By Alessandra Bocchi.

Tunis, 12 March 2017:

Libya has seen a blossoming of artists since the revolution, especially female artists.

“My goal is to make people get lost inside of my paintings” said Faiza Ramadan, a young artist from Tripoli – the city that finds itself at the centre of the second Libyan civil war. Her art is made of rough lines making imperfect forms, intended to make people think deeper than what they see on the surface, and explore aspects of psychology that are taboo in her society.

Faiza is one of many young female artists in Libya who have grown since the 2011 revolution. Their work was exhibited in the two-day cultural event من أجل ليبيا (“Min Ajl Libya” – For Libya), at the French Institute in Tunis.

“Of course, it’s not an ideal situation now in Libya”, said art expert Alia Al-Senussi, a member of Libya’s former ruling royal family who works with Art Basel as well as chairing the Young Tate Patrons. “But at the same time there is this rupture, and in a rupture you always have a possibility to bring forth light, and I think Libya is at this point right now,” she added.

It was she who suggested some of the many artists showing at the Tunis event.

Nineteen-year-old Takawa Barnousa is making a career out of her art of using Arabic calligraphy in a contemporary style. Despite being too young to take part in the revolution of 2011, she says she recognises how it provided her with the opportunity to express herself. But in doing so, the revolution also marked a new division between the young and the old.

Barnousa says she has difficulties in finding guidance from the older Libyan artists because of a “gap in communication and collaboration between the old and the new generations”. The contemporary art of the young, she feels, is not appreciated by many of those who were part of the surrealist movement of the 1960s and 1970s. For example, a drawing of the Statue of Liberty in Libyan traditional clothing, by artist Alla R. Budabbus, was meant to symbolise Libyan freedom, but according to Tawka, it was not considered real art by many older artists.

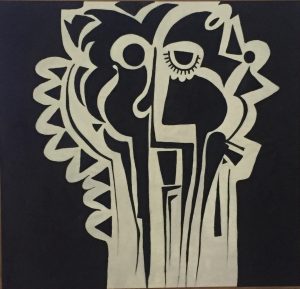

“I don’t think the former regime was holding this new art back,” said 23-year-old Malak Elabbar, who makes her art while also studying architecture in Benghazi. Malak says the revolution acted as a release – a “shift from an old reality to a new one.” She has a distinct style, by using bold and defined shapes to paint her subjects.

Despite new freedoms brought by the dismantling of a dictatorship, these artists are now concerned by a lack of economic opportunities. Faiza, after having lost her job during the revolution, is working as a teacher for what she says is the main obstacle to her work – “time”.

“I can’t be an artist now without a job, so I work as a teacher to afford to be an artist.”

Barnousa, while having managed to sell her calligraphy work in some furniture shops, is also concerned by the state of the economy.

For her part Malka complains that “the tools are expensive”.

Established artist Hadia Gana, who is celebrated for her conceptual work, said it is a lack of galleries and public spaces to showcase art that is the real problem. Gana is well-known among Libyan artists for exploring abstract concepts through a mixture of words, images and video clips. Her installation at the show starts with a vodeo clip from a BBC interview with Qaddafi in 1977 where he says “they hate us”, followed by grained images of tortured subjects, set against calligraphics from the revolution on the floor, surrounded by scattered objects of tins and bags. The objects are meant to portray different communities’ spaces, where each looks after their own. She says Qaddafi’s claim that “they hate us” has penetrated Libyan life to this day, where there is mistrust and thereby egotism, both among individuals and groups in society.

These young artists are looking for opportunities to share their work internationally, to change the perception of who they are. “I want the rest of the world to know that we are normal people. We work. We study. We have hobbies and we have ambitions. We are not terrorists,” said Faiza.

They have different messages, techniques and styles. And despite the divisions in Libyan society, they have created an online community of artists where they share their work.

“Technology and social media played a big role in making the change happen, and in allowing young artists to grow,” Malak explained, adding she always checks enthusiastically on her peers’ work from across the country.

“There is promise. So many of these young and career artists are interested in reaching out to the rest of the world”, said Alia Al-Senussi. In the meantime, their art continues to grow in the midst of the country’s civil war.

Supported by the French embassies to both Libya and Tunisia, من أجل ليبيا ended today.