By Umar Khan.

Tripoli, 6 July:

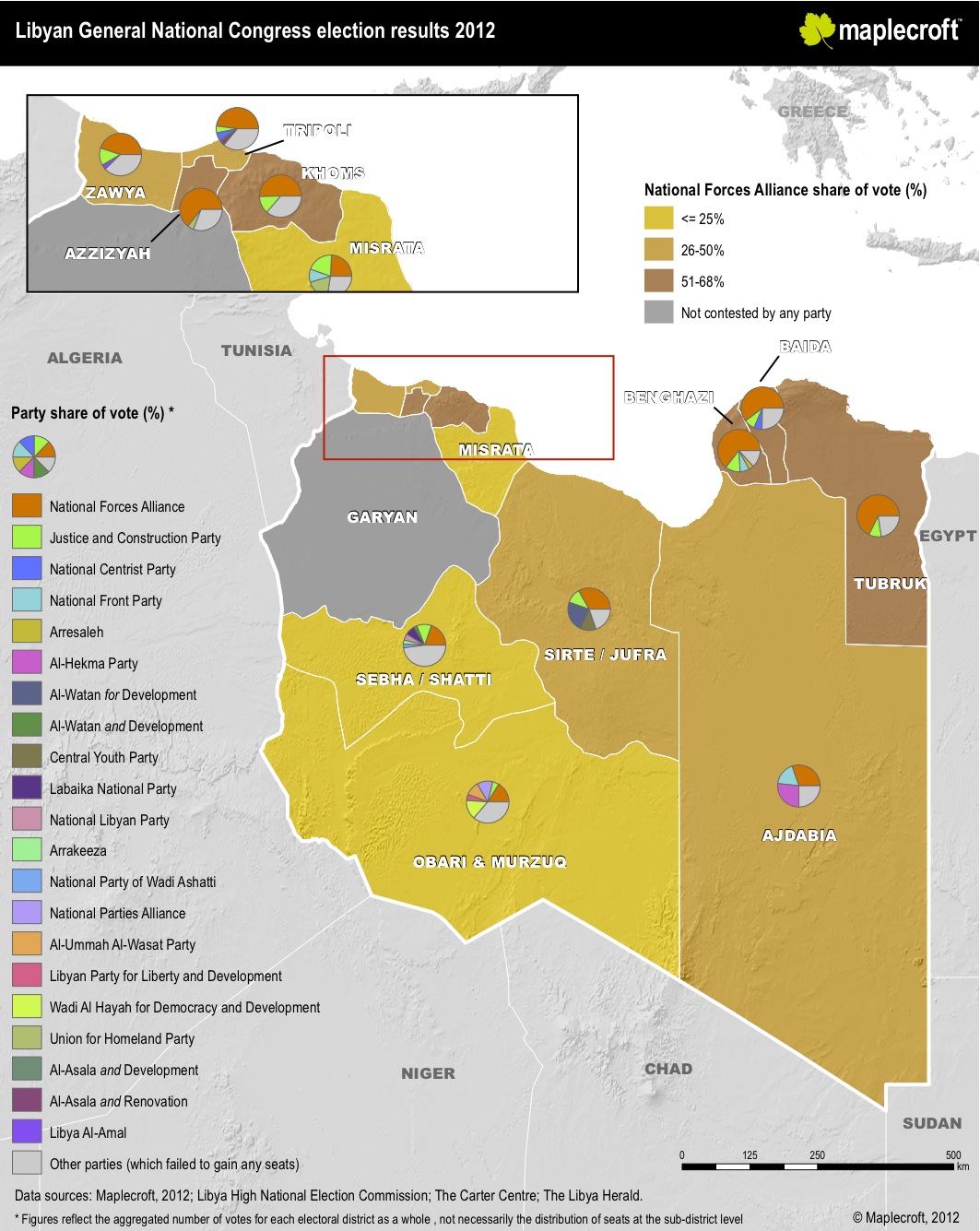

The campaigning for the first elections of Libya . . .[restrict]in more than four decades ended on Thursday evening with two major parties, the Justice and Construction Party and the National Front, holding rallies in and next to Tripoli’s Martyrs Square respectively. Turnout for both was surprisingly low.

Party campaigning has been a new experience for the majority of the population, if not all. After watching the same face on all posters and billboards for almost 42 years, the sight of thousands of different faces across the country was confirmation for almost everyone of the changes that Libya has been through over the past year.

There was relatively little effort by many party candidates to interact with voters directly to explain policies and plans. Some individual candidates, however, as well as a few on party lists made the effort to reach out to voters by taking part in public meetings and other interactive events. The campaigning for most, however, meant only putting up huge billboards and posters around their constituencies although many had websites and used social media such as Facebook and Twitter.

The lack of political exposure ensured that in many cases voters remained confused. The fact that campaigning was limited to 18 days did not help either.

The main cities were bombarded with posters of different candidates and party logos from the very first day although not all parties started campaigning from Day 1. Most parties suffered technical and logistical problems simply because of their lack of political experience and skills.

The campaigning by different parties, like their manifestos, was much the same. All had a media event to launch their campaign and concluded with a big public event. The success of the campaigns varied from party to party and depended on the scale of effort invested. Some individual candidates did nothing more than put up a few posters.

The focus in the main towns and cities by the parties inevitably meant that smaller towns were neglected while in some cases, such as in Bani Walid and Kufra, the campaigning never really took off in the first place — but that was because of special local circumstances. The post-liberation clashes, poor security situation and the current standoff with the government over the refusal of Bani Walid to handover wanted people, restricted the candidates there from holding any major public events.

However, Tarhouna, another city often viewed as a safe haven for Qaddafi loyalists, was taken over by election fever. Unlike Bani Walid, public events were held by many different candidates with political parties also holding open events to explain their program.

The key issues for all the parties during the campaign were identical — such as reconciliation, security and the role of the national army, the Sharia as a source for legislation, federalism and justice. The big difference between the parties was not policies but personalities.

The most aggressive campaigns around the country were run by Mahmoud Jibril’s National Forces Alliance, the Nation Party and the Justice & Construction Party in terms of the number of posters, flyers and billboards and the number of public events. However, no party was able to gather particularly large crowds for any of the events.

Libyans’ keenness to vote and yet reluctance to take part in any political activity is attributed to the lack of any previous political experience. During the time of King Idris some parties were allowed to operate but all were banned by Qaddafi who went as far as ruling that anybody who set up a party was a traitor.

Umar Khan can be found on Twitter at www.twitter.com/umarnkhan

[/restrict]