By Amena Raghei.

During the Qaddafi regime, women’s participation in Libyan public life was perceived as little more than a tool in . . .[restrict]Qaddafi’s arsenal of oppression. Recent interviews with female activists and candidates repeatedly echo the sentiment that, unlike today, women who took on public roles during Qaddafi’s time were considered women of ill repute, literally tarnished by Qaddafi’s hands.

While this attitude has been entrenched in the Libyan cultural mindset, it is currently undergoing seismic shifts. As a result of the 17 February Revolution, women have started participating in public life at unprecedented levels. For some members of Libyan society, these changes have been difficult to accept. Nevertheless, Libya’s newly empowered women seem undeterred and determined to protect their new few found public roles.

What it once meant in Libya to be a woman in public

In Libyan society, it was once implicitly understood that women holding positions in the Qaddafi government or pubic positions in general had been chosen not for their ostensible bureaucratic qualifications but, more often than not, as an expression of the “brother leader’s” personal interests, tastes and worse. Libya’s traditionally patriarchal society did not easily allow women to be objects of public scrutiny, especially as decreed by the arbitrary rules of a silently hated dictator.

Qaddafi’s infamous female bodyguards, Benghazi’s female mayor, Huda Ben Amir (better known as Huda the Executioner), and the ubiquitous Revolutionary Committees (which were known to recruit young women and girls to satisfy Qaddafi’s perverse predilections) are a few of examples of female public positions abhorred by the average Libyan.

In order to avoid these negative associations and protect themselves, women often willingly took a backseat to men and refrained from participating in political – or any other public – activities. While this may have preserved women’s reputation, it also created a culture where women’s social roles tended to be restricted mainly to the household. In cases where women ventured outside the home, they were often limited to traditionally acceptable posts with little public exposure or decision-making ability. Their involvement in society remained socially acceptable as long as they stayed away from the limelight and did not seek public attention.

The revolution of 17 February would see a quick and decisive change in this attitude as women, out of necessity, became active, productive and respected members of a national movement. No longer would their political activity carry Qaddafi’s imprimatur.

Elections, democracy and what it means to be a woman in public life in today’s Libya

This summer marked a turning point in Libya’s swift evolution from dictatorship to democracy. It was doubly special for Libyan women, who made their voices heard and took their role in building the new Libya very seriously. Women’s new political roles extended from and even surpassed the contributions made during the revolution. They not only helped in their country’s rebirth, but also took on a new identity as collaborative members in Libya’s public sphere.

On Election Day, 7 July, over 600 Libyan women, from all over Libya and representing all sectors of society, presented themselves as candidates for the General National Congress (GNC). Alongside their male counterparts, these women campaigned as individuals and party members, displaying a hunger for democracy and public representation hardly imaginable to any Libyan – male or female – just one year earlier.

Women candidates uploaded their CVs to the candidate site and readily presented their backgrounds, credentials, pictures and political agendas to their constituents. They gave interviews to local and foreign media. They campaigned with posters, pamphlets and radio ads. They met with and rallied voters on the streets and in town halls. They joined women’s groups, held campaign awareness events and encouraged Libyan women and men to get out and vote.

In the end, thirty-three women were voted into the two hundred-member GNC. While this number represents less than one quarter of the Libyan congress, when viewed within the context of Libyan culture and the de-facto taboo against female political participation, it is an impressive achievement. Most notably, in their first run for public office in Libya’s nascent democracy, women achieved what it took the United States over two centuries to accomplish – 16 percent congressional representation.

Backlash and Cultural Insecurities

Now that Libya appears to be well on the path toward democracy, general comfort levels with women’s public participation have begun to decline.

For some members of Libyan society, it is a cultural struggle to balance Libyan women’s new identity with their traditional roles. For these individuals, the perceived “need” for women’s public participation was not expected to extend beyond the revolution or to become as serious as it has.

The clearest example of these emerging sentiments came on 8 August when power was transferred from the outgoing National Transitional Council (NTC) – the governing body that guided Libya through its revolution and governed the country through the election – to the incoming GNC.

Minutes into the ceremony, the female presenter, Sarah El-Mesallati, was heckled by a male GNC member who told her to “cover (her) head.” When she ignored the heckler, the outgoing chairman of the NTC, Mustafa Abdel Jalil, asked El-Mesallati to leave the podium. She obliged out of respect for the chairman and was replaced by a male presenter who took over for the remainder of the ceremony.

In a population now accustomed to voicing its thoughts and opinions without hesitation, this incident immediately sparked a national debate on women’s personal freedoms in Libya. Overnight, the Facebook page We are all Sara El-Mesellati was created, garnering 1,500 “likes” by 10 a.m. the next morning.

Debates took place between men and women in social media spaces, as well as on the floor of the GNC. As evident in a video, made by the Libyan freelance journalist Huda Abu Zaid, congress member Salah El-Din Badi expressed his distaste for El-Mesallati and accused her of having a hidden agenda. Others interviewed on the video accused the congressman himself of infringing on El-Mesallati’s personal freedoms.

The El-Mesellati incident is only the tip of the iceberg. It pales in comparison with other life-threatening instances of open attacks against women’s civil liberties this summer, including increasingly common stories of harassment and abduction of Libyan women, as noted in a recent article by the well known Libyan activist Niz Ben-Essa.

In August, the Libyan activist, Majduleen Abeida was kidnapped at gunpoint by a group of men while conducting a workshop in Benghazi. There was no apparent reason for her abduction other than her vocal human rights’ activism and perceived tolerance of other religions. Although she was released a few days later, the incident sparked public outrage and led to the creation of the Facebook page We are all Majduleen.

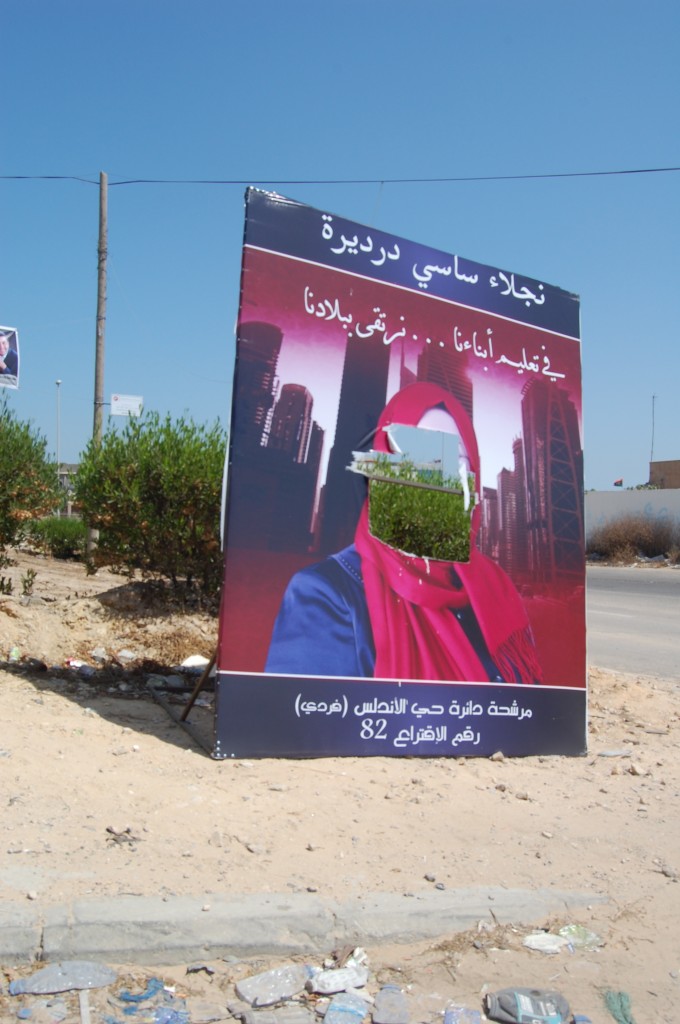

Gradually, a picture is emerging of a Libya where women’s safety is at risk and their security compromised largely because of their public exposure and political activities. This is not to say that all was well before the legislative elections. As Libya drew nearer to elections and the number of campaign posters increased in the streets, so too did the defacement of posters with female images. In some cases, women’s images were entirely blacked out or cut out of posters while the images of male candidates, side by side on the same posters, were left untouched.

Despite these clear statements against women’s public participation, many female candidates remained undeterred and replaced their vandalised posters with new ones. As one female candidate made clear in Benghazi, “these acts upset me and just made me print more posters.” On the other hand, one female candidate in the more conservative city of Misrata said that, in order to avoid harassment, she had opted not to display her image on campaign posters.

Increasingly severe attacks on women’s personal freedoms and security have inspired many Libyan women to stand together and speak out. Exercising their new freedom of speech, scores of Libyan women (and men) have responded loudly and clearly, using social media outlets as well as their positions in newly formed human rights and advocacy organizations to speak out against these assaults.

In direct response to the apparent tolerance toward these acts, a group of activist organizations and advocacy groups within Libyan civil society formed the Coalition of Libyan Women’s Rights to tackle the issue of women’s civil liberties and security through a series of campaigns and protests.

It is worth noting that while these attacks were committed primarily by men, the groups that have emerged to protect women are not solely women’s rights groups nor comprised only of women. They range in interests and membership, from The Free Generation Movement to Lawyers for Justice in Libya, to name just two.

Conclusion: sustaining a new mindset

While women have demonstrated their political savvy in Libya, have broken with many cultural taboos and have risen above the stigma attached to public life, not all sectors of society appear ready to accept their new position in the country.

The events that have occurred over the past few summer months highlight the complex and serious struggle between two mentalities. One, a deeply engrained vestige from an era that has not quite made a complete exit from the Libyan cultural psyche and the other, represented by moderately open-minded, avant-garde thinkers who believe in the equal participation of women in Libyan society.

Without question, women’s increasing role in public life is a new concept for Libyans. While it will take some getting used to, it is happening and cannot be stopped. The 17 February Revolution catalysed changes in popular attitudes toward women and brought about an abrupt shift in both male and female conceptions about the need for women’s participation in public and private life.

For Libya, the challenge ahead is to entrench public attitudes that respect personal freedoms and to accept women as a normal part of the public sphere. The real trick will be to sustain this mindset beyond the revolution and current transition.

Amena Raghei is an independent researcher and MA in International Affairs candidate at The New School, New York, USA, where her concentration is in Governance and Human Rights with a focus on Middle East and North Africa.

This article was first published in Muftah.org and has been reproduced with the magazine’s permission. [/restrict]