By Andrew Gold.

Arlington, VA, 7 July:

Anyone standing in the lobby of the Holiday Inn in Arlington, Virginia, this week would have . . .[restrict]heard clapping, cheering, and zaghareet — the traditional, high-pitched ululation common in North African cultures — coming from a banquet room down the hall. The average passerby, however, might not have guessed that that the celebration was for people casting ballots in an election.

“This is our wedding — a Libyan wedding,” said Ahmed Shaltami, who came from Ohio with his family to vote in the first Libyan general election in several decades. Though he and many other Libyan-Americans were disappointed that there was only one location in the whole of the US where out-of-country voters could participate, Shaltami was still overjoyed.

“It’s overwhelming,” said Mohamed Saeed, who was born in Tripoli, raised in Benghazi and left Libya in 1974. He has since lived in the southern US, where for decades he watched Americans vote regularly and often unremarkably, knowing that he could not do the same back home. Many of his relatives, Saeed said, had been locked up for years for speaking out against longtime dictator Muammar Qaddafi, and when the uprising began last year, one of his sons joined the rebels and was in Sirte when the former ruler was captured and killed. Despite his concern with the security situation in Libya, Saeed was generally optimistic for the future.

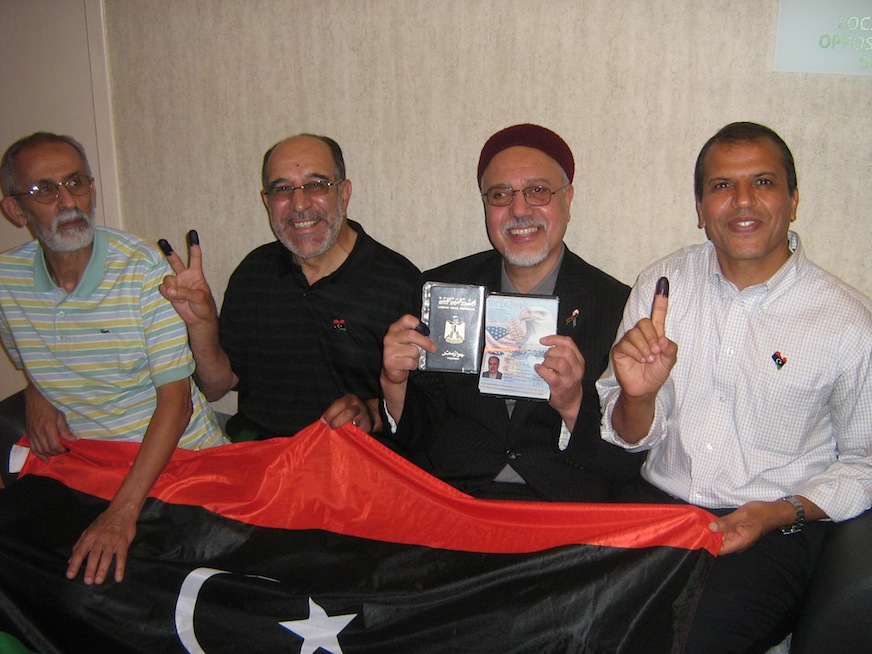

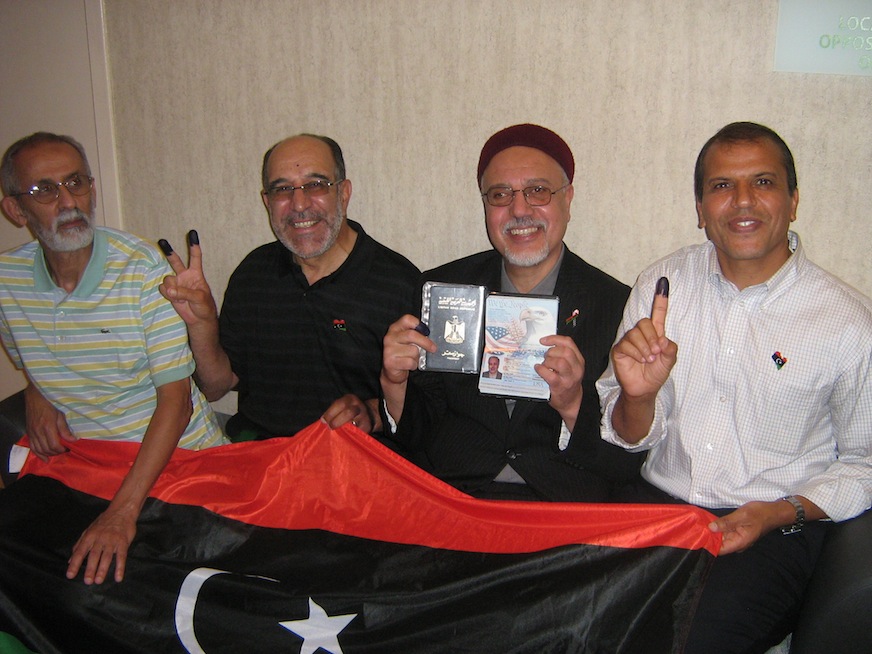

Libyan-Americans have been coming to the hotel in downtown Arlington from seemingly every corner of the country in a steady stream throughout the week to participate in the first general election in Libya in over forty years. For some, it is the first time in decades they have practiced any form of democracy in their country of birth. Younger participants have only known a Libya dominated by Qaddafi. Poll workers remarked that there were many tears on the first day of voting here on Tuesday.

When voters arrive, they are greeted and directed to an informational area, where they can review the majoritarian/proportional scheme of voting, look at the full list of parties and candidates, and view a map of Libya’s electoral districts. Once each participant is ready to vote, they must present proof of citizenship to poll workers, go behind a booth to mark their ballot, cast it into a box, and then dip their finger in ink.

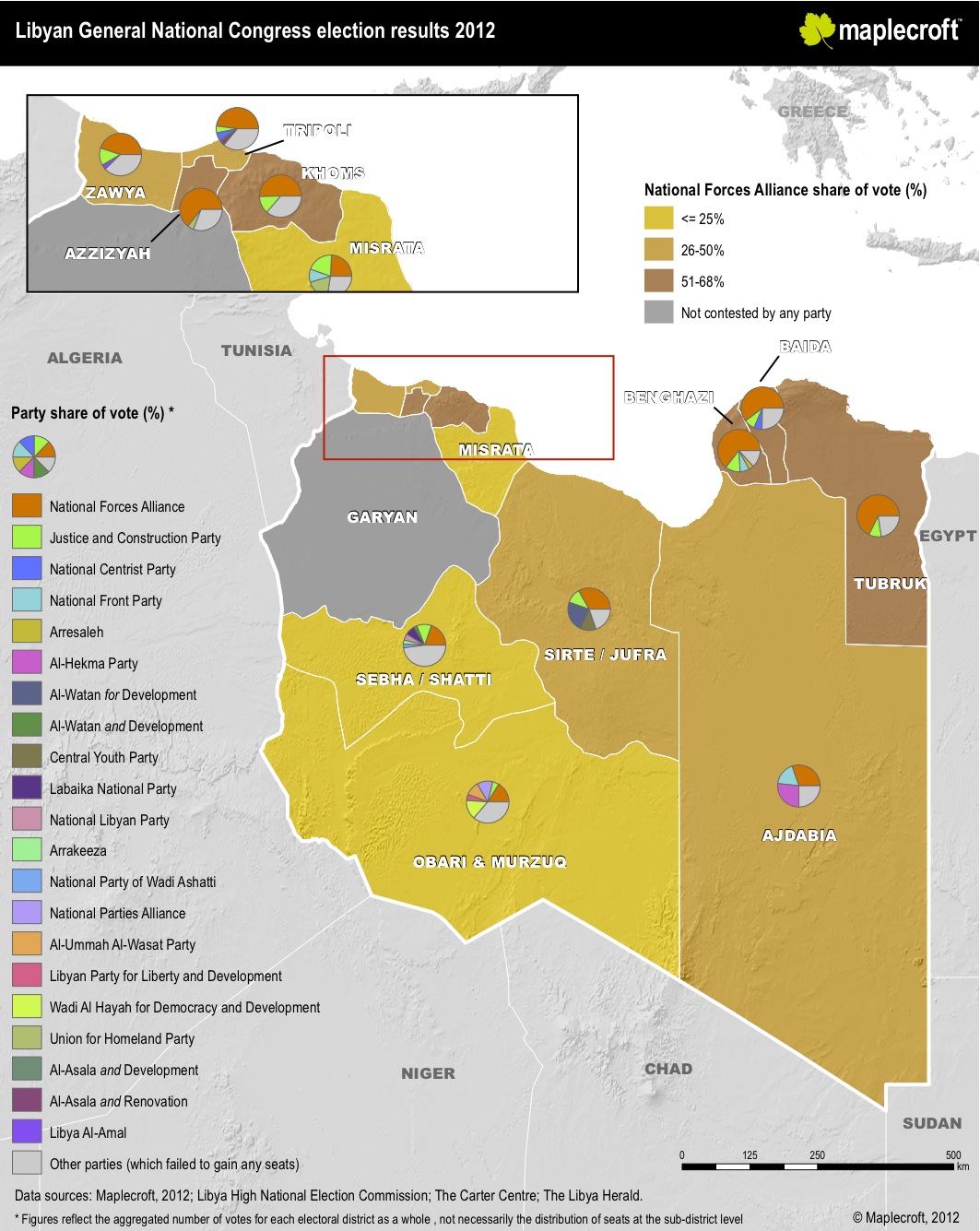

Out-of-country voters in this election enjoy the freedom to vote for candidates in any electoral district they want, as opposed to in-country Libyans, who must vote according to the region in which they live. As a result, many voters have been voting for candidates in the regions they originally hail from, and saw their votes as being for family members still in Libya as much as for themselves.

Ibrahim Dabbashi, one of the Libyan diplomats who in February of 2011 publicly came out against the Qaddafi regime, was present on Saturday, and was optimistic for the future, despite security concerns and some recent violent incidents, including the downing of a helicopter in Libya carrying election materials on Friday. “If we succeed today, we will succeed in the future,” he said. Sami Swadek, a former diplomat who in 1984 defected from the regime while posted in Geneva and sought political asylum in the US, said the experience of voting in a general election was like a dream. His daughter was with him, and likened the coming days in Libya to a blank slate: “It’s an opportunity to start fresh.” [/restrict]