By Nour Naas.

Tripoli, 2 September:

From the very beginning of the 17 February Revolution, the tricolour flag with the crescent and star . . .[restrict]has been its rallying symbol. But it is a symbol that has its own story — one that speaks of an earlier struggle for Libyan freedom and unity, an earlier struggle that likewise saw Libyans die in their thousands for freedom.

It is estimated that over 100,000 Libyans died during the Italian colonial period. Most perished in the desert, fleeing on foot to Egypt, seeking safety from the Italian forces intent on suppressing the resistance movement in Cyrenaica led by a humble teacher, Omar Mukhtar. He ran the military forces of the Senussi movement, headed from his exile in Egypt by Sayyid Muhammad Idris Al-Mahdi Al-Senussi.

Not that the he or they would have identified themselves as Libyans. The name was a recent Italian colonial reinvention. The Italians had decided to run their two colonies of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica as a single colony and needed a name for it. They revived the name of Libya, which had not been used for some 1300 years.

But if the name meant nothing, freedom did.

On 24 December 1951, 20 years after Mukhtar’s execution by the Italians, Libya became an independent kingdom with Sayyid Idris its first and only king. The country had gained its freedom —and by then the named was ingrained in people’s minds.

A close colleague and friend of the king was Omar Shennib. He became the new Minister of Defense, Vice President of the Libyan National Assembly and Chief of the Royal Cabinet — although not for long; he died in 1953.

Shennib too sought to unify the three entities that made up what was then a federal state Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzan – into a single nation and under one flag. In fact, he designed the flag.

Last month, just a few days before his tragic death, Majid Wanis, grandson of Shennib and son of Wanis Gaddafi, the last of King Idris’ prime ministers before Muammar Qaddafi (no relation) seized power in 1969, explained the meaning and symbolism of the flag to the Libya Herald.

Tripolitania, the northwest region of Libya is in terms of size the smallest of the three historical regions of the country. When in 1918, a group of local leaders declared their Tripolitanian Republic, they chose as its flag a green palm tree with a star above it against a light blue background. The Italian colonists had much the same flag for Tripolitania, except the blue was darker and there was a golden band underneath and a crown above.

Under the Ottomans, however, Tripolitania had had a green flag with three crescent moons.

Fezzan only came into existence as a separate state in 1943 when the French took it over; previously under the Italians and the Ottomans it had been administered from Tripoli. Under French rule, it had a red flag with a white circle containing a crescent and a star.

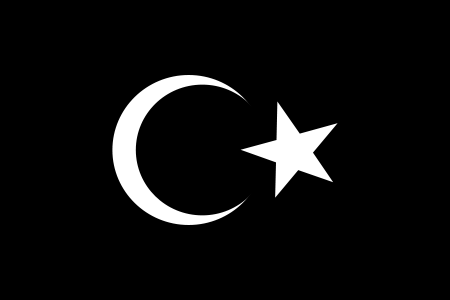

The Emirate of Cyrenaica, declared as a British protectorate in 1948, had a black flag with a white crescent and star at the centre.

These flags became the basis for the flag of the united country.

According to Wanis, the new flag was intended to represent a bond between the Libyan people – from all regions into one.

But the green for Tripolitania, black for Cyrenaica and red for Fezzan meant more. Shennib wanted to honour the martyrs, treasure the freedom so many had fought and died for, and stress the country’s faith, Islam.

So the red is there to represent the blood of those thousands of earlier martyrs. The green symbolises everything the people fought for – their freedom and independence. The black with the crescent and star represents the Libyan people’s way of life – Islam. It more than represents Islam. The first black flag used for Cyrenaica was an actual piece of the black cloth that covered the Kaaba in Mecca, to which the crescent and star were added.

On September 1, 1969 Muammar Gaddhafi seized power. The monarchy was abolished, the country’s name changed to the Libyan Arab Republic and the old flag thrown out. The new one was similar to that of Egypt. About one year after the military coup, Libya’s flag was changed again, to that of the Union of Arab Republics which Libya had joined.

Then, nearly eight years later, Qaddafi changed the name of the country to the Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya. The flag was changed once more to solid green.

Since mid-February, 2011, the Kingdom of Libya flag proudly flies. Libya’s former green flag is despised because of its associations with Qaddafi’s Green Book and all his other “Green” ideas that, during the much of his rule were obligatory for school children to study the book at least two hours per week.

That flag now symbolizes, in most people’s minds and hearts, resistance to the oppression not of the Italians but of the Qaddafi regime, and the freedom that started on 17 February last year when thousands marched the streets, demanding for the fall of the regime, when civilians became rebels, journalists and freedom fighters overnight.

Living under dictatorship; ruled by an iron fist; watched by Qaddafi’s secret guards; obliged to attend the hangings in university gymnasiums for people who only spoke out against the government; family members massacred in Abu Salim prison; Italians and Jews expelled from the country in the 1970s; school children taught to glorify Qaddafi; pre-Qaddafi history erased from people’s memories. This and so much more was the reality of the regime. Everyone in Libya has been negatively affected by Qaddafi’s reign.

Living under dictatorship; ruled by an iron fist; watched by Qaddafi’s secret guards; obliged to attend the hangings in university gymnasiums for people who only spoke out against the government; family members massacred in Abu Salim prison; Italians and Jews expelled from the country in the 1970s; school children taught to glorify Qaddafi; pre-Qaddafi history erased from people’s memories. This and so much more was the reality of the regime. Everyone in Libya has been negatively affected by Qaddafi’s reign.

In the early 20th century, Libyans, such as Omar Mukhtar, began to resist Italian rule. For nearly 20 years they fought, and now just over a century after Italians colonized Libya, Libyans are fulfilling the aspirations of their grandparents and great-grandparents. Qaddafi deprived the Libyan people of their roots, determined to make himself all that they would be able to remember. History was erased, heroes vanished and, as the generations went by, the past forgotten. But during last year’s revolution, the heritage of Kingdom of Libya was revived – its flag, its anthem and the opportunity to learn.

Between 1969 and 2011, the oppressor was different, but the meaning of the flag remains the same: our blood, the darkness, Islam and our freedom. The red continues to represent those who were martyred fighting for the people and the right for our country to be free. Black stands now for 42 years of oppression. The central crescent and star represent Libya as a Muslim country. The green band now serves as a reminder of the Qaddafi regime, from which the country is now, thankfully, free. Red, black and green – the tricolor flag that hangs on our roofs, is engraved in our hearts, and will forever be stained with the blood of the Libyan people.