, the private sector is a key to rebuilding the economy. “We must have a free market”, he says. He would positively encourage it. He also wants to make Libya more accessible to outside investors and technology. “We are still in the fax age”, he says. He wants to change the regulatory system, cut red tape and bring Libya up to date. He also says he wants to end subsidies.

For him, security is the priority. “We need to take weapons off the streets”, he says. But this should not be achieved by simple force it. Young people with guns are frustrated because they do not have job, he points out; security and jobs therefore go together. “We have to give opportunities to young people”, he says. The government needs to enter into dialogue with Libya’s youth to address the problem. They have earned the right to be consulted, he says. “They were willing to give their lives” for a better Libya. As such, they have already been part of the solution to Libya’s problems.

The other priorities for a government that will, at most, have tenure of only a year and a half, are government services — he highlights health, education and transport infrastructure.

The government will also have work for reconciliation, he believes. “But there must be justice too” he adds.

He does not mention Saif Al-Islam, Abdullah Senussi or the other leading Qaddafi regime figures Libya wants to put on trial, but he was speaking to the Libya Herald on Tuesday, the same day that a Libyan ministerial team had flown to Mauritania to bring Senussi back to Libya. Abushagur has been central to this. He has led the moves to get Qaddafi’s intelligence boss extradited and brought to trial.

One of the major problems the present government had with the former National Transitional Council was that it would vote for a policy without discussing it with the government, which would then be left to implement it —such as the payments to the revolutionaries or the LD 2,000 to families to celebrate the first anniversary of the revolution. The NTC effectively acted as if it were the executive and the government its private secretary. Might not the same happen with the new congress and new government, the Libya Herald asked Abushagur.

The NTC “did not understand the difference” between the legislature and the executive, Abushagur says; it thought it was the executive.

The new government, he says, will have to work closely with the Congress to prevent any reoccurrence of such behaviour.

Abushagur further believes that some of the laws passed by the NTC will have to be reviewed, such as that freezing the assets of certain individuals.

Land ownership is an issue that his government would tackle, he says. It is widely recognised that arguments as to who owns what, are going to be a block on economic development. Former owners are already claiming that they rightfully own major development sites.

The problem stems from Qaddafi’s 1978 Law Number 4 (Abushagur refers to it as the “infamous Law Number 4”) under which property was confiscated from so many Libyans, and given or sold to others. The original owners are demanding it back. In cases where the government became the new owner, some property has been returned. There also have been instances of property being seized back by force. The issue is, nonetheless, extremely complex. It will not be easy returning property in which other people have been living for years.

“Something has to be done, but we can’t just come and throw these people out into the street,” said Abushagur four months ago when asked about the issue. “We’re asking people to be patient. I lost property, too.”

There is now a sense that the issue has to be addressed as soon as possible. “We need to deal with it right away”, he says. But sensitively. The government, he believes, will have to negotiate between the rightful owners and those currently in possession to solve the problem “without creating other problems”. But other countries solved the problem, notably in eastern Europe after the fall of communism. Libya, Abushagur believes, can do the same.

The role of women is one that his government would safeguard, he says. Women have “equal right” in the new Libya. Like the youth of the country, they earned that right in the revolution. But this too is more than a right earned. He will not countenance the segregation being demanded by some Islamists. “We need every Libyan to be part of Libya”, he says, men and women. “Women must have their place; it is up to them to chose”. If they want to stay at home and not take job or get involved in their community, it is their choice. But if they want to play an active part in the life of the country, it is their right, he insists.

There are other issues that a government led by him would address. Libya has to ease its visa regime, he says; the country has to become more “accessible”. At the same time his government would not allow others to take advantage of it. Referring to claims that Gulf states may have been behind the recent attacks on Sufi shrines, he is firm: No interference in Libya’s internal affairs will be tolerated, “from wherever it comes”.

However, he is “very interested in working with neighbours”. This comes in response to a question from the Libya Herald as to whether his government would create close economic bonds with Tunisia that could be the basis of a wider regional economic zone. Yes, he says; he would like to see “a real strong relationship” with it. The two countries, he agrees, complement each other. He also mentions Morocco as a potential partner in such a tie-up.

As to his being a US as well as a Libyan citizen, the fact that the GNC has passed a law stating that the prime minister, as well as the ministers of Interior, Defence and Foreign Affairs, cannot have duel nationality, (nor can their spouses) is not seen as a probem. Asked, if elected, he will he renounce his US citizenship, he responds with a categoric “Yes”.

His policies seen highly pragmatic, but then Abushagur is an engineer and by training and occupation, engineers tend to be very practical, simply because they have to come up with solutions that work. Ideology, generally, is not for them.

He also comes across as confident, calm and thoroughly in control. Moreover, for someone who is both a deputy prime minister and one of the world’s leading optical engineers, he is very down-to-earth and approachable.

Indeed, at the Libya Herald he is sometimes known as a latter-day Haroun Rashid, the 8th-century caliph who would go in disguise into the streets of Baghdad at night to hear what people were saying. That is because on more than one occasion we have come across him at some event in Martyrs Square. He is there not in any prominent position but just another person among the crowd, mingling in with everyone else. Soon enough, he is buttonholed by a member of the public who has an issue to raise. We have watched as Abushagur listens — intently— and then calmly explains what can or cannot be done.

There are not many other countries’ deputy prime ministers and deputy presidents doing the same.

This is one in a series of articles on the candidates for the post of Prime Minister. [/restrict]