By Nafissa Assed

We have all heard that . . .[restrict]a picture is worth more than a thousand words. On Saturday, 31 March, London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, in collaboration with the British Council, organized the opening of Street Art in Tripoli, Libya. The exhibition is in Dar Al-Fagi Hassan Art Gallery in the old medina – city – of Tripoli. The exhibition featured many pictures and painted graffiti by talented Libyans. It shows that painted graffiti has developed into a rich and democratic visual expression that is commonly called “street art.” It has taken various shapes and turned out to not only painted graffiti on the walls but also a medium that creates distinctive and exciting images along the way. The exhibition explores the language of the Libyan street during the uprising. Through their graffiti, Libyans fully expressed what liberation really meant to them. Painting on the walls of Libyan cities and showing the works of astonishingly talented Libyan youth who no longer had to fear death or torture showed the depth of most Libyans’ feelings.

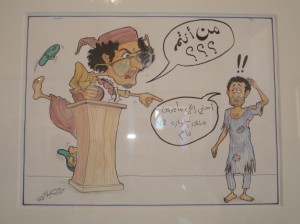

Street art is art, explicitly images, created in public spaces – that is, “in the streets” though the term often refers to ‘’unsanctioned’’ art. The term can also include traditional graffiti artwork. I have been fascinated by much of the street art and graffiti that has sprung up all over Libya showcasing some brilliant artists as well as the Libyans’ ironic sense of humor. In fact, throughout the Arab Spring, Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen and Syria have chanted ‘Irhal’ which means “Go” or “Leave” whilst the Libyans have chanted “Jainag” which means “We are coming to get you” as well as “Man antom?” (This last was the notorious question that Gaddafi addressed to his people in one of his most frightening speeches in February 2011; it means “Who are you?”.)

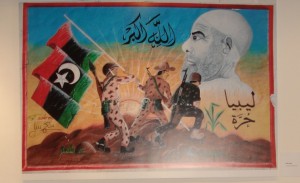

Libyans are finally free to express themselves! Many of the painted graffiti, as well as the written words are in English, Arabic and sometimes in the Berber language, Tamazight. Libyan urban art is characterized by the imaginative use of the colors of the previous national flag as a design element. That is the flag from the time of King Idris in which red, black and green dominate and are in abundance in every corner of Libya, used in different outlines and forms. A lot of the artwork, particularly in Tripoli, also makes reference to Omar al Muhktar, the freedom fighter who led a fierce resistance against the Italians in the 1920s.

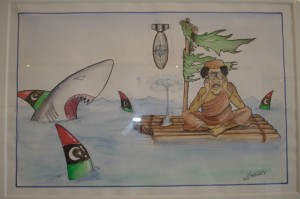

Street art has its roots in political commentary, from propaganda and protest posters to spray-painted slogans. Basically, political graffiti relies on prominent locations and strikingly phrased comments on current situations and environmental issues. At the same time, street art relies less on words and more on figurative and metaphorical imagery. That is evident in the mocking drawings and narratives of Libya’s vibrantly expressive street art.

Although the art in Libya is tied to a specific location, they are put out to a world-wide audience via online galleries and blogs which spread the message. Street art in Libya has also gained an international reputation and status since the Arab Spring, including a 2012 exhibition in Madrid’s Casa Árabe.

Sketching and painting in Libya in this way has given a voice to truth. And with this sense of public exposure has come exuberance. As a medium, street art has always been original and engaging, immediate and democratic. Libyan revolutionary artists have released what is inside their hearts by taking their aversion toward Muammar Qaddafi to an especially visible level, creating street caricatures that ridicule the former leader and his notorious inhumanity. For example, when you see the walls in Libyan streets, you will figure out that “the brother leader” is no longer a leader, or even a colonel, but has been fully dehumanized as a rat, a chicken, a snake, a devil, a cowering child or a Nazi.

The exhibition offered a look at a vibrant genre that continues to evolve and establish itself as an art form in its own right. To the V&A (Victoria & Albert Museum), the British Council and the Ministry of Culture and Civil Society, who gave their time and expertise to this brilliant exhibition, I offer my sincere thanks, admiration, and appreciation for their enthusiastic support of Libyan street art.

The exhibition is open everyday from 10:00 – 2:00pm and 4:00pm – 8:00pm.

It is open to the public and admissions free of charge. We look forward to your attendance! [/restrict]