By Mustafa J. Salem.

February 2014:

Ahmed Mohammed Hassanein Bey was an Egyptian graduate of Oxford . . .[restrict]University, a diplomat, Olympic athlete, writer, photographer, explorer and tutor to King Farouk. He published in the National Geographic Journal, September 1924, a long article describing his 2,200-mile Libyan desert trip which he completed in 1923 and in which he crossed the eastern side of Libya and continued his down to northern Sudan. His camel expedition, which lasted for more than six months, was intended to find a link between Kufra in southern Libya and Al-Fasher in northern Sudan.

He explained his objectives: “After my desert journey to the oasis of Kufra in 1921, my sovereign manifested special interest in a proposed undertaking to bridge the gap between Kufra and El Fasher.”

According to Hassanein Bey, the trip resulted in two important interesting results. The first and most important was the fact that he reported the presence of a good source of water in Jebel Awaynat which has since enabled travelers from Kufra to cross to Sudan stopping at Awaynat for water supplies. His second important reported discovery was the presence of several sites in Awaynat with pre-historic engravings and paintings which have since been studied and which indicated that the history of these areas extends back thousands of years.

Hassanein Bey laid the ground for spreading the importance of Jebel Arknu and Awaynat in his article in National Geographic Magazine and in his book, The Lost Oases, which was published a year later.

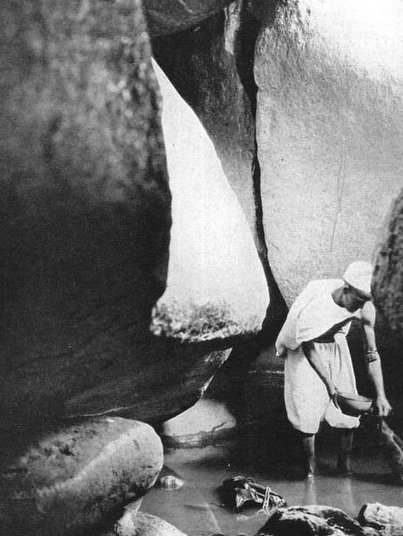

In his description of the discovery of water in the Awaynat mountain, he says: “We found ample supplies of water in the deep-shaded recesses of the cliffs…. they are not depressions in the desert with underground reservoirs but mountain areas, where rain water collects in natural basins in the rocks. There are said to be seven such basins at Awaynat. I visited four and found that the water of good quality” (Figures 2 and 3).

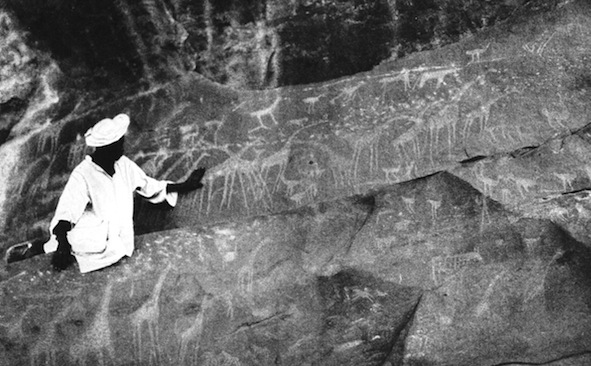

Hassanein’s other important discovery in his historic trip was described as follows: “It was in Awaynat that I made the most interesting find of my 2,200-mile journey. I had heard rumours of the existence of certain pictographs on rocks…., I was led by a native to the picture rocks. The animals are rudely drawn, but not unskilfully carved. There are lions, giraffes, ostriches, and all kinds of gazelles, but no camels. The carvings are from a half to a quarter of an inch deep and the edges of the lines in some instances are considerably weathered. Perhaps even more significant is the absence of camels from the drawings. If they had been native to the region at time that the carvings were made, surely this most important beast of the desert would have been pictured. But the camel came to Africa from Asia not later 500 BC.” (Figure 8).

From these descriptions Hassanein had not apparently come across any of the colour paintings that are scattered in small shelters and on ledge sides in various areas of east and west Awaynat.

Hassanien’s expedition not only accomplished the objectives laid by him prior to departure, but also enhanced the significance of Kufra as the main oasis in south east Libya, linking Libya with Sudan.

The town, an oasis based on enormous underground water reservoirs, has since gained importance as a desert supply centre for the south of Libya and northern Sudan. Currently there is a heavily used track linking the Kufra with Al-Fasher in Sudan. Besides its huge agricultural project producing various types of produce including mangos, a large amount of this underground water (fossil reservoir) is pumped through the Man-Made River to the coastal towns in the north (Figure 4).

The presence of water in Awaynat and Arknu (the “Lost Oases”), was sufficiently well known that many people from Kufra were able to take refuge in the Al- Awaynat mountain when the Italian General Rodolfo Graziani captured Kufra in 1931. Supported and supplied from Kufra, Awaynat mountain was thereafter a strategic border area that the Italians used as one of their important frontline base in their efforts prior to Second World War to protect the area, and south-eastern Libya in general, from being invaded either by the British from Egypt and Sudan or the French from Chad.

It did not work. The Free French forces under the celebrated General Philippe Leclerc captured it in 1941.

Following the historic visit and detailed description by Hassenein Bey and the discovery of water there, the Awaynat area was visited by a number explorers who were either collecting information about the area for strategic purposes or were looking for legendary town and oasis of Zerzura (“Oasis of the Little Birds”). Perhaps the most frequent visitor in the 1930s prior to World War Two was Count Lazlo Almasy and his colleagues from the so-called Zerzura Club (for details about visits to Awaynat, see The Hunt for Zerzura by Saul Kelly, 2002 published by John Murray).

Landscape and History of Al Awaynat Mountain Area

The Awaynat and Arknu Mountains, situated in the border region between Libya, Sudan and Egypt, with magnificent views, are cut by a number of large valleys which were densely populated in prehistoric times. The area includes hundreds of pre-historic engravings and paintings, which add to its importance as a tourist attraction. These pre-historic sites are found in shelters along the sides of all the main valleys

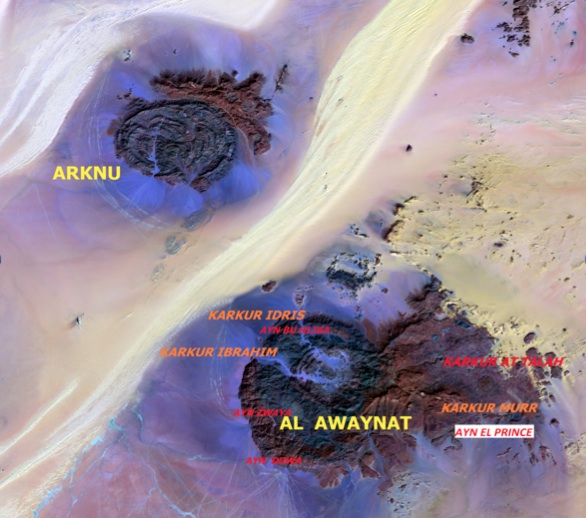

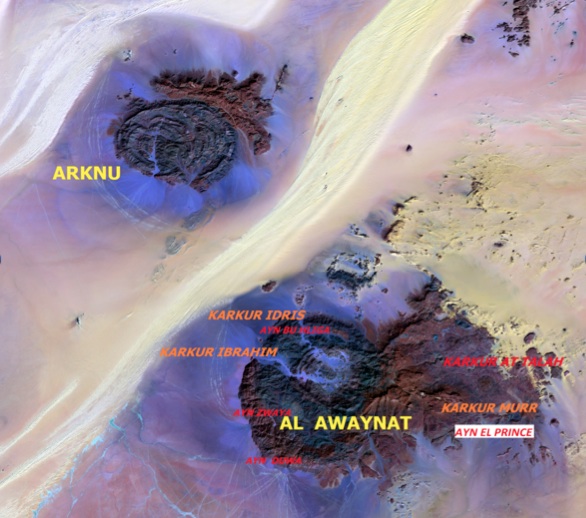

Geologically, the Awaynat Mountain is composed of two very different types of rocks. The western part, lying entirely in Libya, is composed of an of intrusive granitic ring complex, about 25 kilometres in diameter. The interior of the complex is being eroded and is cut by main wadis, with scarce vegetation (Figure 5). These wadis are Karkur Hamid, Karkur Idriss and Karkur Ibrahim draining the interior towards the west. Some permanent springs are found in the western side of the mountain, namely Ayn Zuwaya, Ayn Doua and Ayn Bu Hliga.

The eastern part, which lies in Egyptian territory, consists of a large block of Paleozoic sandstone, resting upon metamorphosed Precambrian Basement rocks. The area is drained by a system of wadis, which merge to form the main Karkur At-Talah which drains toward the east-northeast. A smaller valley, Karkur Murr drains the eastern foothills to the south into the Sudanese territory. Near the mouth of Karkur Murr there is a spring that is called Ayn el Prince (Ayn Murr) (Figure 1).

A scientific expedition to the Arknu and Al Awaynat mountains, organised by the Antiquity Department with the University La Sapienza (Rome), shed light several years ago on an unexpectedly rich cultural heritage, testifying human occupation from the Old Stone Age to late Holocene. Several sites of various archaeological periods were recognised by the mission. Sites belonging to the Pastoral Neolithic with desert artwork were identified. Sites with lithics, ceramics, fireplaces and grinding stones and tethering stones were also reported by the experts of the expedition.

But probably the most informative “recent” online site about the Eastern Libyan Desert can be found at The Libyan Desert FJ Expeditions. This important site was initiated and developed by Andras Zboray and Magdi Zboray, who have been visiting the areas of Awaynat and Gilf El-Kebir in Libya and Egypt for more than 20 years. They have undertaken over 20 expeditions to the areas. From the listing reported by Zboray in 2003 (Sahara Journal, 14, 2003, pp 111-127), it is evident that eastern Awaynat (Karkur At-Talah and its tributaries) contains far more prehistoric art sites than previously reported (various parts of Karkur At-Talah, 234 sites; various parts of western Awaynat, 29 sites; Karkur Murr, four sites and Jebel Arknu, eight sites).

The prehistoric artwork of the western part of Awaynat was studied by various workers over the years. According to Andras Zboray, Almasy and Count Lodovico di Caporiacco were the first to discover paintings in Ayn Dua (western Al Awaynat) in 1933.

In the area of Bu Hliga which lies between Karkur Hamid and Karkur Idris, four sites were reported by different explorers. Jean-Loïc Le Quellec published an important work on these sites in 1998. He indicated that these paintings do not exceed 2000 BC. Le Quellec, also during his visit to Al-Awaynat found four new sites in Karkur Ibrahim, including an interesting shelter with a well preserved large group of cattle and humans (Figure 7) .

The eastern part of Al-Awaynat is as interesting as the western part due to its rock formation and historic content. The area is cut by a major valley system (Karkur At-Talah) which drains toward the north east. This valley is dense with vegetation cover, besides its richness in engravings and paintings. According to Zboray, the central part of the wadi is rich in old engravings, which include giraffes and ostriches, but no elephants or rhinoceros (Figure 8).

While the engravings, which are older, have variations in types of faunas, the paintings in this Karkur At-Talah wadi are mostly formed of cattle. This puts these paintings within the ‘bovid stage’.

- Figure 8: One of the sites that were reported by Hassanein Bey (1924), with engravings of wild animals, including, giraffes, ostriches and gazelles. According to the archaeologists, who worked in the area, these engravings are older than the paintings, which are more common in the Al-Awaynat area. (Photo: from Saharasafaris.org)

Developing Al-Awaynat area as a destination

Al-Awaynat forms an important geological complex which is worth visiting, by experts as well as by adventurers.

Its diversified landscape, variety of rock types (igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic), its content of rare fauna and flora and its unique heritage content (prehistoric engravings and paintings) makes this area very attractive as a tourist destination, provided it is developed, well managed and promoted (Figures 6 and 7).

The fact that the complex is located in a border area between three neighbouring countries (Libya, Egypt and Sudan) requires proper collaboration between them so that it will be established as a ‘Geopark’. This is achievable.

Though quite remote, the area could be developed for small groups of interested tourists and scientists starting either from Libya or Egypt.

From the Libyan side Kufra airport could be used to reach it. En route to Al-Awaynat some interesting landscape could be visited – Jebel Azba and Aknu (Figures 5a and 9), as well as some of Second World War sites. An ideal arrangement would be to be able to visit the east and west parts of Al-Awaynat if some practical arrangements could be coordinated between the border authorities in Libya and Egypt.

In such a case, visitors from Egypt could also combine the visit to Gilf el Kabir with Al Awaynat (west and east).

But till that happens, the area of Al-Awaynat remains an important border crossing point between Libya and northern Sudan, with heavy traffic – some of which involves not only regular border traffic but also smuggling activities.