By Lorianne Updike Toler.

New York City, 2 November:

The necessity of separating governmental power may be all too familiar for Libyans, recently . . .[restrict]freed from Muammar Qaddafi’s all-encompassing control.

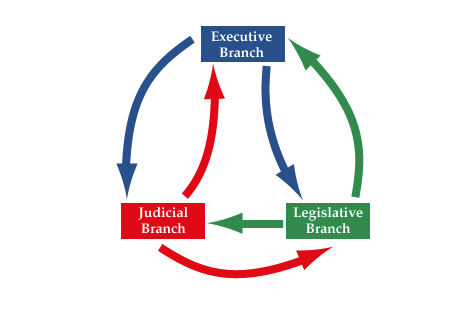

Libya’s current transitional parliamentary system incorporates more separation of power principles than Qaddafi’s authoritarian rule, but the extent to which it allows the kind of true independence with accompanying checks and balances between branches usually implied by a reference to “separation of powers” has recently been a matter of some debate among members of the National Congress as well as many political observers in Libya.

The quick switch in prime ministers-elect and the rejection of Mustafa Abushagur’s government on 7 October caused many to question whether there is currently sufficient separation of powers in Libya.

As was laid out in the last article in this series, the procedures the General National Congress followed were precisely according to constitutional design. The constitutional declaration of August 2011 failed to clearly delineate where the National Transitional Council’s executive powers ended and where those of the transitional government began, leading to not inconsiderable confusion on a number of occasions. This problem has not been resolved with the emergence of the new government and Congress. The constitution does not specifically identify separate roles for the new legislative, executive and judicial powers; it merely requires that ministers receive the confidence of the GNC.

As Libyans consider the structure of their current system and possibilities for a new constitution, “separation of powers” concepts and principles require a more in-depth discussion than they have as yet received in Libya.

Here, the history of “separation of powers” ideas will be provided and then applied to the GNC’s constitutional design. Future articles to immediately follow in this series will compare how separation of powers ideas have been applied in other states.

“Separation of powers” in Middle Eastern, pre-Ottoman cultures was not necessarily explored conceptually as much as it existed as between ruler and ulama, muftis, and q???s. Instead, the roots of “separation of powers” as an idea are found in Antiquity. Plato identified five types of government, which Aristotle whittled to three—democracy, oligarchy (rule by the few, often by the aristocracy), and monarchy. The best constitution, according to Aristotle, combined many forms of government.

The Roman Republic, which embraced modern-day Libya for 102 years, implemented Aristotle’s idea by combining the three forms of a government into a Senate (aristocracy), Assembly (democracy), and various magistrates such as consuls, praetors, aediles, and tribunes (monarchy). Polybius, a Roman historian, was the first to advocate that, once a government was mixed, its powers must be separated. Thus was born the concept of “separation of powers.”

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the idea and its practice were received in Europe more than 500 years later. This through the rediscovery of Roman Law in a university in Bologna, Italy, and the eventual transmission of Greek ideas, made possible by the preservation work of Arab scholars.

With the age of the Enlightenment, scientific methods were applied to the practice of politics. Philosophers translated ancient ideas of “mixed” and “separated” powers into more modern terms. Instead of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy, people began to speak of executive, legislative (combining both aristocratic and democratic elements), and, eventually, a judiciary.

John Locke, an English philosopher, wrote in 1689 that separation of powers was needed to prevent power grabs. If the same people were allowed to create and execute the laws, the would be tempted to “exempt themselves from Obedience to the Laws they make, and suit the Law, both in its making and execution, to their own private advantage…”

The French philosopher Montesquieu agreed. In his 1748 Spirit of the Laws, he wrote: “When legislative power is united with the executive power in a single person or in a single body of the magistracy, there is no liberty, because one can fear that the same monarch or senate that makes tyrannical laws will execute them tyrannically.”

Amassing power in one individual or body can also result by combining judicial with executive or legislative power. Montesquieu wrote: “Nor is their liberty if the power of judging is not separate from legislative power and from executive power. If it were joined to legislative power, the power over life and liberty of the citizens would be arbitrary, for the judge would be the legislator. If it were joined to executive power, the judge could have the force of an oppressor.”

According to English jurist Sir William Blackstone, preventing combinations of powers was a matter of providing various branches, or divisions of government, with negatives upon the other. Such negatives needed to be “sufficient to repel any innovation which it shall think inexpedient or dangerous.”

American Founding Father James Madison in Federalist 51 added that “ambition must be made to counteract ambition” in creating a system of checks and balances.

To do this, first, each power must be given a will of their own. Second, the ability to appoint other branches’ membership should be limited as much as possible where popular elections is not possible or advisable. Third, each power should be as independent as possible for the privileges and salaries of their offices. Men are not angels, requiring a system of government where they are be compelled by co-equal branches to govern themselves.

Does the GNC match up to these ideas? In part. As will be discussed in a following editorial, all parliamentary systems are not fully faithful to the conception of true independence between branches. In fact, the executive (the prime minister and his cabinet) is fully dependent on the legislature for their positions and maintained in office through parliament’s confidence. Abushagur was frustrated by this dependence when he and his cabinet were rejected by the GNC.

Yet this is not to say that parliamentary systems such as Libya’s do not maintain any separation of powers. Ali Zeidan resigned from the GNC in order to run for prime minister. Coordinately, his proposed ministers are not members of the GNC. If separateness is judged by maintaining separate personnel in separate bodies, Libya should receive good marks. Too, in Madisonian style, the government and GNC should each presumably have “wills” of their own to pursue policy choices.

Although it could be characterised as a dependent relationship, the GNC’s power in approving and maintaining the government may be viewed more as a heavy-handed “check” on the power of the executive. This will invariably prevent any prime minister and surrounding cabinet from becoming too powerful, or Qaddafi-like one might say.

Danielle Tomson contributed to this editorial.

This is the third in a series of weekly articles wherein constitutional principles and procedures of various countries will be examined and compared in-depth. [/restrict]