By Dr Claudio Bencini.

Fauglia, Italy, 23 September 2013:

A number of Berber heritage sites in Tripolitania has been singled out by Italian . . .[restrict]NGO the Wadi Adrar Foundation as being of exceptional archaeological and cultural value. Dr Claudio Bencini, head of the Wadi Adrar Foundation, explains the importance of these sites.

The cultural landscapes in Jefara, Adrar Nafusa and Hamada Al Hamra contain historic Berber sites where the nomadic peoples settled before Roman civilisation. They cultivated specific habitats symbiotic with their surrounding natural desert and mountain environments.

The Wadi Adrar Foundation has identified seven important types of archaeological remains during eight covert survey missions between 2003 and 2010. One survey mission, the first undertaken with the permission of Libya’s Department of Antiquities, has taken place since the revolution.

Berber villages, called tmora, are no longer inhabited but provide unchanged archaeological evidence of the past, despite their state of conservation being relatively poor. Abandoned villages, hamlets and archaeological sites are scattered mostly on the Adrar edge in locations that could be defended.

The Berber villages are formed of dense groups of cave dwellings intermingled with crude stone and gypsum mortar structures. These are either dome-roofed or covered by olive and palm tree trunks intertwined with palm tree leafs, which are coated with an impermeable layer of sand called zimza.

Although habitation of this landscape came to an end at an unknown point in the past, seemingly abruptly, its significant distinguishing features are still visible in these remains.

The Berber landscape is marked by terraces, called tuggherdeit, that are marked out by rude stone walls called tumsa. These were designed for traditional dry olive tree cultivation and these traditional techniques are still used. The Berber landscape is an organically-evolved one which retains an active social role in contemporary society. It is closely associated with traditional ways of living, but the evolutionary process is still in progress.

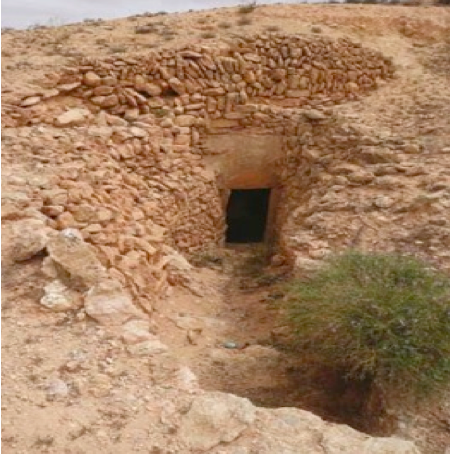

Several villages include a fortified granary – aghrem – in which foodstuffs were collected and stored, and then administered by a guardian called dellal. Here, preserved grains, olives and olive oil were stored in jars and secured in single small rooms, called ghorpha. Each aghrem was protected by a large, lockable wooden door. The archaic model and construction method might reflect a more ancient origin than the other artefacts of the Maghreb.

Troglodyte dwellings, or dammous, have been widely used since ancient times and are still used by some Berber populations, representing a typical and consolidated settlement pattern. Cave dwelling settlements were commonly used for housing, shelters for animals, and even as mosques.

Typical Berber cave dwellings were named abitazioni trogloditiche by the occupying Italian army, following the common thought at the time that troglodyte meant “primitive.” Local peoples were considered to be primitive and uncivilized and a census of cave dwellings was performed to support military security.

These dwellings are found throughout the Jabal Gharbi area, being more concentrated on the western side and progressively decreasing eastward. It appears that, in general, workers chose to excavate dwellings in slopes where rocky strata alternated with softer soil, so that the rocks form the ceiling of the cave. Excavations into soft rocks are reinforced by means of dry-stone supporting walls built just outside the entrance.

Well-preserved underground cave olive oil mills are still recognisable in several villages, modelled on the Roman style. Several of these are well-preserved. The Wadi Adrar organisation has a vision that these troglodyte oil mills could be restored, once again start producing oil, and become a tourist attraction.

Very little is known about troglodyte Mosques – mizghida – around the world, and no previous reports appear to exist concerning them in the Adrar Nafusa. Several such places of prayer have been found and studied during archaeological missions. This field of study needs further investigation. Some Troglodyte mizghida discovered by the Wadi Adrar Foundation contain inscriptions, including examples of Judean and early Christian symbols, that could shed new light on the historical background of the Jabal Gharbi area.

The area also contains examples of rock art, known locally as karita, which are found throughout the area, often outside the villages. These consist of Neolithic cup-mark petroglyphs intersecting straight incisions, which locals believe represented ancient maps of the neighbouring areas.

These areas of Berber history need to be preserved and restored for future generations. In so doing, they could become tourist destinations, helping the country diversify from hydrocarbons.

These architectural remnants represent a vibrant and beautiful part of Libyan culture but are now facing neglect and disruption. They deserve protection from UNESCO and could even be nominated as potential candidates for future World Heritage Sites. This would also encourage the development of a specific “Nafusi Libyan Berber” ethnic and social identity alongside that of the Amazigh.

Since 2003, ten academic papers have been published in scientific journals on these historical Berber ruins. Italian universities with interests in these sites are now working with Libyan professors from the University of Tripoli.

For more information see: http://www.wadi-adrar.org

http://wadi-adrar.academia.edu/ClaudioBencini/Archaeology-Papers [/restrict]