By George Grant.

Benghazi, 7 July:

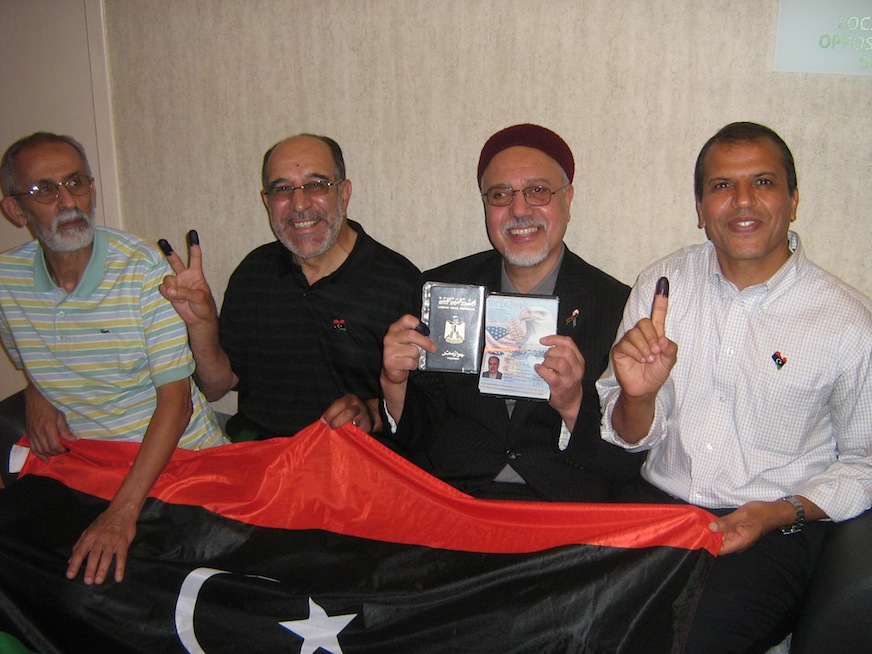

At a makeshift camp in a cement factory five miles out of Benghazi, a small group of . . .[restrict]Tawerghan refugees gather to cast their vote.

Compared with the scenes of jubilation being witnessed elsewhere in Libya, the mood here is decidedly subdued. A tattered UNICEF tent stands empty in the middle of the complex, whilst young men languish next to stalls selling food, cleaning products and other necessities nearby.

The 2,600 members of the camp were brought here last October by Benghazi revolutionaries who rescued them from Kufra, where they had fled following the collapse of Muammar Qaddafi’s regime.

Now, with the opportunity to vote, some of the camp’s occupants are hoping their fortunes may start to change.

“God willing, this election will make a difference”, said Salem Mohammed Ashour, a retired soldier who had just cast his vote. “Tawergha has some candidates standing and we hope they will be elected so they can explain our situation”.

At present, the situation of the country’s Tawerghans is far from sanguine, and the group must rank amongst the most reviled in all Libya.

During the war, Tawerghans were accused of committing horrendous crimes for the regime against the nearby city of Misrata, with instances of rape, looting and murder reported on a widespread scale.

Since then, Misratans have exacted collective punishment, forcing almost all of the 30,000 occupants of Tawergha to flee and burning the town to the ground. Many thousands are now being held in detention centres and camps across Libya, where instances of mistreatment and neglect are widespread.

Tawergha has four candidates standing in these elections, ironically as part of the Misrata constituency, and the camp’s residents say they will be voting for them and them alone.

“We want to help move this country forwards, and for Libya to understand that we are just ordinary people”, said Salem Ali, a spokesman for the Tawerghans who visits the camp every day. “We are talking to the government a lot, but they aren’t listening to us”.

Unfortunately, reconciliation between Tawerghans and other Libyans still seems a long way off. Viewed as murderers, rapists and Qaddafi loyalists by most of their fellow countrymen, bitterness continues to run deep on both sides.

“Many people will not be voting today”, Ali continues. Some of the women who’s husbands are still detained are boycotting the elections, and I myself am too angry to have considered standing as a candidate. We knew what it was like under Qaddafi, but we never imagined it could be worse for us in the new Libya”.

More than anything else, Tawerghans here say they now just want to return to their homes. “We don’t care if Tawergha has been burned down”, says one. “We will live under the trees if necessary”.

At present, such talk sounds like dreaming. A return to Tawergha would almost certainly risk further recriminatory violence, and here at least they are clean and safe. Most of the children are in schools and the biggest danger for the camp’s adult residents is ideleness, a fate that currently seems impossible to avoid.

With just 400 of the camp’s 1,400 registered electors having voted by the early part of this afternoon, it is also far from certain whether any Tawerghan candidates will be elected, still less how effective they will be in the new National Conference if they do succeed.

An effective justice and reconciliation process is badly needed for the Tawerghan problem, as it is for many other unresolved conflicts in the new Libya. With the transitional authorities having failed to put such a process in place, it will now be up to the new government to have the courage to take that initiative.

As things currently stand, the residents of this camp look set to be here for a good while longer yet.

[/restrict]