Mustafa J. Salem.

Tripoli, June 2014:

![Almost identical volcanic cones in central al Haruj Al-Aswad. Typical radial drainage pattern signifies the uniformity of cone shape. Sediments of fine sand and silt of fluvio-aeolean origin are in white in the centre of the . . .[restrict]cone.](http://www.libyaherald.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/volanoes.jpg)

Al-Haruj Al-Aswad or the Black Haruj and Al-Haruj Al-Abyad (the White Haruj) represent the largest volcanic field in Libya. Covering an area of over 40,000 square kilomeres in central Libya (Figure 2), it is not only an interesting area for volcanologists, geologists and adventure travellers but also – and has been since time immemorial – a valuable territory for people living in the nearby oases, such as Zallah, Hun, Soknah, Waddan (all in the Jufrah area), Al-Fugaha and even as far as Temessah in the southwest. When it rains in Haruj, hundreds of people from these oases head to the various areas of the vast volcanic field to enjoy their sudden greening and check the water courses which they call Queltas, which result from the rainfall. Many of them hunt game such as rare gazelles, and waddan. Areas with enough rain will be visited regularly and livestock, mainly camels, will be moved there for grazing.

Al Haruj is not only a recreational and grazing area for the inhabitants of the oases, it also contains some important hydrocarbons. The eastern and northern edges of Al-Haruj have been producing oil for several years. The latest discoveries in the area is An-Naqah Field in east Haruj (Figure 3; A and B).

When these important oil resources were explored and discovered, there was some environmental impact on the surface terrain as well as on the rare faunas and floras. There was bulldozer cleareance for the purpose of seismic activities that preceded the oil discovery and also civil works associated with the development of the oil field.

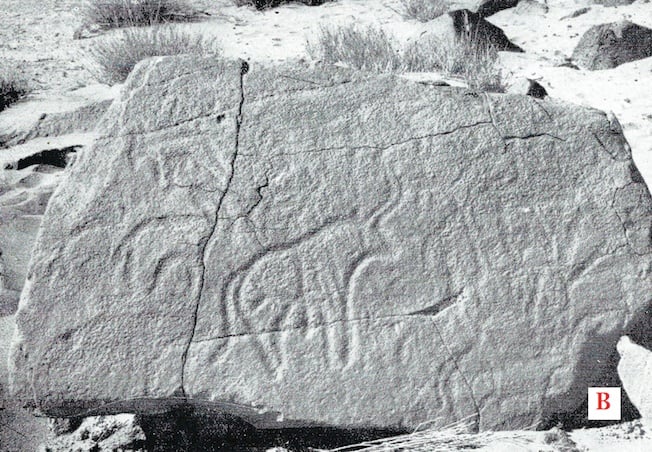

Historically, Haruj, like the other areas of the Libyan desert, was inhabited in prehistoric time. Prehistoric tools and lithics were reported from several sites within the entire area. Prehistoric artworks represented by wild and domesticated animal engravings are present in some wadis, such as Wadi al Had as well as in the northern edge of the volcanic field near the Oasis of Zallah (Figure 4, A and B). Most of these sites need detailed studies by the archaeologists.

Physiography of Al-Haruj area

The Haruj volcanic field rises out of the surrounding Sarir gravel plains. The relief (height) of the area in the northern Al-Haruj Al-Aswad is averaged at 700 metres above sea level (MASL), with some higher volcanic cones and shield volcanoes. In the southern Haruj Al-Abyad, the relief is averaged at about 550-600 MASL, one area in the latter, Qarart at Twaylah, is about 1,200 MASL.

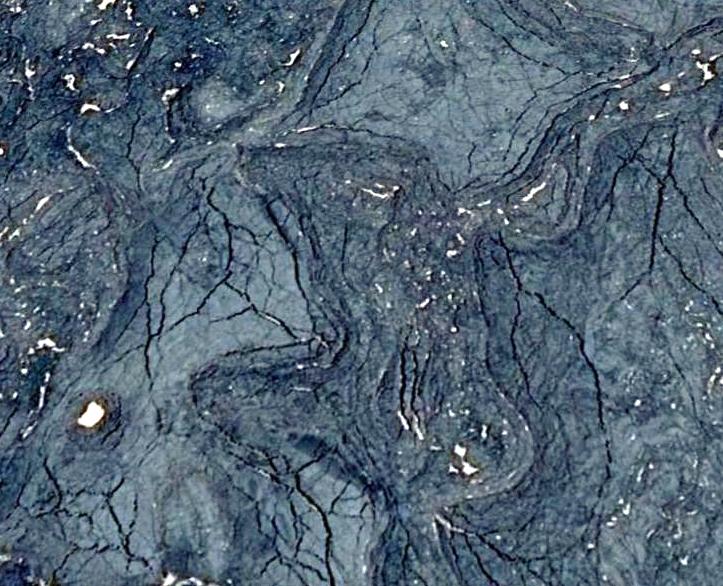

The landscape of Al-Haruj is characterised by hilly, undulating or hummocky morphology, with frequent steep lava fronts, pressure ridges or blocky lava fields.

Al-Haruj is cut by several wadis which have dendritic drainage patterns. These wadis radiate from the main volcanic complex to various directions. Typical to Al-Haruj topography are the numerous small depressions within the lava fields (locally called balta) which are flat-bottomed, ranging in size from a few hundreds metres to a few kilometres in diameter. These baltas are bordered by lava flows and filled by argillaceous, Aeolian and fluvial sediments of mostly silt and fine sand. After rainfall, shrubs and seasonal grass grow in these depressions and wadis which attracts various animals. (Figures 5 and 6).

The northern part of Al-Haruj Al-Aswad is characterised by lavas with ridges, cracks and collapsed lava, which is locally called Al-Msheqqaq.

For decades, the whole area of Al Haruj has been almost uninhabited. There is only one familywho live permanently in the area, the Al-Fakhri. They are in the eastern part of Al Haruj, with their animals. Since the oil industry moved in to the area after the Naqah field was discovered and developed), the Fakhri have had access to precious fresh water which used to be trucked from far away.

It is suggested that rainfall in Al-Haruj ranges between 15 and 30 millimetres a year. However, some oil workers believe that it may be more in some parts of the volcanic field.

The main flora found in the area are: Acacia tortilles, Ziziphus lotus. Some annual plants and grasses grow after rainfall in wadis and baltas. (Figures 5 and 6).

Structure and composition

The Jebel Al-Haruj is part of an alkaline basaltic intra-continental flood basalt field in central Libya,withvery well-preserved basaltic fields containing scoria cones, lava flows and explosion craters.

Basalt and related rocks occur as Tertiary-Quaternary lava flows ranging in its age from about six millon to just under half a million years old, covering an area exceeding 40,000 square kilometres.

Ulrike Martin and Karoly Nemeth in their article in the 2006 Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research on Al-Haruj indicate that at least four types of scoria cones have been distinguished, in this area.

According to M.T. Busrewil and Swesi (1993), the vast areas of Al-Haruj basalts consist of six lava flow phases of varying thicknesses, extensions and dating. Their eruption is generally controlled by the larger Afro-Arabian NW-SE rift system (Figures 1 and 7). The flow phases range from olivine rich and/or olivine dolerites to olivine and/or normal basalts that consist mainly of variable olivine, clinopyroxene, plagioclase and glass.

The youngest lava flows of the Haruj field were considered by Eberhard Klitzsch writing in 1968 to be Holocene in age and are located at the northern side of the field, near the oasis of Al Fugaha (Figure 8). A significant series of volcanoes that are called Q?rat al-Saba rise up to about 1,200 MASL. Ancient lava streams run in all directions, with grass, bushes and some acacia trees. In the southern Al-Haruj Al-Abyad, a series of volcanoes are called Unq?d Al-Y?sir?t. Two lines of about 40 volcanoes appear.

Prospects for Development

Like all other interesting sites in the Libyan Sahara, Al-Haruj Volcanic Field with all its diversified terrain, dozens of interesting volcanoes and historical significance should be considered as an area with good prospects for development – and protection – for the serious visitor. The central area of the Qur as Sabaa volcanic field could be a good area for visitors interested in volcanoes their structure, type and composition, climbing and adventure. The whole area of Al Haruj could be developed as a “Geopark” with the main emphasis on the various volcanoes, their morphological and geological interest. Some emphasis should be put on sites with prehistoric engravings. Though this area may not be a priority in protection and preservation it should be studied and nationally listed as one of the areas to be protected in the near future (Figures 4 and 8, A and B).

It should be emphasized, however, that any protection or preservation programmes have to take in consideration the needs of the local communities surrounding Al-Haruj and Jabal Al-Sawda. For these people, Al Haruj is their back yard, their animals graze in it and they use it for recreation, hunting and the like. Therefore the area can never be off-limit to them and their animals.

The oases of Al-Fugaha with its small historic town, traditional agriculture and near to the volcanic fields, could be a good supply base and with accommodation for visitors to northern and central Al Haruj either as interested tourists or members of scientific expeditions. Zallah oasis, on the other hand, will be a good base for visitors of north and north-east Haruj. For visitors interested in the southern part, Al Haruj Al-Abyad, and Waw An-Namus, the government farm and guest house at Waw Al-Kabir could be used as a station for accommodation and water supply.

[/restrict]