By Jason Pack and Ronald Bruce St John

Cryptic tweets from Al-Jazeera’s correspondent Omar al-Saleh suggest that over the . . .[restrict]past twenty days the deputy Head of the Libyan Election Commission, Sghair Majeri has repeatedly attempted to resign. Despite the completion of the voter registration drive — deemed successful by UN observers — it still appears likely that the elections scheduled for June 19th will need to be postponed due to mishandling of the preparations. Amazingly, even though the elections are less than three weeks away, the Election Commission has leaked news about a possible delay but is not yet ready to announce it officially. Many speculate that this is because if a delay were announced, the Commission is not yet sure it would be able to hold the elections by the new date. The current wisdom among Libya watchers appears to be that the elections will be delayed, but by less than a month so that they may be conducted prior to the start of Ramadan, and that the delay will be announced within ten days of the election’s original scheduled date.

While the Egyptians and Tunisians have both managed to hold their elections on time, the Libyans seem not even prepared enough to be able to delay their elections coherently. In short, true to form, uncertainty reigns in post-Qaddafi Libya.

But when Libyans do finally go to the polls they should not conflate their frustration with the National Transitional Council (NTC) or the Electoral Commission with a perceived need to bifurcate their country into semi-autonomous provinces, or even worse, boycott the electoral process — as some supporters of regional autonomy have threatened to do. Dangerously, the logical leap between upset with the current central government and calls for weakening the institutions of central governance is becoming one of the defining features in Libya’s post-Gadhafi political discourse.

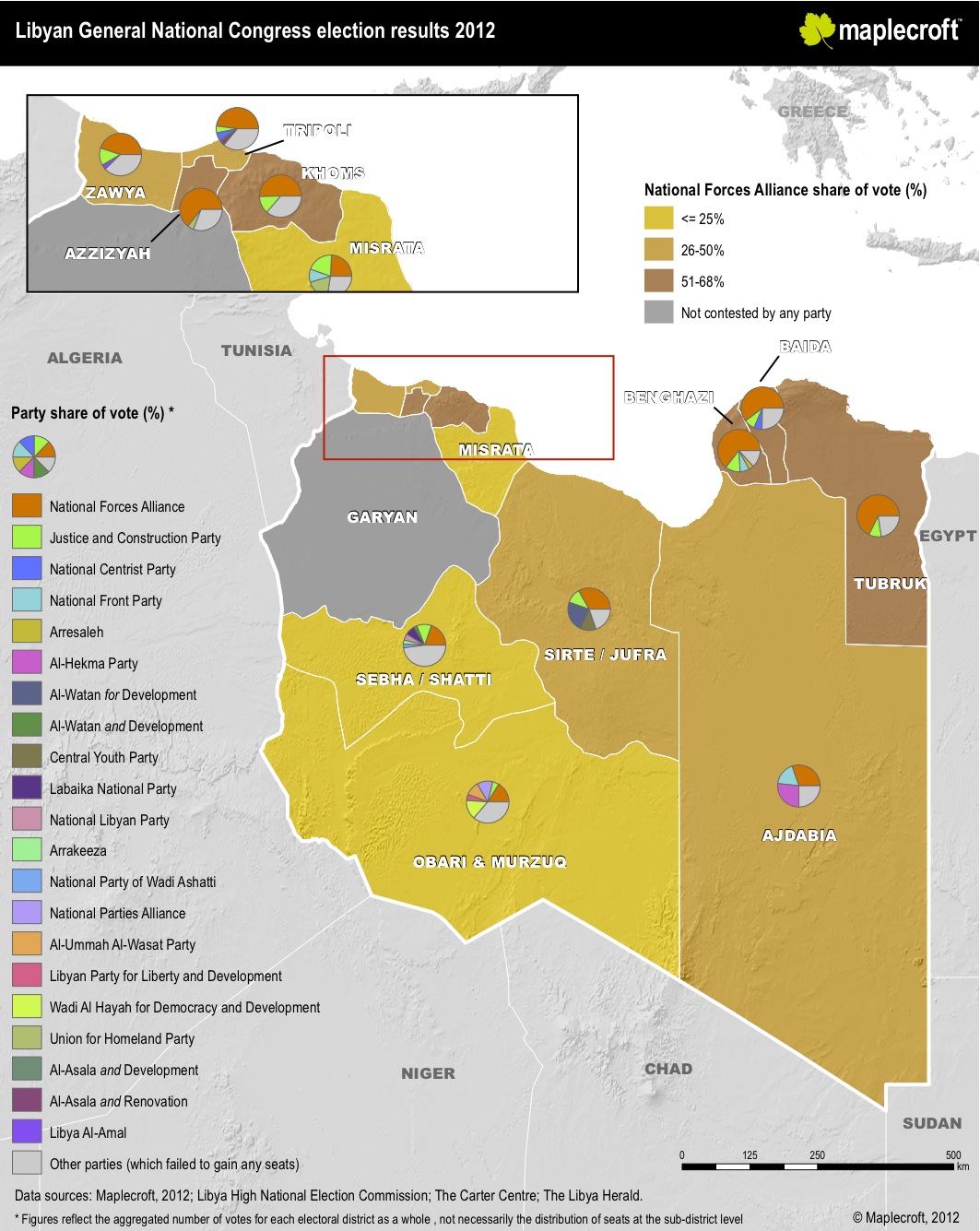

In today’s Libya, local is king. In late February, Misurata, the third largest city, held elections for its city council. This council frequently contests the authority of the NTC inside Misrata. In early March, notables in Benghazi, Libya’s second largest city and capital of the eastern region of Cyrenaica, announced plans to establish an autonomous Cyrenaican government. In mid-May, Benghazi held its own local elections and some strongly anti-NTC candidates did very well.

Repeated armed clashes in cities like Sebha and Kufra have also led to calls for decentralization or special regional autonomy arrangements. These calls for the delegation of overlapping, autonomous, and ill-defined powers to local and regional councils — dubbed “federalism” in Libyan political discourse — bear little resemblance to arrangements found in Switzerland, India, or the United States.

Poorly informed commentators warn that the country is poised to fracture along tribal and regional lines, often suggesting decentralization is the solution to Libya’s problems. They forget that the United Kingdom of Libya emerged at independence in 1951 as a federal state. For the next 12 years, four governments sitting in two national and three provincial capitals ruled Libya. Liaison between them was poor, often resulting in conflicting policies and a duplication of services. With the rapid construction of a modern infrastructure after the discovery of oil in 1959, the deficiencies of a federal system became increasingly obvious. In 1963, the King changed Libya into a unitary state. By that time, the number of government employees had mushroomed to 12 percent of the labor force, the highest then in the world.

In the short term, a decentralized government, with the Oil Ministry in Benghazi, the Culture Ministry in Zintan, and so forth, would be popular with powerful regional constituencies (and their militias). In the long run, it would result in bloated bureaucracies and dysfunctional governance. The related talk of creating 50 local councils and administrative offices, each with its own budget, would add to the confusion and waste.

More dangerous still, is the concept of convening the constitutional convention along the lines of the 1951 precedent. Bewilderingly, this principle was enshrined in a late March amendment to the draft NTC constitution — seemingly as a gesture of appeasement to the Cyrenaican federalists. It entails that the 200 person elected National Assembly select 20 unelected members from each of Tripolitania, Fezzan, and Cyrenaica to draft the constitution. This method would give far more weight to Fezzan and Cyrenaica than is their due demographically and would severely short change Tripolitania. In 1951, this method was imposed by Britain via their accomplice the UN High Commissioner, Adrian Pelt, to secure Western interests in Libya. In 2012, it could serve to tip the scales in favour of counter-productive federalism.

Instead of returning to past practice, Libya should move forward and seize the opportunity to diversify its economy and strengthen its institutions. The Libyan people are intelligent, hard-working, entrepreneurial, and capable of the highest ethical standards. Unfortunately, the Gadhafi regime did not promote and reward these virtues. Advancement in his command economy more often depended on family, clan, and tribal ties or other forms of nepotism and cronyism. The new Libya requires the rapid creation of nation-wide institutions and the development of the human resources necessary to improve productivity, and guarantee competitiveness in the global economy. History suggests these goals are incompatible with excessive decentralization and overlapping jurisdictions.

The proponents of federalism want to decide taxes and budgets at the municipal and provincial levels — a sure recipe for gridlock. One of the few positive legacies of Gadhafi’s rule was his construction of extensive oil and water pipelines that linked the provinces together. The bulk of Libya’s oil is extracted in Cyrenaica and brought via pipelines to the Sirte Basin, and the majority of Libya’s groundwater comes from aquifers in southern Cyrenaica but is consumed in the populous areas of Western Tripolitania. A return to a federal model would endanger these gains, unleashing competition between the provinces over these strategic resources. It would also weaken the central government, making it difficult to improve security and secure the nation’s borders.

The myriad shortcomings of the interim government point to an alternative: the careful delegation of limited powers to the local bodies formed during the uprising, linking them to the central government. Misratans and Benghazians should run municipal affairs through their new democratically-elected local councils – but only as representatives of the central government, not as their own fiefdoms. In post-Gadhafi Libya, local and regional bodies must have a say, but federalism is not the best way to give them that voice.

Jason Pack researches Libyan history at Cambridge University and is President of Libya-Analysis.com.

Ronald Bruce St John is the author of several books on Libya, including Libya: From Colony to Revolution (2012) and Libya: Continuity and Change (2011). [/restrict]