By Nihal Zaroug.

Tripoli, 6 August:

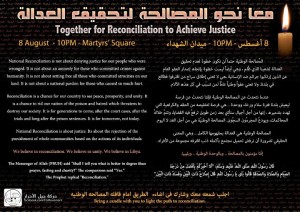

The Free Generation Movement (FGM) . . .[restrict]is organising a candle-light vigil on 8 August as part of an initiative calling for ‘thanks-giving’ and national reconciliation in Libya. It was earlier but erroneously reported as being organised by Lawyers for Justice.

The chosen date marks the 20th day of Ramadan, which last year coincided with the liberation of Tripoli. It is felt that it is a time when remembrance of the country’s sacrifices and those who have fallen is more than appropriate, and that the event will evoke a spirit of ‘mercy and forgiveness’.

The vigil will be held at Martyrs Square and will commence after Taraweeh prayers. It was originally conceived by activist Hafed Al-Ghwell, who saw the holy month of Ramadan as an opportune time to engage society in focussing on unity, thanksgiving and reconciliation.

“Ramadan is the month of forgiveness, mercy and sincere effort to be closer to the deeper values and meanings of Islam”, said Al-Ghwell. “It was on the 20th of Ramadan, the anniversary of the fall of Mecca, that Tripoli was liberated and the war in Libya started to end. It’s a day that spells reconciliation in every way.”

An advocate of universal human rights, FGM is a non-governmental organisation that has been active since the 17 February Revolution. It has various programmes aimed at bringing stability and development to Libya. It launched the No Gun Zone drive and most recently Voter and Election awareness campaigns. The movement also initiated both the Mafqood (Missing) and Shaheed (Martyrs) projects, which hope to play important roles in reconciliation in Libya.

Closure for the thousands of families of the missing or fallen will only come with acknowledgement of their loss, that truth-seeking is synonymous with reconciliation and that, as a nation, Libya cannot move forward until this occurs. FGM founder Niz, drives this point further by stating: “It is imperative to acknowledge that the missing are fundamentally encompassed in the scope of reconciliation and to insist that this issue is not subject to ideology or political affiliation. The families of the missing are our families, our missing and we will help them no matter who they are, where they come from and what their political and ideological background may be. This is essential for Libya’s future.”

The issue and importance of transitional justice and reconciliation has seen little government action, nor has it been at the forefront of the political debate. Very few parties and candidates spoke about it in last month’s elections, let alone campaigned for it. However, FGM has received public support from Deputy PM Mustafa Abushagur and NFSL’s vice president Mohammed Ali Abdallah, by confirming their attendance at the vigil. Niz says, “whilst we are delighted with their attendance, the most important thing is to demonstrate the will of the people and it is to convey a strong message of unity and hope through reconciliation and togetherness”.

Currently, Libya’s judicial system is not fully functioning and there is widespread concern that the government has dealt inadequately with the thousands of detained, missing or internally displaced individuals.

Several NGOs have made strong appeals to the government to take concrete actions but to no avail. Some of them fear that justice and reconciliation will continue to be in a state of limbo well after power is transferred to the newly elected National Congress on the same day as the vigil.

“The newly elected national assembly, and the provisional government it appoints, should not continue to delay reforming the justice system”, said Human Rights Watch said recently. “Libya’s leaders should also seek assistance from governments, the United Nations, and non-governmental organisations to address transitional justice.”

Many civil society groups believe that the terms human rights and rule of law are not uttered enough by government officials, that in the public sphere justice is often confused with vengeance and that, in the absence of a fully-functioning judiciary, matters are resolved by local elders or by force. They want the authorities to look elsewhere for concrete examples on how to develop an effective process of reconciliation. A number of African states, notably South Africa, have successfully developed post-conflict reconciliation programmes. The international experience with restorative justice and its focus on building a human rights culture has received much acclaim.

Through the vigil, FGM hopes that people will begin to debate and understand that “reconciliation does not deny the need for justice or the desire to bring to account those who committed atrocities. Reconciliation is the concept that rids us of hate and vengeance, which are characteristics that will prevent us from achieving true justice” as specified by Niz.

Various other groups have endorsed and supported the vigil and include the National Movement for the Empowerment of Women (NMEW), LES TEAM, Voice of Libyan Women (VLW) and Sabha Youth Forum. Libya Outreach Group and the Marboaa Discussion Forum have been key in the organization of the initiative.

Given the scale of the crimes committed during Libya’s revolution and the retaliation that is too often being ignored, an approach involving restorative justice could provide a “different way of dealing with human conflict and criminal offences, holding offenders responsible for the crimes, damages and harm inflicted upon victims, while focusing on restoring relationships after the crime has been committed”. This notion of justice is championed by leading sociologists who have studied criminal wrongdoing.

A year after the war ended, the people of Tawergha are still displaced and subject to reprisal attacks, and until a ceasefire just brokered in Kufra by local elders, clashes there between Tebus and the Zway community seemed unending. Community outreach programmes like its Tafaoul project are, say FGM, necessary to “educate society about tolerance and forgiveness, and ensure persecuted communities are cared for and not neglected.” As Niz puts it, “large-scale conferences and press conferences and public statements are well and good, but work on the issue of reconciliation needs to be done on the ground within our communities – at a grassroots level”.

Al-Ghwell cautions that Libyans today have a real choice to make. It is not an easy one “nor can it be based on emotions and slogans but on sober analysis and conscious decision to choose between the path of Iraq or the reconciliatory path of South Africa and Eastern Europe. If Libya does not start the hard work towards national reconciliation, the future will be very bleak indeed for all our other hopes”.

The vigil is viewed by many Libyans as a step in the right direction which could bring about the necessary debate and change needed for Libya to honour the undertakings of the revolution and move forward as a peaceful, united and democratic country.

For further details on the reconciliation vigil see event posting and for more on FGM visit their website.

[/restrict]