By Libya Herald staff.

Tunis, 12 February 2015:

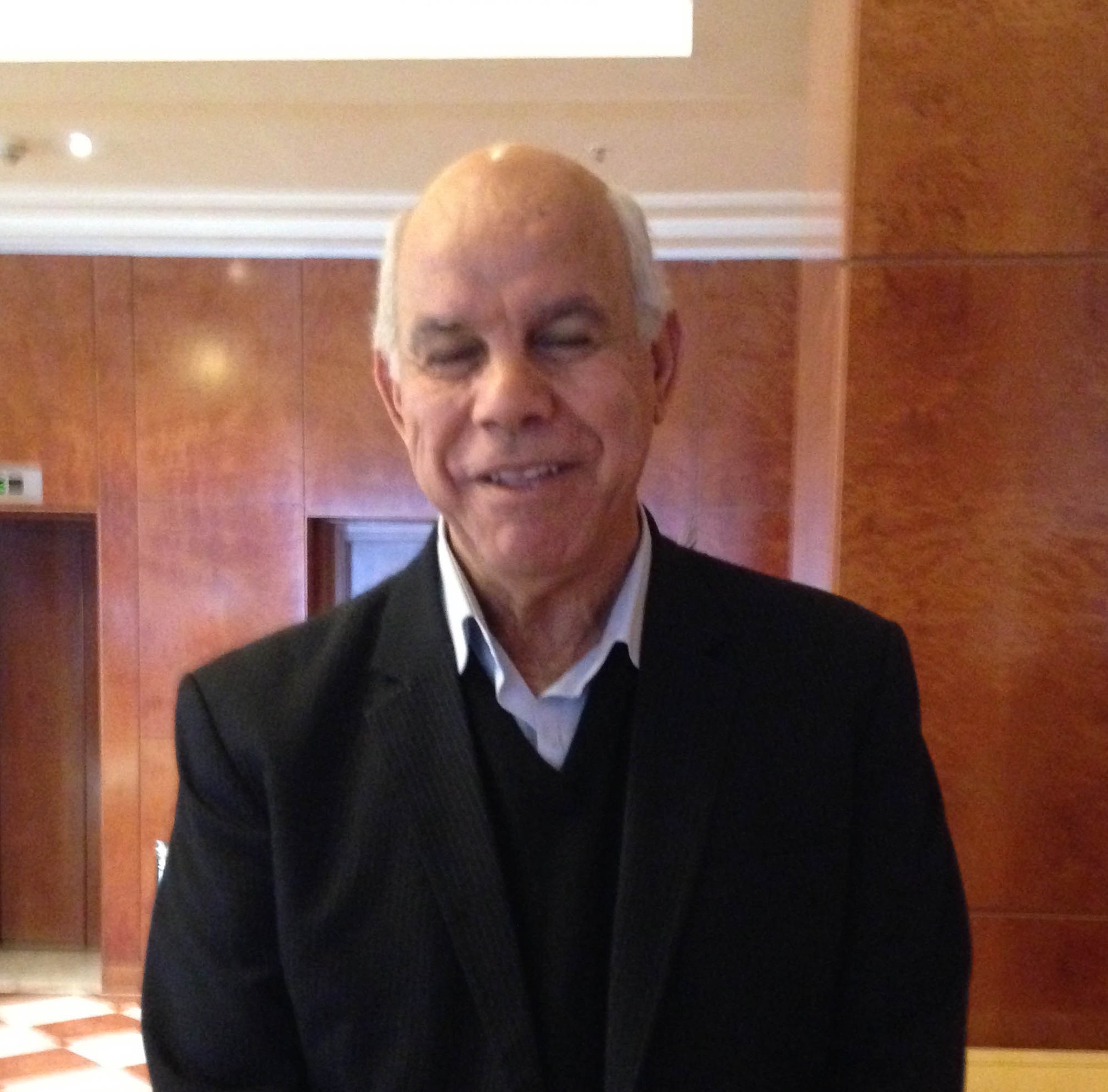

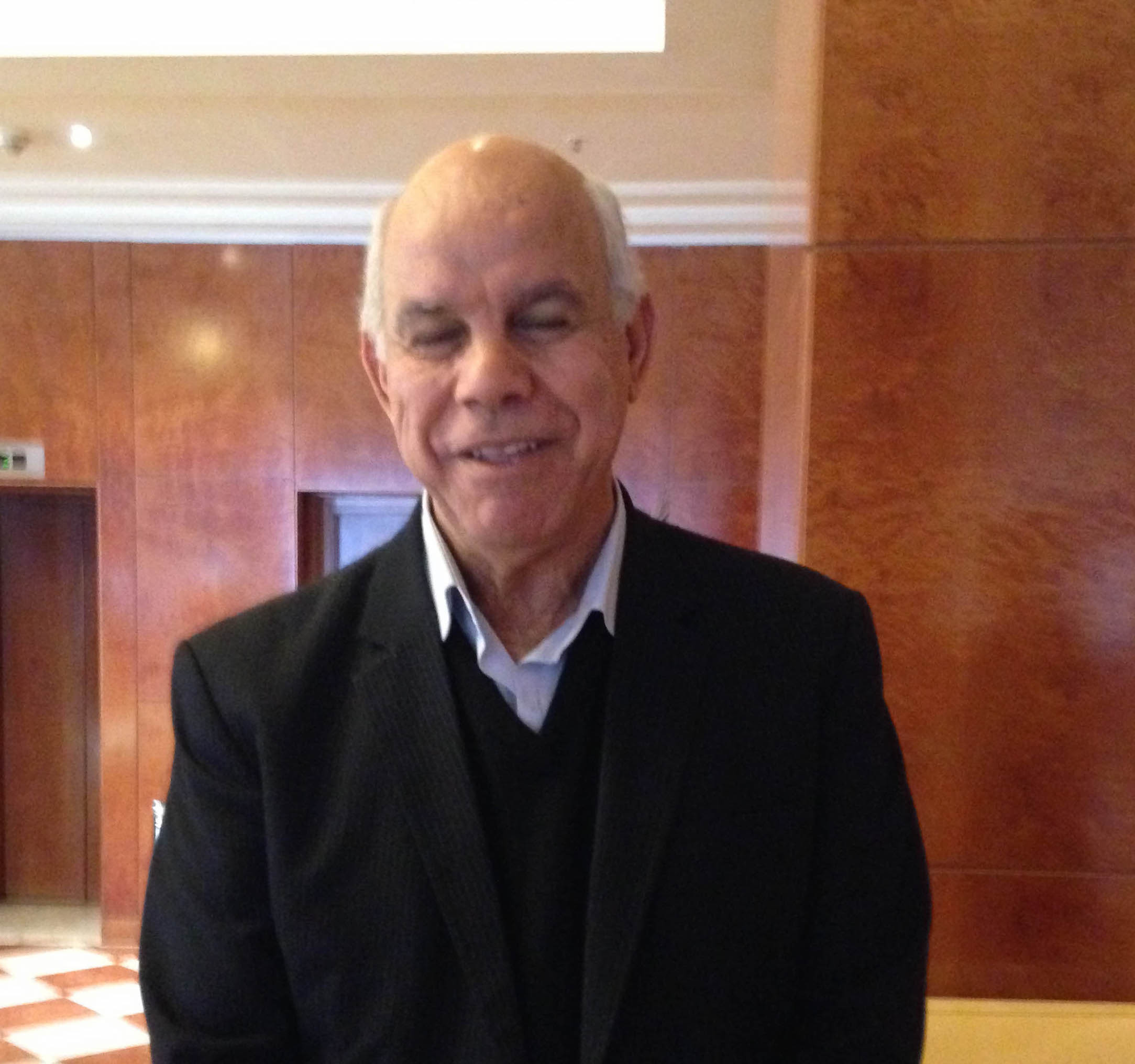

The planned government of . . .[restrict]national unity – one of the major objectives of the current UN-brokered dialogue – must consist of moderates, according to Imhamed Shouaib who leads the House of Representatives’ delegation to talks – and it has to agreed very soon. .

“We’re facing the disintegration of the state. Time is not on our side,” Shouaib said in an interview with the Libya Herald today.

He was nonetheless adamant that there could be no place in the new administration for anyone who has been part of the problems since the revolution. Asked if people such as Omar Al-Hassi, Salah Badi or Abdurrahman Sewehli could have a role, he firmly dismissed them. “There can be no controversial figures”, he said.

The prime minister had to be someone who all Libyans could respect, he insisted. He could be a technocrat, Shouaib added, but he and his government had to be strong.

The big issue, however, was that the new government, once unveiled and agreed, would have to have immediate, active support from the international community. “It will have no leverage to impose its authority,” he warned. “Unless it receives the full support of the international community, it will fail from the start.” He did not go into detail as to what that support might be, although he suggested that there could be financial and other sanctions imposed against those opposed to it.

It was the lack of international support that had brought Libya to its present situation, he said. If the international community had supported the democratically elected HoR after the controversial Supreme Court ruling in November, Libya would not be in the current crisis, he claimed.

The issue now, however, was not about legitimacy. There was a political problem and it had to be resolved and quickly. “We’re facing the disintegration of the state,” Shouaib warned. Terrorism was gaining a foothold in Libya.

Europe in particular had to support democracy in Libya. It was in its own interests to do so. Otherwise there would be terrorists on its doorstep. Having failed to prevent the spread of terrorism in Syria and Iraq, at least in Libya there was the chance now to do so. But until very recently, Europeans and the international community had failed to see the threat of terrorism in Libya.

Part of the problem had been the role in Libya of so-called “moderate” Islamists, he said. They had been put in key positions in the government and state sector after the revolution. But they were not “moderate”. They had opened the doors to hardliners, and Libya was now suffering.

Even so, he remained optimistic about the future despite having had his home in Zawia burned twice by militants. “I have a dream,” he said quoting Marin Luther King – a dream there would be a political solution and Libya would be stable. Yes, he said, the optimism was not the same as four years ago after the revolution. “People are very disappointed at what has happened.” But they still had eager hopes for the future.

Moreover, he pointed out, Libya Dawn and the General National Congress were fracturing. Misrata was tired of the conflict. Suggesting also that the country was not as divided between ideologues and pragmatists as was being portrayed, he noted that Libya Dawn was not a monolithic entity. A large number of those supporting it were doing so because of local loyalties or family bonds or for other reasons. And the young men currently in militias that were part of Libya Dawn or the hard-line Islamists, their real objectives were economic, he said. They want jobs and opportunities, a stake in society.

As for the Muslim Brotherhood, it could have a role to play but it needed a new vision. “They need to look forwards, not backwards. That’s why they failed to win a majority [in the June elections],” he said, expressing the hope that it could be influenced by the Muslim Brotherhood in Tunisia and Morocco, in particular by Rachid Ghannouchi, leader of Tunisia’s Ennahda party – not by the Egyptian MB which was stuck in the past.

In regard to Egypt, Shouaib did not think that its concerns over Libya would see it actively intervening. Its prime interest was that Libya not be a cause of instability in Egypt itself, he said. It was not looking to support any individual such as Khalifa Hafter. “Their current alliances in Libya may change”, he suggested.

Nonetheless, given the present situation and international concern, it was vital that Libya not become a political football, fought over by other powers, its problems internationalised. That would make matters far worse. [/restrict]