by Sharon Lynch

“You know, Sharon, every time I remember that the elections are coming I feel so sad, I get . . .[restrict]scared….I never voted before….I don’t know how it is supposed to go, and it’s coming, time is passing. The sad thing is that most Libyans are like me.”

Catching up on Skype earlier this week with a young medical student from Tripoli, I was surprised when the conversation turned to elections and she told me “you know, Sharon, every time I remember that the elections are coming I feel so sad, I get scared…. I never voted before.” When asked why, she revealed: “I don’t know how it is supposed to go, and it’s coming, time is passing. The sad thing is that most Libyans are like me.”

I reminded her that Misrata, Zuara, Qa’ala, Tajoura and Al-Abyar had all held elections. Even with the flurry of articles in the press about the Misrata elections, it seemed she did not understand how the election process worked nor did she realise what having the election meant to Misratans. This article is meant to demystify the process and demonstrate that elections are not only doable — and decidedly not scary — but good for the soul. I hope reading the story of Misrata’s elections will help her and other Libyans feel less overwhelmed by the prospect and better understand how to help their communities move forward with their own elections. As Misrata showed, voters can be registered, candidates qualified, campaigns run, votes made and counted, and winners declared in as few as twenty-one days.

While reading articles congratulating Misratans for their highly successful election last week, I became curious about how the new voters decided how to cast their votes. I also wondered why not one of the three female candidates who ran won a seat. Reaching out across Twitter and speaking with Misratans, I learned answers to these questions — and more, concluding that there are some valuable, and possibly some difficult, lessons to be learned from Misrata’s remarkably well-designed and orchestrated election process.

Mohamed Berween, a professor of political science and department chair at Texas A&M University in the United States, borrowed from the best practices of the American and European systems he had been teaching to students for decades, to design an election road map based on universal suffrage and transparent, fair processes. His mandate was to show the “rest of Libya and the international community that Libya can govern itself and Libyans are qualified to live as human beings with dignity and stability.”

Berween aimed to prove it was possible to have successful elections in a short time period. In the course of twenty-one days, he and a small team of volunteers made it possible to register 101,486 voters — 65 percent of the eligible voting population — as well as process applications for 245 candidates, set up polling stations in ten districts and manually count close to 60,000 votes in time to announce 28 winning candidates the next day. All of this was done with complete transparency, open meetings and in the presence of election monitors.

A realist, Berween acknowledges that compromises were necessary to achieve this objective, philosophically reflecting that life itself is based on compromises. Lacking complete census data, the first compromise was to use the districts that had been drawn in earlier years. Berween was acutely aware of the complex political issues involved with districting in the state of Texas where he had lived for the past 33 years and did not want to complicate this election by redrawing districts and inviting similar problems. He also recognised that it made sense logistically and would facilitate the comfort level of the voters to work with election districts based on districts Misratans already knew.

Qualifications to vote were purposely kept simple: to register you had to be Libyan, at least18 years old and prove residency. The goal was inclusive, universal suffrage.

The criteria for candidates were also designed to make it possible for any resident of Misrata to run. When filing an application each candidate was required to be at least 25 years old and not have been associated with regime leaders. There was no educational requirement and there was no fee, allowing people of all income levels to declare candidacy.

However, each candidate was required to ask twenty people, of at least 25 years of age, who were not first or second degree relatives, to personally endorse him or her before a three-person committee, swear on the Quran and sign an oath. Twenty-six candidates of the original 245, including one of the original four female candidates, were disqualified. Fathi Seid, a Misrata meterologist and telecommunications specialist, described how a friend was disqualified when one of his endorsers turned out to be younger than 25. He was given an opportunity to correct the problem but decided instead to withdraw his candidacy. According to Seid, one candidate from the local council that took Misrata through the war was disqualified because of his ties to the former regime.

Two hundred and nineteen candidates, including three women, campaigned for election during the four-day period prior to election day. The oldest candidate was 71 and the youngest, 25. Candidates campaigned by hanging posters displaying their photographs, curriculum vitae, age and other qualifications. Some posters included campaign slogans about care of the wounded, democracy and rebuilding the city. All of the candidates were well known throughout the community.

On 20 February, election day, polls were scattered across districts where men and women voted separately. Seid remarked on how in his district, the most densely populated of the ten, there were fifteen polling stations, each of which had separate areas for men and women to vote. The day was declared a public holiday, with schools and businesses closed, and the polls were open from 8 am to 8 pm. Proudly observing that his polling station was not crowded, Seid reported that it took “only five minutes to vote”.

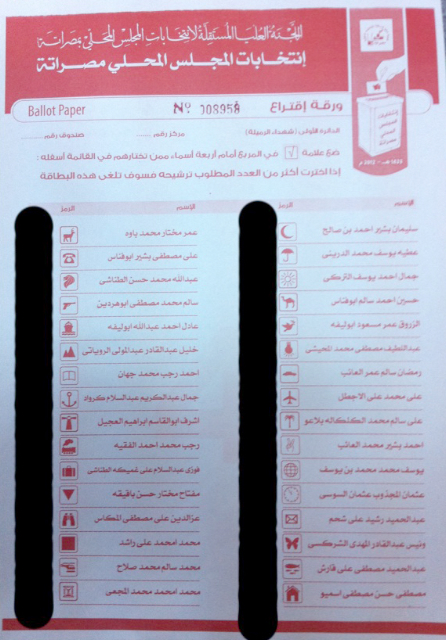

Voters in the Shahada Arrumalia district chose four candidates from a list of 43. On the ballot form, candidates were listed in the order in which they filed their applications. Berween explained that listing alphabetically would have discriminated against those whose names began with letters from the bottom of the alphabet, as voters tend to vote for candidates closest to the top of the list. Listing candidates according to the date applications were filed also provided incentive to get involved in the race early. As a premium, pre-drawn symbols were offered to the first 50 candidates to file candidacy.

According to Seid, the instructions about how to vote were clear and the process was easily navigable. After being cross checked against the list of registered voters, you voted privately in an election booth, folded the ballot twice – as illustrated on the ballot from the Shahada Arrumalia – and dropped it into the ballot box. You then dipped your finger in blue ink to show that you had voted and the process was complete.

On 21 February, the day immediately following elections, Berween and his team announced the winners of the 28 council seats including the number of votes earned by each. This information was also posted on Misrata’s election website (http://www.lecm.ly/?p=204).

Noteworthy winners included Ibrahim Abdussalam Mohamed Safar and Mohamed Mukhtar Mustafa Ben Othman. Safar, who topped his district of That Al-Rimal, was wounded during the war and ran on a platform of helping the injured. Ben Othman was the only candidate to remain from the council that ran Misrata during the war. According to Libyan academic Faraj Najem, he was also the only Muslim Brotherhood candidate to win a seat.

Conspicuously noticeable was that not one of the three female candidates won a place on the council. When asked why he thought none of the women were elected, Berween suggested that the competition was fierce, explaining that one of the districts in which they ran included 43 candidates, the other 28. Berween astutely pointed out how many years it took for women to hold seats in the United States Congress and how even now, they only make up 11 percent of the Senate. Excited by their candidacy, he told each of the women she had won just by running and strongly encouraged each to run for election to Libya’s national constituent assembly in June.

Iqbal El-Barat, a Misratan who just finished her masters degree in computer science in the US, wondered if perhaps the women did not win because, during the war, most women remained inside the home and consequently female candidates may not have been as readily recognizable as the men.

Fathi Seid’s response to why he thought none of the women won, was to ask me: “Why isn’t Hillary Clinton president of the United States?”

Recent graduate from the Misrata Faculty of Arts Fadwa Faisal agreed with Eldaarat that most voters would not have been as likely to know the female candidates as their male counterparts.

She also offered another perspective. She chose pointedly not to vote for a woman, even though one of the women who ran in her district had been her professor. Even while she had three votes, she only used two, when the third could have gone to a woman. Faisal took a lot of heat for her position from other Misratan women, but she emphatically and thoughtfully explained her decision, saying first that she was not going to vote for a candidate simply because she was a woman. Secondly, she did not see women in general as well enough qualified to meet the immediate and substantial challenges of rebuilding the city. Faisal views Misrata as needing time to grow and flourish, “to go to the top” under the guidance of someone more experienced who has successfully taken on similar responsibilities. Her recommendation to women was to “wait six months more and then run” after Misrata is past this critical time.

Faisal also shared information that might encourage more women to run for office: she was told that one of the female candidates missed being elected by just a few votes. Given that women made up only 39 percent of those registered to vote and 36 percent of those who voted, coming this close to winning in the first election in a conservative city like Misrata is a significant accomplishment.

Several days after election day, the newly elected council members met for two hours to elect a chairman and vice-chairman. Like all of the meetings regarding the election, it was an open meeting and this one was televised. Each of the six to seven members vying for a leadership role spoke for two minutes presenting his views. It took three rounds of voting to determine who would take on these positions.

In the end, the council voted the enormously popular and well-respected Yousif Mohamed Ben Yousif as chairman and Mohamed Al-Hadi Hasan Al-Jamal as vice-chairman. Both campaigned on platforms based on unity and rebuilding the city. Ben Yousif is considered a young man by traditional Libyan standards for officials. Al-Jamal, even younger, appears to be in his late twenties, early thirties.

Berween, Seid, Al-Barrat, and Faisal all praised Ben Yousif and welcome his leadership. Ben Yousif is recognised widely in Misrata for his critical role during the war. He returned to Misrata from Dubai, bringing medicines, food and other supplies, and supported the war effort financially. Al-Jamal is considered to be very well-educated, similarly capable and also “there” during the war. Five other council members joined Ben Yousif and Al-Jamal on the executive board: Saleem Bait Al-Mal, Fathi Shawat, Ibrahim Safar, Ramadan Ben Ruween and Atiya Al-Dreini.

The references to Ben Yousif’s and Al-Jamal’s contributions to the war effort are telling. According to Eldaarat and Seid, when Misratans went to vote, the primary criterion they considered was how candidates had proven their support for Misrata during the war. Also scrutinised were the level of education and prior experience offered by the candidates. In a city closely knit in the aftermath of the war, all of the candidates were well known. Eldaarat told me how her family and neighbors took their civic responsibilities seriously, talking among themselves up right up until election day in animated discussions about the candidates’ qualifications. With excitement in her voice she declared, “I like it!”

Seid was concerned with education level. Like Faisal who refused to allow her vote to be dictated by gender or pressure from other women, Seid purposefully divulged how he — and his wife and daughter — did not vote for his own brother-in-law because they thought there were other better-qualified candidates.

To say Misratans are happy with their election would be an understatement. The voices of every person with whom I spoke were luminous with pride. Berween talked about how elections were about the beauty of being human. So moved, he cried for the first time in his life in front of thousands of people on television. The civic-minded Seid joins his friends each evening at the café where a week later they are still discussing the elections and generously answering the questions this writer tweets to him.

Eldaarat related how her mother and father described their first time voting as a “very exciting experience” — they were “free to express their opinions, completely free” and unafraid. At the polls people were friendly, even though they might be voting for a different person. Amazed at how well organised the “very safe, very nice” elections were, Eldaarat summed it up: “Finally we saw happening in Libya what we had seen on television in other countries!” adding, “everybody is happy. This is an honest election. No one in Misrata is complaining at all.”

Faisal said it simply. When I asked her what she thought of the election she declared “well, it was such a great feeling… I felt so human.” She told me how when she went to vote she was a bit overwhelmed by the responsibility of the decision she had to make. She noticed some women were crying and when she asked why, they willingly confessed how “they never thought it would be such a great day to vote for what they want.”

Questioned if the Misrata model would be used in the national and other local elections, Berween modestly declined to reply, saying that his team had created a road map for others to use but he could speak for Misrata only. However, as Berween himself suggested, compromises were made in order to move forward quickly and compromises by nature suggest improvements. A teaching experience for the rest of Libya, there are lessons to be learned from the Misrata election.

© Sharon Lynch

This is the first part of Sharon Lynch’s article looking into the Misrata election. The second part will be published on Wednesday.

[/restrict]