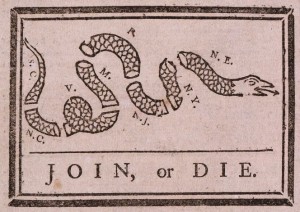

Join or Die: Part II

By Lorianne Updike Toler

London 28 February 2013

Although the 15th of February passed in peaceful celebrations across Libya, there is still a limited window of opportunity in which the various forces focused on Libya’s constitution can come together to successfully plan its process.

Tuesday’s announcement by the Libyan Supreme Court invalidating Amendment No. 3 of the Constitutional Declaration has resurrected the issue of elections versus selection for the Constitutional Committee. It remains unclear whether the General National Congress (GNC) will pass a constitutional amendment to finally decide the issue.

The GNC must address this issue with care to avoid introducing further procedural and legitimacy issues into an already beleaguered process. GNC leadership attributes much of the delays to their waiting upon the Supreme Court to finally decide the fate of Amendment 3.

Yet part of the delays thus far may be attributed to a failure to access all of the advice available to the GNC in a coordinated fashion from local and international experts. Additionally, civil society is unaware of the advice being offered, and therefore cannot judge how to advocate or hold the GNC accountable.

In an effort to help remedy the lack of information and to encourage greater coordination between the GNC, civil society, local experts, and the international community, this editorial will canvas the various constitutional efforts of the international community within Libya.

In relation to the international community, Libya is in a better initial position than other countries in post-conflict transition. In Bosnia (1995), Timor Leste (2002), Kosovo (1998), and Iraq (2005), the US and or the UN played dominant roles in constitution writing as part of the overall peace process. In each, sub-optimal results were produced. International heavy-handedness in constitution-writing resulted in what has been called a “shallow peace” between hostile ethnicities in Bosnia and a lack of local ownership in Kosovo. In Timor Leste and Iraq, international pressures dictated rushed timelines, yielding overly-political and incomplete constitutional settlements.

The Libyan revolution, however, produced a relatively decisive victory, pre-empting the need for any international peace-keeping forces within Libyan borders. Instead, Libyans stand to benefit from the expertise of the international community as Namibia (1990) and Albania (1998) did, should they choose to do so. In Namibia, the international community, including regional organizations such as the South West African People’s Organization and the Organization of African Unity, the UN, and the US help to establish and approve guiding principles that were subsequently adopted by the Namibian constituent assembly. In Albania, a model Libyans would do well to follow, the expertise of iNGO and local civil society organizations (CSOs) and experts was coordinated by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe for the constituent assembly’s benefit.

Although not coordinated as in Albania, GNC leadership seems most open to receiving advice from international organizations rather than any one country or international Non-Governmental Organization (iNGO). This because their advice is perceived as less biased.

The United Nations is one such organization, and is greatly respected by the GNC. The UN has multiple presences in Libya. Although the various organizations are independent from one another and report to different UN bodies, they all fall under the 2012 Security Council mandate to “lead inclusive political dialogue, promote national reconciliation, and determine the constitution making and electoral processes.” The United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL), the political mission, is supported in its engagement through complimentary programming by the country office for the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). UNSMIL provides technical constitutional and electoral advice and support at the request of the government and GNC. UNDP facilitates public dialogue and debate in the constitution-making process by funding CSOs, coordinating efforts, providing experts, working with Libyan academia, and directly managing awareness activities.

Unlike peace-keeping missions in other countries mentioned above, the UN treads lightly in Libya. They provide advice and assistance upon request. Recommendations are made but not pushed upon Libyan decision-makers. This political approach is due, in part, to a strategic decision by the UN to maintain a low profile, there is no need for an international military presence, and, as a state, Libya is financially independent. The UN’s self-restraint is of long-term benefit to Libyans, who will be able to self-determine their own constitutional path. A limitation of the relationship, however, is that the UN’s expert constitutional and electoral advice can be easily circumvented or drowned out by stronger advocates.

The EU also has a permanent political presence in Libya that coordinates programming implemented by its various organizations. Those EU organizations with a constitutional focus include the International Management Group (IMG) and the Network of Implementing Development Agencies, or EUNIDA. IMG, developed and funded by 13 member states plus Norway and Switzerland in 1993 after Yugoslavia’s demise, also has a strong presence in Libya. The country office has a small permanent staff of three with the flexibility to bring in experts on an as-needed basis, a budget of 4.5 million euros from contributing member states, and a mandate to be in Libya through 2014. They have a constitutional expert, but no electoral expert currently on staff.

IMG’s mandate allows them a greater advocacy role than the UN. They conducted induction training last Autumn for the GNC via a peer-to-peer programme involving Members of Parliament and 34 experts from European countries. They (in addition to the UN) also advocated for the GNC’s Public Affairs and Communications Department, established last November but not yet fully functional. According to Project Manager Elisa La Gala, IMG is also exploring helping the GNC to develop a constitutional civic education campaign through the newly-formed public affairs office as well as supporting the establishment of core functions of the Constitutional Committee’s Secretariat by the GNC.

EUNIDA’s constitutional programming includes helping to facilitate and fund a constitutional survey being conducted this month by the Benghazi Research Centre. According to Roland Hodson, Libyan Team Leader for EUNIDA, “poling is a very important part of modern democracy. If scientific poles can take place at multiple stages throughout the constitution-making process, the voice of the Libyan people will more easily be heard by the Committee of 60 in a systematic and comprehensive fashion.”

IDEA, or the Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, an intergovernmental organization with close ties to the UN and which supports democratic transitions globally, ran election-specific programming and constitution-related workshops in 2012. Although it had planned in its 2012-2014 budget to “provide technical support for the constitution building process” in Libya, its constitution-related budget expired at the end of January 2013. Whether this budget will be renewed in time to assist the Constitutional Committee remains unclear.

In addition to the UN and the EU, there are several iNGOs who have constitution-focused programming within Libya. These efforts are generally funded by NATO member countries—a logical extension of the military assistance provided by NATO in the Libyan revolution.

The Libyan office of the Public International Law and Policy Group (PILPG) is headed by well-known Libyan Fadel Lamen and is funded by a few NATO-member countries, including the US, the UK, and Canada. PILPG is a pro bono, Washington, DC-based law firm that specializes in providing legal assistance to officials and civil society members in states transitioning to democracy. PILPG in Libya advised the National Transition Council (NTC) and supported the drafting of the transitional justice law. It has also conducted over 30 workshops around Libya on the election versus selection debate and human and women’s rights for the legal community, women, youth and various local organizations. Now PILG will turn its workshop focus to the role of public participation in the constitutional process and support the development of a civil society-driven constitutional roadmap.

Democracy Reporting International (DRI), a Berlin-based iNGO whose Libyan funding comes from the British Embassy, has extensive experience in assisting and advising the Tunisian and Egyptian constitutional processes. Their Libyan constitutional programming to date has included workshops on the 1951 constitution and the essential elements of democracy with bar associations and faculties in Benghazi, Tripoli, and Misurata. Future programming will capitalize on DRI’s international network of comparative constitutional experts in authoring thematic briefing papers on the 1951 constitution, decentralization, interim constitutions, judicial independence and Islamic constitutionalism. Based on these briefing papers, DRI will host international experts to put on further workshops for bar associations, law faculties and CSOs. Other projects under consideration include training law students in methods of comparative constitutional research.

In addition to funding DRI, the UK Embassy has supported several Libyan CSOs through projects with Electoral Reform International Systems (ERIS) and DCA. ERIS is training and mentoring the Libyan Association for Democracy, which is collecting public commentary on constitutional issues, and Abshir, a group composed of former Thuwwar (revolutionaries) who helped to observe the 2012 elections and now are making plans to facilitate basic constitutional civic education for young men who fought in the revolution. DCA provides subgrants for women’s groups, some of which is going towards constitution training and awareness-raising activities. The Embassy has also provided funding for the National Democratic Institute, who has in turn provided support for a national youth network advocating a 10% quota for youth involvement in the Constitutional Committee. Finally, the British Embassy funded BBC Media Action to train and support al-Wataniyah and Official Libya TV, and the Institute of War and Peace Reporting to work with 15 community radio stations to help Libya’s media outlets provide discursive and informative programmes on Libya’s transition, including the constitutional process.

The German Embassy recently supported The Voice of Libyan Women’s One Voice conference, held 26-28 January. In preparation for the conference, the organizers authored a comparative analysis of how women’s issues such as marriage age and maternal transfer of nationality are constitutionally addressed within the region. During the conference, a workshop was staged in which recommendations regarding key constitutional process issues were proposed by conference attendees. The Swiss Embassy has funded similar constitution-related workshops.

The remaining iNGOs with a constitutional focus in Libya are funded by the United States Congress, including the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the United States Institute for Peace (USIP), and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). USAID, through their Office of Transitional Initiatives, provides grassroots-level support and small grants to Libyan organizations especially in less-served areas. Constitution-related projects of this nature include USAID trainings around the country for civic groups on constitutional issues, state structures and advocacy. These trainings resulted in CSO activities such as conducting constitutional information dissemination campaigns, performing surveys of low-income areas of Tripoli to use in crafting better-targeted constitutional education materials, and advocacy campaigns on constitutional issues. Other programming includes funding a constitutional bus tour staged by H20 (discussed at more length in the first article in this series); producing Public Service Announcements, radio spots, short videos, and pamphlets on constitutional issues; and providing physical space, particularly in the South and East, for citizen-government dialogues and the production of constitutional civic education literature.

USIP, which has produced some of the most comprehensive research in constitutional process, has provided the expert support backing the network of 500+ Libyan CSOs advocating what is called the “manifesto.” This document calls for a transparent, participatory, and inclusive constitutional process and is discussed in more detail here. Those coordinating the network are individually funded through Angelina Jolie’s Jolie Legal Fellows Initiative.

NED, in keeping with their practice in other transitional countries, is supporting local Libyan CSOs and offering expert transitional assistance in response to local needs and demands, and is currently looking to expand its support to Libyan CSOs engaged in constitutional process and substance. NED also supports two regional organizations with Libyan participants or partners focused on constitutional issues, the Project on Middle East Democracy (who in turn support some of H20’s programming), and the Right to Non-violence out of Lebanon headed by internationally renowned middle eastern constitutional expert Chibli Mallat.

In short, Libya has the support of many international organizations and foreign governments in educating its citizens about constitutional substance and process through local civil society organizations. (Of course, many Libyan organizations working on constitutional issues are not on the international community’s radar.) Whether those in power will likewise take full advantage of the international expertise on offer, however, especially in a coordinated fashion like Albania’s, remains yet to be seen.

Danielle Tomson contributed to this report.

This is the fourteenth editorial in a series on constitutionalism authored by constitutional legal historian Lorianne Updike Toler, founding president of The Constitutional Sources Project and Lorianne Updike Toler Consulting. [/restrict]