By Nuri Twebti.

Tripoli, 21 November 2013:

The dramatic events in Libya over the past . . .[restrict]3 years represent a massive change for all involved. However, while the struggle to topple the Gaddafi regime was traumatic in itself, it signified only the end of one era and the start of another. The few months and years that follow are where the actual change will happen.

Change is a disruptive process of transition for individuals, organisations and society. As with any process, change needs to be managed with active leadership to ensure a successful outcome.

Over the past few decades a field of knowledge has emerged to study change, reduce the negative impact of disruption, and help navigate a way to a better status. This field is known as “Change Management” with roots in Social Science and management techniques[1]. The primary applications of this field have been in the business world, but the principles are applicable to any organisation undergoing change.

This article provides an overview of the field to suggest ideas for the leaders of the new Libya. It is not a substitute for more detailed professional expertise. Such expertise may already be possessed by members or advisors of the Libyan Government. It is also available from a number of public and commercial institutions around the world.

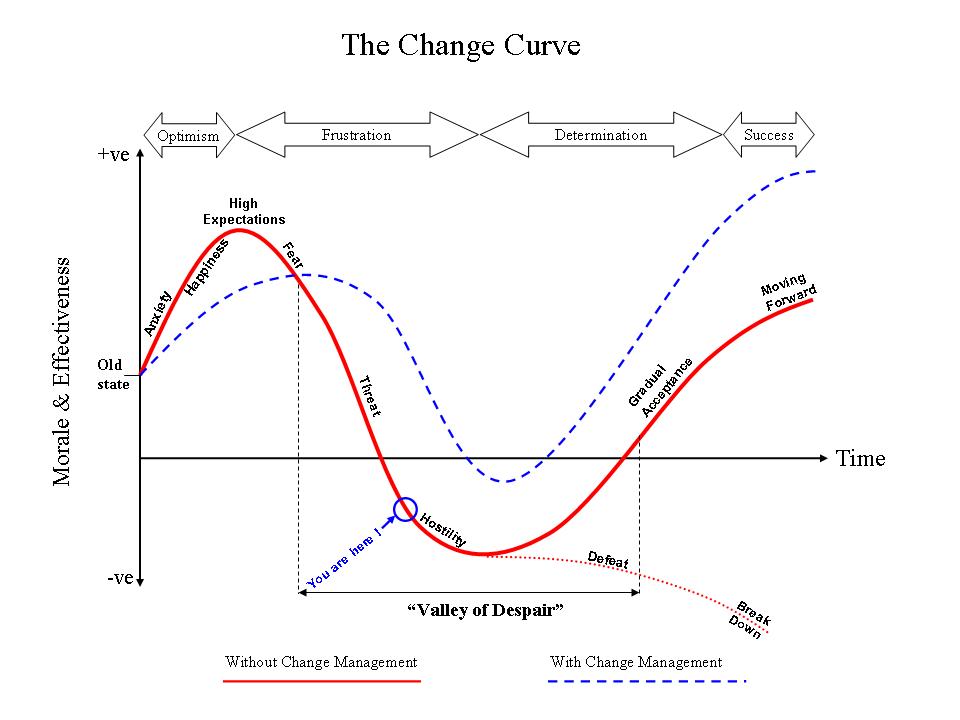

As stated above, change is a process of transition, or a journey. It is typically summarised by the following diagram[2] which illustrates the different phases of change, and the associated behaviours that emerge during each phase.

The fact that most change happens in this way should give hope to people who are in the middle of change. They may feel that they are lost but in reality they are following a natural course.

Experience suggests four predictable phases to the change process: 1-Optimism, 2-Frustration, 3-Determination and 4-Success, with a dangerous period called the “Valley of Despair”.

The simple knowledge of these phases, and what to do about them, is critical for leaders who must manage the change. On the other hand, ignorance of these characteristics leads to chaotic debates, rumours, infighting and failure for all.

Notice, “leadership” is a quality possessed by some individuals who are able to communicate a vision and shape public opinion, while “management” is a process. Therefore, leadership and communication are essential ingredients for change management.

The phases are:

(1) Optimism, and the need to “manage expectations”

At the point of starting change there is a short period of anxiety, which quickly gives way to high levels of optimism and euphoria about the new era and the untold possibilities.

Leaders need to use this short “honeymoon” period to establish trust, and inspire people. Because change causes turbulence to most functions in society, leaders need to have viable stabilisation plans and actions to reduce turbulence. This is also the time to work hard to create, and communicate, a clear vision, with simple plans for the transition.

Leaders also need to step in at this point to manage expectations. They need to be clear about the constraints and challenges ahead and limit demands, or phase them out over a realistic time period. This is the essence of “Program Management” and “Portfolio Management” techniques which handle competing priorities within a constrained system of budgets, resources and risks.

Not managing expectations or being blind to constraints can actually set the scene for the failure of change! Or, at the very least, makes the inevitable phase of “Frustration” and the “Valley of despair” period more prolonged, difficult and dangerous.

Ironically the largest threat at this stage usually comes from the leadership team themselves as they “jockey” for position and influence in the new fluid environment. They may become so preoccupied with theory and ideology and power that their basic duties of stabilisation, planning and teaming do not get enough focus.

Unfortunately, this phase of change was not managed well in Libya. Wild promises were made by many with unrealistically high expectations about what is possible and the speed of implementation. Declarations were made before the mechanisms for managing them were in place, which in turn led to exploitation of the weak systems of governance and finance disbursements. Several officials over-estimated the financial resources of Libya, while under-estimating its current and future commitments. The challenge of rebuilding state institutions, and change attitudes were not seriously addressed. In addition the public infighting within the leadership eroded public trust and squandered local and international goodwill.

(2) Enter Frustration

After the euphoria of early expectations, reality starts to takeover. The challenges and constraints become visible. The breakdown of traditional structures and centres of authority creates an environment of uncertainty and confusion. Since people operate out of their needs (Maslow 1943) and defence mechanisms (Argyris 2004) the new environment and the challenges become a source of fear for most. By the same basic principles, people with vested interests from the old status will fear change and will actively or passively resist it. Hence the need to communicate and reconcile, not antagonise.

At times of uncertainty, especially in the presence of armed groups or violence, people resort to basic affiliations of tribe, ethnic group or town to seek shelter from the threat to their basic needs. This creates “ghetto” mentalities, polarised views and mistrust of others. The ghetto quickly replaces the national interest in the minds of people. Such environment leads to distorted perceptions, false information, and infighting. When left unchecked, these negative behaviours become a self-sustaining downward spiral.

The stages of fear and threat will at some point turn into hostility against change. Groups will start to question the benefits gained from starting the change in the first place. Traditionally, this is the stage where challenge to leadership will arise as people start to look for someone to “rescue” them from chaos and lead them out of the “valley of despair”. This period is fertile ground for dictators and ideologues to grab power.

Assuming that basic stabilisation and planning steps were taken earlier, the best proven way to reduce the negative impact of frustration is through clear honest communication that removes ambiguity about the present, defines the steps for the future and highlight quick wins. Proactive communication is crucial. Change management specialist John P. Kotter maintains “All successful cases of major change seem to include tens of thousands of communications that help people deal with difficult intellectual and emotional issues”. Leaders need to shape public opinion via Proactive Communication.

(3) Determination. The light at the end of the tunnel.

Assuming stabilisation, planning and communication did take place then the results of implementing processes, laws, institutions … etc will start to show “early wins”.

Unfortunately, in the case of Libya, the critical first stage of stabilisation was undermined by competing interests that prevented establishing the force of law, without which the state and leaders can not function. It is not too late to establish stability, but the window of opportunity is closing fast. The state must assert its authority by taking offensive action against selected small groups who threaten pubic safety and stability. Appeasement is always fatal. Deterrence against small selected groups will set an example and make others fall in line with a positive chain reaction.

This will re-establish trust. People will start to see the “light at the end of the tunnel” and will become determined. The impact on morale will be immediate and society will start to climb towards success. Earlier doubts will start to dissipate. As basic needs (Maslow) start to be met, people will emerge into higher levels of cooperation. As the individual and collective interest becomes visible a new sense of optimism will help drive a more sustained recovery. This is similar to the concept of “sentiment” that drives economies and markets forward.

The new trend is usually very delicate and vulnerable to reversals. The implementation of “new ways” needs to accumulate small wins until sufficient momentum is built to overcome fear, threat and hostility. Only then can the momentum of positive sentiment secure more determination to achieve the considerable work that is still ahead.

(4) Climbing into Success

As more solutions and changes are implemented, people are pleased to be involved and to contribute. Success breeds confidence which fuels further success.

It is important not to declare victory too soon, before processes, institutions, controls and laws are in place to maintain the gains. Old habits die hard, while new ones require much repetition before they become standard practice. Therefore compliance and control measures and law should be built-in he fabric of the new government and social institutions.

In summary, Libyan leaders need to be aware of the phases and characteristics of change, resolve their leadership issues to create a performing state, manage expectations, create realistic plans, provide stabilisation measures to compensate for turbulence, and continuously communicate with the population through clear proactive messages that counter ambiguity and address the basic needs and fears of people.

By doing so it is possible to avoid the severe and prolonged impacts of change ( Red line on the curve ) and navigate an easier, shorter more successful change ( Blue dotted line on the curve )

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of Libya Herald.

[1] Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, Elizabeth Kübler-Ross’s five stages of grief, Six Sigma techniques.

[2] John Fisher’s process of transition, John Kotter’s Change Model

[/restrict]