By Umar Khan.

Tripoli, 11 August:

Under Muammar Qaddafi, Libya was one of the most restrictive countries in the world when it came . . .[restrict]to free speech. With the regime’s collapse last August, the road finally became open for those who had opposed Qaddafi for so long to tell their side of the story.

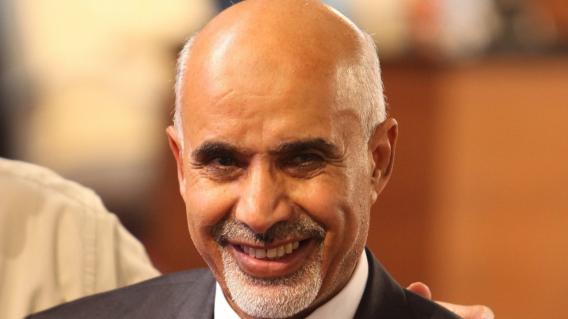

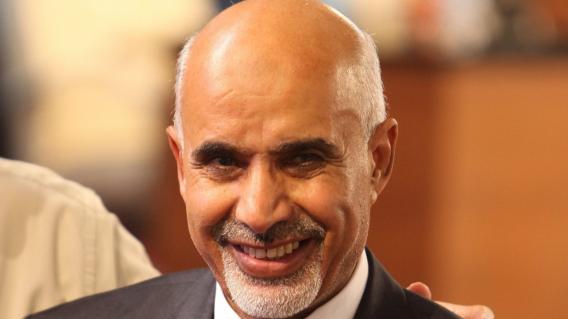

There are countless people who have a story to tell, but that of Mohammed Yusuf Magarief, the newly-elected Speaker of the National Congress, stands out because of its depth.

Magarief’s relationship with Qaddafi started just two years after the dictator came to power in 1969, and ended with the latter’s death 39 years later. There were several attempts on Magarief’s life by Qaddafi’s agents during this period, most famously the downing of a UTA airliner over Chad in 1989, which cost the lives of all 170 people on board.

Seen as the symbol of resistance for over 31 years, Magarief began his struggle when he publically announced his opposition to the regime in 1980.

This proved to be a turning point in Libyan history as it encouraged the people to not only voice their concerns, but to do something about it. Shortly afterwards, in October 1981, Magarief founded the opposition organisation the National Front for the Salvation of Libya (NFSL), together with several other likeminded dissidents, and he continued to work democracy in Libya for 31 years whilst living in exile.

The NFSL, which in May 2012 became the National Front party of which Magarief is also the head, stood on a simple twin platform: the removal of Qaddafi from power and the establishment of a democratic Libyan state.

The journey from being the most wanted man by a regime to the head of the Libyan congress took 32 long years and involved a great number of risks.

From 1971-2, Magarief served as the vice-dean of the University of Tripoli, during which time he never hid his discontent with the regime. Speaking about his time at the university, Magaraif recalls sharing his views on the responsibility of the state with his students.

“After close observations I realised that the regime was going against the aspirations of the people. I never said anything against the regime but never hid my feelings and the discourse between me and my colleagues was clear to the students.”

The first time Magarief felt the regime was going too far to protect itself was the time when he visited the prisons in Tripoli to see old friends.

“I arranged through a cousin, who was a minister and also a member of the RCC (revolutionary command committee), to visit the prisons in Tripoli. I remember how angry I felt at the condition of the prisoners”, he adds emotionally.

“I told my cousin, ‘you have the right to protect yourselves from the enemies of the revolution (slogan of Qaddafi’s revolution) but you should know your limits because if you don’t, you’ll turn the lives of people into hell’.”

The reports about torture were emerging in those days but with Magarief’s complaint straight to the higher staff, a committee was formed to look into the allegations of prisoner abuse and torture.

“My cousin responded to my complaints and set up a committee to investigate the matter”, Magarief recalls. “He later paid with his life. He was killed in 1972 in a car accident but we know that he was murdered by the regime.”

Worried that he may have proved dangerous if allowed to continue in the university and have direct interaction with the students, the regime attempted to silence Magarief by promoting him.

“The regime promoted me from the vice-dean of the university to the auditor general of Libya. I knew it was a way to silence me but I kept working in a similar fashion. I worked as the auditor general for five years, from July 1972 to November 1977. I did my job properly; wrote reports about the irregularities, massive corruption and embezzlement of funds that was clearly taken place; and openly criticised the RCC.”

The auditing reports by Magaraif were “very well received” by the RCC and according to him the report he wrote for the year 1974 was behind a serious coup d’état attempt by RCC officers.

The auditor general in the 1970s reported directly to the RCC and Magarief met Qaddafi many times because of the work did.“Once he (Qaddafi) wrote on the report, in front of me, that a third party should be formed to look into the findings of the report but I knew that nothing would happen and indeed nothing did.”

Despite the regime’s efforts to silence him or to force him to stop highlighting the issues, Magarief continued to work in the same way until the regime could no longer tolerate it.

So it was that Magaraif was appointed as the ambassador to India in 1977. He knew that it was yet another attempt by the regime to get rid of him. “I asked the officer in charge : ‘why are you not sending me back to the university, I came from there?’ But he had no answer and I told him that I know the reason behind it and you don’t have to tell me.”

During his time as ambassador he kept busy in charity works while the situation back in Libya was deteriorating and the murder of dissidents became more and more commonplace, including public hangings of students by the Qaddafi regime. All the dissidents were being tracked down. When found they were either put in indefinite detention, often in terrible conditions, or killed on the spot.

It was not until February 1980 when Magarief was recalled for official meetings that he knew the same fate could now befall him. During his stay in the country, Qaddafi started killing political prisoners whilst they were in jail and this was the moment when Magaraif decided that he had to do something.

“I made up mind and went to seek the blessings of my father. I just told him that I’ll take a stand without giving any details. I arranged for my son to join me in India and left the country.”

Qaddafi agents assassinated 11 Libyan dissidents in Europe in broad daylight during the months he was waiting for his son. It only added to his determination and soon after the arrival of his son to India, Magaraif decided to go to Morocco for a holiday with his family. It was there, on 31 July 1980, that he announced not only that he was resigning his position as ambassador, but also that he was severing ties with the Qaddafi regime, which he said did not represent the Libyan people.

At this point there was no plan, no support and no organised opposition. Magarief had only planned up to that fateful press conference Morocco, and he made his decisions for the future based on the reactions of both the regime and the Libyan people to his statement.

The regime didn’t take long to react and imprisoned his siblings after demolishing his house. Magarief himself was then sentenced to death by a military court in absentia. It wasn’t long after that the first attempt on his life was made, on 23 April 1981.

“The NFSL was not formed yet and neither was I involved in any activities against the regime at that time of the first of many attempts on my life”, Magarief says. “It was just to show how somebody could even think of such a thing. It was surprising for Qaddafi.”

Magarief is not sure, however, whether or not if Qaddafi knew all along of his intentions. “I am not sure if he knew but he definitely had sensed it as he used to tell his colleagues not to listen to me as I’m very persuasive. Abdul Sallam Jalloud, the second man of the regime, visited me in July 1978 in India and said, ‘Mohammed there are many people who don’t like you and many who do, both agree on one thing that whatever you undertake, you complete it.’ And it is correct; I am very focused and determined, I fully devote myself to whatever I’m doing.”

After the public hangings of the students and the nationalisation of much property in Libya, dissidence against the regime was increasing in Libya. Many people had fled the country following the crackdown but there was no regular opposition. There were student groups that were organising the demonstrations against the regime outside the country but no group was able to rally support around it. Magaraif’s press conference surprised many and people started to contact him to ask what he planned to do next.

After getting together with a few old comrades and some new dissidents he went touring different countries to assess and evaluate the regional system and atmosphere. It was then that they formed the NFSL and wrote the two point agenda of the group that was to get rid of Gaddafi and to establish a country with democratic institutions.

The manifesto of the NFSL also authorised the use of force against the regime. “Qaddafi came through force and by that time he had made it clear that he wouldn’t go easily, thus, we gave ourselves the option of using force against him straightaway.”

The dissidence was growing and people were waiting for a direction. After the formation of the NFSL, people joined in large numbers. “People connected with the message and within months we had many members”, Magarief recalls.

It was months later that the military wing of the NFSL tried the famous Bab-el-Aziziyah assassination attempt. The plan was thwarted as the commander of the group was captured on the border trying to enter Libya. The other members were either killed in action or imprisoned, only to be killed later.

The national assembly (internal body of the organisation) of the NFSL chose him as the secretary general in May 1982, a position he held until 2001 when he resigned voluntarily. As the secretary general, he travelled around the world to gather support against Qaddafi, gave speeches in different countries and tried to unite the opposition groups. There were many attempts on his life and he was the number one wanted man by the regime.

“I was told by many people and also the documents found in the intelligence offices confirm that Qaddafi paid a lot of money to the mafia to get to me”, Magarief says.

Magarief survived many attempts on his life. Most famous is the one when a UTA airliner was downed by Qaddafi agents following reports that he would be present on the flight. “I was booked on that flight but I changed my mind and left two days earlier to attend the wedding of my daughter. It was the will of the Almighty that I survived all those attempts.”

Even after his resignation as secretary general, remained actively involved in the NFSL and was part of every decision taken by the organisation. He wrote several books on the contemporary history of Libya and the way Qaddafi dismantled the state. He was working on the books when talk of the revolution started and he issued his statement the week before the first demonstration, encouraging the people to come out on the street to demand their rights.

In May 2012, seven months after the liberation of Libya, the NFSL was dissolved and reformed into a political party, the National Front. Magarief was elected as the head of this newly formed political party that participated in the first elections of the free Libya in July 2012. He also won a seat in the Congress and was voted in as speaker of the Congress on 9 August 2012.

The journey from being the most hunted man by the Qaddafi regime to the head of the Libyan Congress also affected Magarief’s personal life. His family was made to relocate several times following constant threats to their lives. Magarief’s daughter Asma recalls living in constant fear of being spied on, but feeling proud of her fathers’ work. “Because of his line of work, we had to relocate a lot and lose our friends in the process but we knew that he was working for the country and we always felt proud.”

According to Magarief, he was able to do all the work because he always believed in the justness of the cause: “My colleagues gave their lives to the cause, and how could I forget all that?” He was appreciative of the support he received from his family over the years, “I was supported by my family; they always believed in what I was doing.

“How else would you expect history to be changed, but through sacrifice?”

Umar Khan can be found on Twitter at www.twitter.com/umarnkhan [/restrict]