By Mustafa J. Salem, Geology Department, University of Tripoli.

Tripoli, 19 April, 2013:

Libya is a vast country that contains hundreds of major sites, representing . . .[restrict]various periods of history. Its landscape is also variable and this makes it highly attractive to those looking for adventure. Besides its long and mostly unpopulated coastline, it has numerous mountains, wadis, gravel plains, volcanic fields and, of course, great sand seas.

On the coast lie some of the biggest and most famous Graeco-Roman remains in the world, notably those in the Pentapolis (the five cities of Cyrene, Taucheira, Euesperides, Ptolemais and Barce) in the eastern part of Libya and the “Tripolis” (the three cities of Leptis Magna, Oea and Sabratha) in the northwest. Many more monuments and classical archaeological remains lie scattered in wadis and plains both in the northeast and the northwest, for example the numerous remains at Girza and Wadi Suf Ajjin.

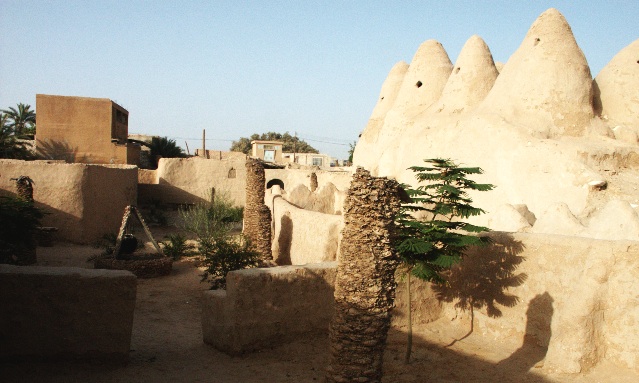

Islamic remains are also found in parts of Libya – in the north and east as well as in the oases of the south. There are numerous scattered remains in Jebel Nafusa, the desert oases such as Ghadames, Ghat, Zuilah, Awjilah and Murzuk plus others around the main cities of Tripoli, Benghazi and Sebha.

Most of these historic sites suffer from a lack of proper maintenance, a lack of reliable security and a lack of appropriate programmes to raise public awareness as to their existence and to emphasize their importance as key parts of Libya’s cultural heritage. Since they are monumental and mostly lie within populated areas, their deterioration is gradual, except where they were demolished through political or administrative decisions as was the case with the historic towns of Soknah, Murzuk and others which were rebuilt as low-income flats and houses.

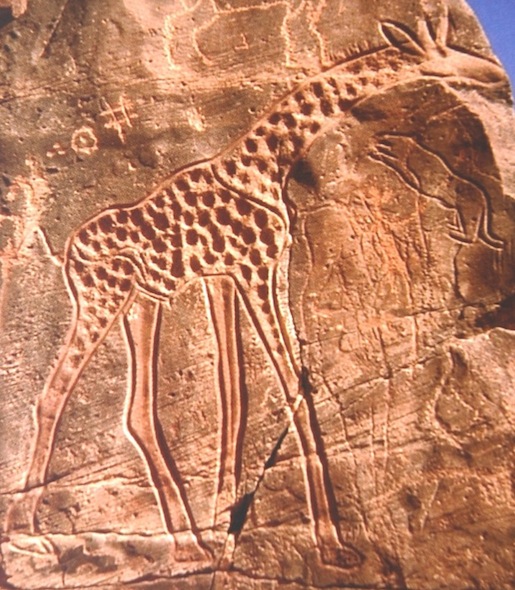

But beyond that, probably the most fragile and vulnerable to damage, theft and natural deterioration are those valuable prehistoric remains in the south, south-east and central Libya, and the terrain on which they are located. These include wadis, escarpments and caves that contain thousands of examples of rock art of various types – paintings such as those in Akakus, Awaynat and Wadi Aramat and engravings like those in Messak Sattefet, Wadi Ash-Shati, Al-Hamadah, Al-Haruj Al-Aswad and several other areas in central and southern Libya. Besides these sites, some of which are recognized by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites, there are thousands of scattered remains all over Libya – prehistoric tools, pottery, fire hearts, trapping stones, burial sites and other artifacts. These archaeological remains are even more vulnerable to damage, displacement and loss by being moved or collected by visitors. In most cases these untended artefacts are protected by either being hidden under the sand or being in inaccessible parts of the desert, in sand dunes, remote wadis and difficult terrain.

In the last two decades however, the Fezzan, where most of these important sites are to be found, has increasingly been visited by tourists interested in seeing these sites or by adventurers who enjoy desert travel. Unfortunately, some of the visitors collect these valuable items and smuggle them through the borders. Oil industry workers are another group who, while mainly looking for oil, sometimes also collect these items as souvenirs. Many more of these archaeological remains are either damaged by, or temporarily hidden under, vehicle tracks.

With the expansion of oil exploration and exploitation in the Fezzan, many new tracks and paths have been opened in the search for oil. These have provided access to the fragile areas that until 20 or so years ago were inaccessible and have therefore enabled far more people to access these previously unreachable wadis and plains.

Unfortunately, these areas of important archaeological sites are also very environmentally fragile. They are located in hyper-arid areas with an almost negligible annual rainfall (10-20mm). These areas contain wadis with rare flora, endangered fauna and a very fragile terrain. The sudden increase of vehicles, machinery and humans has not only reduced the number of rare fauna and destroyed the flora but also damaged the desert surface through unconstrained driving creating numerous tracks. Abandoned oil well sites and base camps with surfaces damaged by myriad tracks and scattered solid and liquid remains have all had a negative impact on the Libyan desert and its fragile ecosystem.

Role of the Scientific Community

Archaeologists and anthropologists are doing their best to record these remains and report their scientific value while they are still in situ, because if they are removed from their position they lose their scientific value. Scientists, though, are falling behind in documenting sites with more accessible routes because they cannot keep up with the sudden increase in the number of visitors to these areas and the damage they cause to the natural and human heritage, whether intentionally or accidentally.

Since the beginning of the revolution two years ago, scientists have been unable to resume their field work due to the security situation, though they are anxious to do so. Under these circumstances they can only try to highlight the problem and hope that until they are able t to go back to the field, no further damage is caused in their absence. Their experience and expertise should be used in national protection programmes for these endangered areas, as they are experts not only in the heritage of these areas but are also very interested in the proper protection of both the heritage of the Libyan Sahara and its artifacts.

The role of industry, especially oil and gas

Industry needs to become more sensitive to the issue of environmental and heritage protection and preservation. There is now legislation to limit the impact of oil-related activities on the environment, landscape and archaeology in the areas in which the oil companies operate. But there is much more to be done in following up current and future operations, such as setting stricter rules and also in mitigating and rectifying past problems and damage caused by operators. Local sustainable development programmes should be instituted where heritage sites are located with the aim of contributing to the protection and preservation of these fragile areas and enabling further research and studies of the Libyan environment and heritage in the Sahara. Such measures will improve conditions and prevent further deterioration, and this should lead to integration of the industry with the local community and environment.

Role of government organisations and agencies

Official government organisations such as the Ministry of Tourism, the Department of Antiquities, the General Environmental Authority and the Ministry of the Interior also have a major role to play. While the Ministry of Tourism’s job is to encourage tourists to visit Libya and to promote Libya as a destination, its duty is also to ensure that the tourist attractions, whether archaeological or natural, should not be impacted or damaged by the visitors. This can be achieved by cooperation with other organisations such as the Department of Antiquities and the General Environmental Authority, and by having strong legislation and the power to enforce it. In order to make the environment and its protection a priority there should be an emphasis on eco-tourism and effective guidelines should be drafted by the Ministry. Desert tourism operators should be licensed and required to comply with those guidelines. Finally, the Ministry of Tourism should provide sound education for key people involved in adventure and cultural and archaeological tourism, especially tour operators and guides.

The Department of Antiquities and the General Environmental Authority should collaborate to improve current legislation and be given the means to enforce it in order to save heritage sites from damage, theft and misuse, and to raise public awareness.

Having said that, they should begin a national program to protect and manage the areas of Akakus, Messak Sattafet and Idhan Murzuk as their first priority, followed by Al-Awaynat-Arknu, Wadi Aramat, Meghidet, Waw An-Namus and the main lakes in Idhan Obari. These areas should be protected by law and be managed as ‘Protected National Parks’ with strictly controlled movements of visitors. Abuse and theft of artifacts should be widely stigmatised.

Official security authorities, tourist police and border immigration authorities should also be involved in helping to prevent the collection or smuggling of any archaeological or heritage items across Libya’s international borders.

Above all, the Libyan government should place a high priority on the issue of natural and human heritage and allocate sufficient resources to implement the conservation and preservation plans that are required. These must include proper training for the human resources needed to accomplish them.

Role of NGOs and Civil Society

Once there is wide public awareness about the crucial issue of the desert environment and its human and natural heritage, the public and civil societies in the areas concerned will react positively, provided that the official authorities and organisations foster and support the initiatives. Some successful examples are already on the ground. Historic towns like Ghadames, Darj, Awjilah and Al-Fugaha were all maintained by direct participation from the local communities of these towns with help from the official authorities. More could be done by civil society if it was encouraged and properly trained.

Major treasures of Libyan and world significance are at imminent risk and urgent action is required to safeguard them for posterity.

[/restrict]